Visitors familiar with the august halls of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge will find that things have changed. Where has Titian’s savage Tarquin and Lucretia gone? Other Old Masters are jostling for attention in the face of the provocative intrusion of works by David Hockney. Meindert Hobbema’s much-loved masterpiece, The Avenue at Middelharnis (1689) borrowed from the National Gallery, has been given a drastic make-over by Hockney.

The context is the first exhibition of his art that concentrates on his radical ideas about seeing, perception and representation. This seemed like a suitable theme for a great university when I proposed it to the Heong Gallery in the University of Cambridge’s Downing College, from where it was to be taken up with transformative power by the mighty Fitzwilliam.

The Avenue at Middelharnis (1689) by Meindert Hobbema

Photo: National Gallery, London

From the beginning, Hockney was ploughing his own furrow as a painter of the seen world, consciously operating both within and against the great tradition of naturalistic art, at a time when Abstract Expressionism ruled the roost. The earliest work, in the Heong, is a metre-high study of a skeleton made at the age of 22 at the Royal College of Art. The position of the drawing in the long tradition of academic teaching is evident, for all its preciously personal draftsmanship. It was bought by fellow artist, R.B. Kitaj, who had “never seen such a beautiful drawing”.

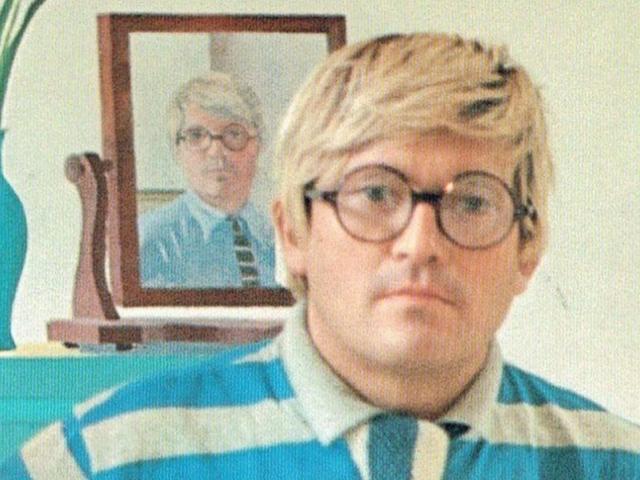

It is Hockney’s paradoxical form of anarchic traditionalism that lies behind the exhibition’s juxtaposition of Hockney’s portraits with assertive likenesses by Joshua Reynolds and William Hogarth. Hockney’s skittish iPad drawings of flowers dazzle in one of the greatest of all galleries of flower paintings. Claude Monet’s light-filled canvases and Hockney’s serial images of Normandy in blossom reinforce each other’s radiant presence.

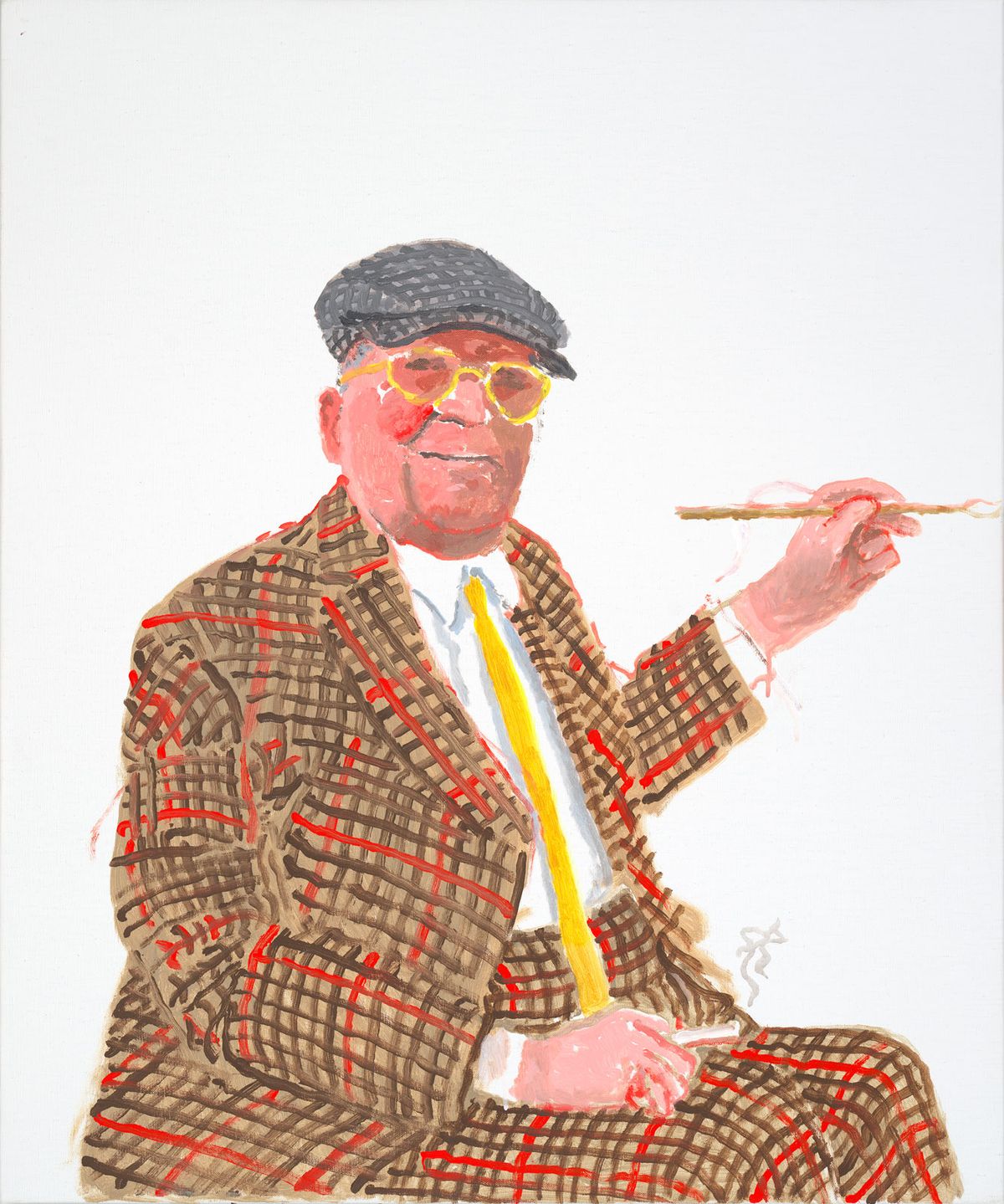

David Hockney's After Hobbema (Useful Knowledge) (2017) is based on Hobbema’s 17th century painting The Avenue at Middelharnis © David Hockney

Underpinning our enterprise is his 2001 book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, in which he argues that European art for four centuries was dominated by a “camera culture” in which the spectator is constrained to act as a “one-eyed cyclops”. The optics of linear perspective had merged with images made using camera obscuras and concave mirrors. “Where is the evidence?”, I asked him. “The pictures are the evidence”, Hockney replied.

His quest involves more than just looking at paintings. He restlessly experiments with the optical tools available to artists, both as part of his research and to achieve his own individual ends, above all in his 12 Portraits After Ingres In a Uniform Style (1999-2000), large coloured drawings of warders in the National Gallery made using a 19th-century device, the camera lucida. Set in an octagonal room, the uniformed warders observe us disconcertingly. The series sprang from his observation of portrait drawings by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, which he became convinced utilised the camera lucida.

Hockney's 12 Portraits after Ingres in a Uniform Style (1999-2000) © David Hockney

Some surprising juxtapositions work best, most notably when Poussin’s Extreme Unction (around 1637-42)—exhibited with a reconstruction of the stage-like box the artist used to articulate forms and light in space—is compared to Hockney’s recent “digital drawings” of large interiors within which objects and figures are manoeuvred like pieces on a chessboard.

Hockney’s escalating rejection of linear perspective climaxes in his exploration of “reverse perspective”, which draws inspiration from Pavel Florensky (1882-1937). The Russian theologian and theorist claimed that the non-optical rendering of form and space in traditional Russian icons was retrospectively validated by Cubism and modern physics.

Where do I as a historian stand in all this? Even when I think he is wrong, most notably in claiming that icons are about seeing “real space” rather than spiritual realms in which optical rules are inapplicable, he unfailingly stimulates. I also think that cameras were directly used less extensively than Hockney believes, while agreeing that a pervasive “photographic” mode existed before the inventions by Henry Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre. I discovered years ago that no companion is more compellingly perceptive than Hockney on a tour of an art gallery. Above all I take sustained delight in his insatiable quest to refresh how we use our eyes as dynamic agencies in space and time.

But where has the Titian gone? That is a good question.

• Hockney’s Eye: the Art and Technology of Depiction, Heong Gallery and Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, until 29 August

• Martin Kemp is an art historian and emeritus professor of art history at the University of Oxford