At 5am on 24 February, the Kharkiv-based artist Olia Fedorova got a call from her mother informing her that Russia had launched missile strikes against Ukraine. By then, she had an emergency bag ready to go, which her boyfriend had prepared after Russia had begun amassing troops near its border with Ukraine last year. However, Fedorova says that “people still couldn’t believe that Putin would give an order to invade”.

When Fedorova left her apartment in the city’s old town that morning, queues had already formed for supermarkets, pharmacies, and cash machines. After stocking up on necessities, the next priority was locating the closest thing to a bomb-proof shelter. This came in the form of an abandoned pawnshop under Fedorova’s building. “Our neighbours decided to break the lock and open it for everyone to hide,” she tells The Art Newspaper. “We brought old sofa cushions, furniture, warm clothes and blankets, dishes, food, cigarettes, and made improvised beds. Luckily there is electricity here, so we took down extension cables and lamps.”

“After a long day of working to make our basement safe, we brought two bottles of wine leftover from my birthday to toast to our soldiers, our warriors,” says Olia Fedorova, pictured here second from left

The conceptual and multidisciplinary artist also brought one of her works of art to decorate the shelter. The road sign emblazoned with “Welcome to the Motherland” in Ukrainian was from her project called Off-road Signs. In 2021, Fedorova had travelled across the country installing traffic signs, printed with the words such as “Nothing” or “End”, in secluded landscapes to give these spaces a new meaning.

She did not think her sign would become a symbol of defiance in her country’s stark fight against Russia. “As civilians we don’t really have many opportunities to protect ourselves. We have knives, a machete, and a stick with nails that our neighbour had made. [But] our protection is predominantly fortification—we barricaded every vulnerable place in the building.”

Fedorova has decorated her bunker in Kharkiv with a work from her Off-Road Signs (2021) series that reads “Welcome to the Motherland”

On 24 February, the photographer Artem Humilevskiy was in Kyiv, with plans to visit a photography exhibition in Ivano-Frankivsk the next day. When news of bombs broke at 5am, Humilevskiy packed up his things and drove 500km to his relatives, where he has since been sheltering with his wife, mother-in-law and 8-year-old son.

“We prepared the basement, fortified [the] gate with wooden planks, and loaded an old shotgun with bullets. We all sleep in the safest room (in our opinion), where we taped up the window and stuffed them with pillows. Every day there are air raids.” says the artist, best known for his staged self-portraits creating during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown. “I am trying to keep calm,” he adds.

Since the war broke out, Ukrainians have been collecting empty bottles and old cloth to make Molotov cocktails to defend themselves. Another crucial weapon for Ukrainian artists has been their phones. Humilevskiy is busier than ever selling his photographs as NFTs on his Twitter page, one of which shows Humilevskiy nude in a field of yellow flowers, the composition symbolising the Ukrainian flag. He says he relies on the platform “to tell the world what is really happening in Ukraine” against the backdrop of an information war. “I have been selling my art and donating this money to the army, to hospitals, or those who have no money at all.”

On 25 February, Fedorova posted “a day in the life of a Kharkiv artist” where she detailed waking up in a basement after three hours of sleep and nipping into her apartment to eat while there was no shelling. That day, she had prepared to meet her mum at the blood donation centre but was forced to return to her basement after hearing explosions and getting an air alert. Together with her boyfriend and neighbours, they opened up two bottles of wine Fedorova had left over from her birthday.

“I had worried that as a civilian and as an artist I don’t have the right skills for war and psychologically I am not ready to use weapons and shoot,” Fedorova says. “But I know now that I can use my networks that I developed while travelling to international residencies to share the situation—how regular people are suffering from this war.”

She is not the only Ukrainian keeping an “artist at war diary”. While the photographer Julia Po and artist Elizaveta Litovka are using social media to share photos from makeshift shelters and underground bunkers, Kyiv-based photographer and writer Yevgenia Belorusets, has been posting her daily reports online through Isolarii, a pocket-book publisher, as well as on the Artforum website. On the second day of the invasion, she wrote: “I am struggling with myself. I know slowly the world is waking up and starting to see that it’s not just about Kyiv and Ukraine after all. It’s about every house, every door, it’s about every life in Europe that is threatened as of today.”

Some artists have resumed their creative pursuits, irrespective of the danger and uncertainty of war. A day before the invasion, the Kyiv-based artist Anastasia Nekypila says she felt a sudden urge to sketch the feeling of home, so that evening she made a digital drawing showing a house against a blue sky, a picket fence, and sunflowers blooming in the garden. “There was a rumour that Russia would attack Ukraine on the 16 February. From that day on, we were all anticipating the worst, but only until the last moment did we think it would actually happen,” Nekypila says.

Nekypila posted her drawing on Instagram on 24 February and did not post another illustration until 6 March, showing windows taped against explosions. “That first night I could not sleep,” she says, speaking from Poland, where she previously studied and has fled to with her family. “When I closed my eyes, all I could imagine was sirens, tanks, planes and bombs. My body was preparing to run. I couldn’t work out how this could have happened in the 21st century, how someone could attack my home, what I could do to protect my family.”

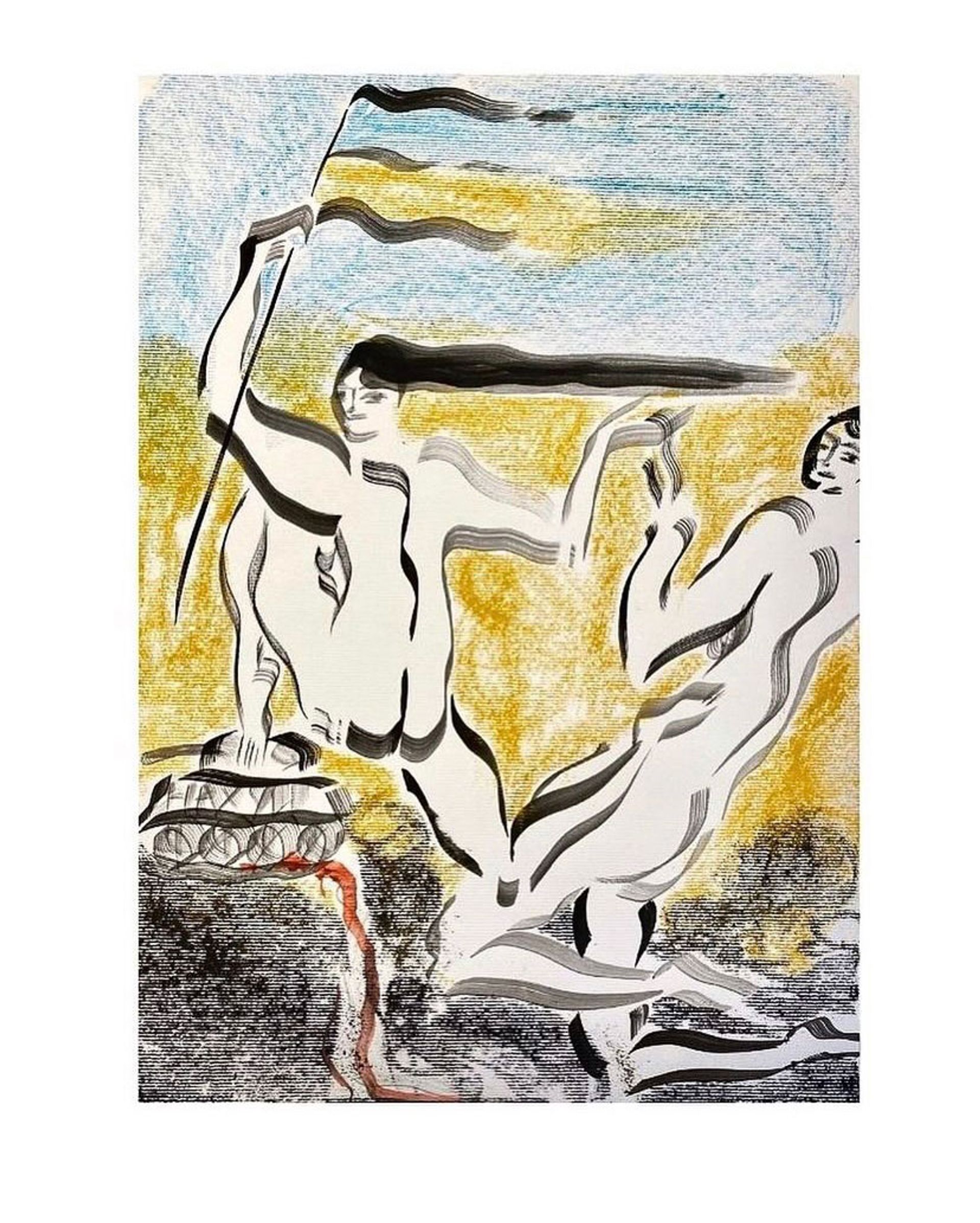

Kherson Heroes (2022) by Sana Shahmuradova

The painter Sana Shahmuradova, who left Kyiv to shelter with her grandmother in the countryside, says she had had to adapt her painting technique, swapping oils for her brother’s crayons and drawing on the back of old wallpaper. One drawing of a woman vanquishing the enemy (symbolised by a snake) was made with leftovers from dinner. “I was sharing the table with my grandmother, who was peeling boiled beet while I was drawing with charcoal,” she says. Some of Shahmuradova’s drawings are poster-like calls to action. For instance, asking the world to “close the sky” over Ukraine to stop Russia’s aerial attacks. “One of the positive drawings was inspired by a civilian from [Russian-occupied] Kherson who jumped on a Russian tank with a Ukrainian flag,” Shahmuradova says. On 5 March, thousands of Ukrainians protested against the occupation in Kherson’s Svobody Square. “I admire the bravery of everyday people in Kherson, who are defending their city without any help,” Shahmuradova adds.

The city of Kharkiv, where Fedorova is sheltering, has been heavily bombed since war began. The night that missiles devastated major landmarks including Freedom Square and the city’s opera and ballet theatre, the artist shared a video of a Ukrainian music concert in her bunker. “I want to show that we are brave, that we keep our spirits, that we don’t give up and don’t lose hope in any case. We are not afraid of Putin and we are all ready to die to stop him taking a single piece of our land.”