Being an artist, by trade, luck or education, basically defines one as an outsider, someone who goes against the grain, who favours passion over practicality. But in the art world there is a defining line. Those who studied painting or sculpture at prestige universities often get the recognition, the shows, the sales. Those who did not have trouble even getting their work seen. The Outsider Art Fair, now celebrating its 30th year with its latest New York edition (until 6 March), has done more than its share of changing that dynamic.

And yet, outsiders were not always the overlooked, the under-appreciated. In the 1960s, a time of monumental change in nearly every corner of the world, outsiders were oracles. They were royalty. From The Beatles to Isaac Asimov to Robert Indiana, artists across every genre embraced psychedelia (often with the help of a tab or two of lysergic acid diethylamide) and thrust it in into the mainstream.

Outsider art at its most simple is work made by a self-taught artist. Psychedelic art, while not necessarily the same thing, is built from the same spiritual and artistic DNA that predates the academy, artists who found their inspiration by locking into their beginner’s mind through a psychedelic experience. They are different practices with large areas in common. Field Trip: Psychedelic Solution, 1986-1995, a special exhibition in the 2022 edition of the Outsider Art Fair’s "Curated Spaces" programme, curated by artist Fred Tomaselli (many of whose works could fairly be described as psychedelic), speaks to the relevance and influence of psychedelia in art.

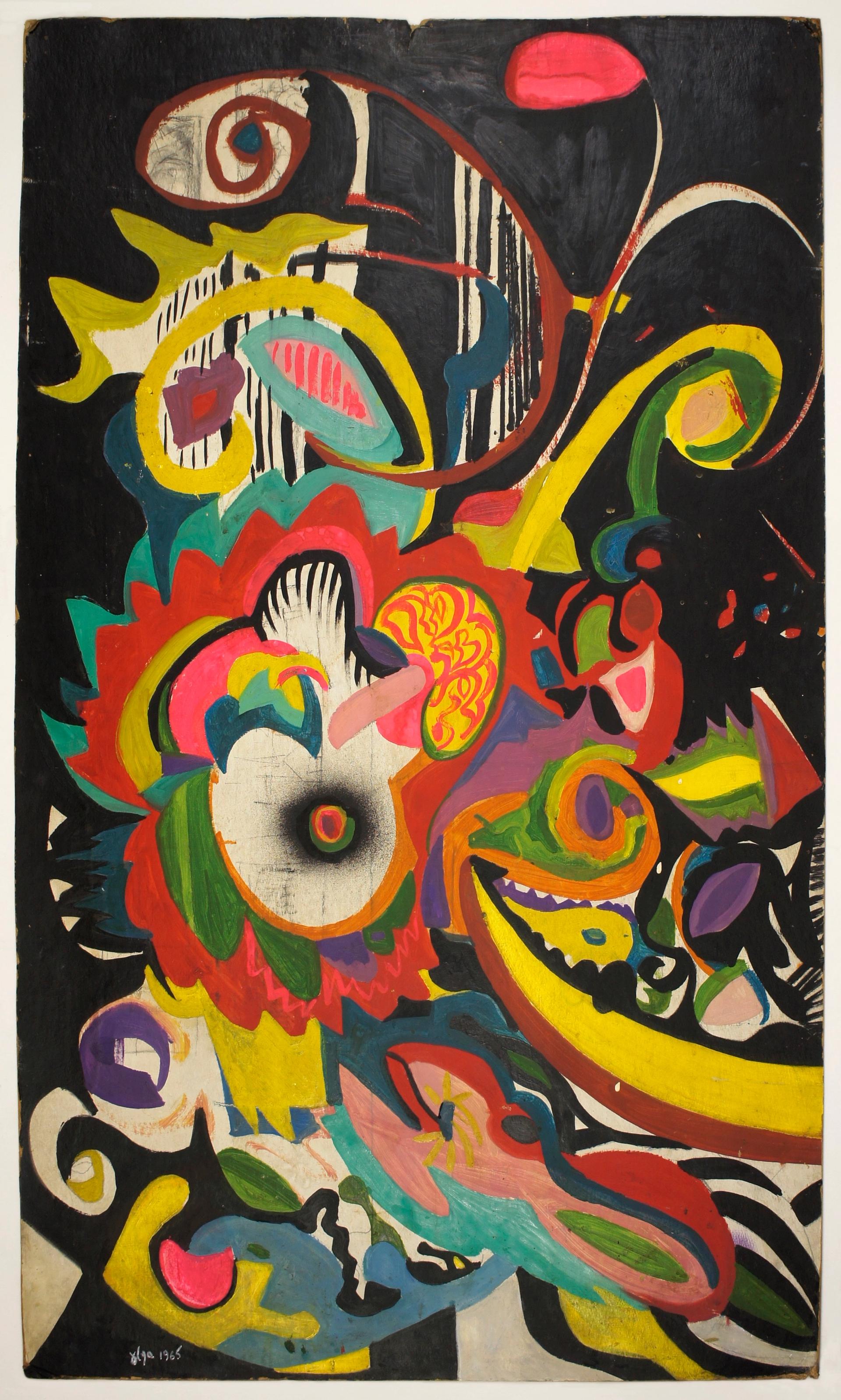

Olga Spiegel, Untitled (1971) Collection of Jacaeber Kastor

Like traditional outsider art, psychedelic art has seldom been included in the official canon of fine art. Field Trip shines when it is thought of as an encyclopaedia. Curated Tomaselli primarily from the collection of Jacaeber Kastor, founder of the underground Greenwich Village gallery Psychedelic Solution.

“Art is a great language to express, investigate and work with elements that are not too easily handled intellectually,” Kastor says. “There’s a concept in outsider art that training can, in a way, spoil something. Psychedelic art shares the freshness that outsider art speaks to, but often the artists come to that freshness through a psychedelic experience.”

The most familiar works are those with a direct link to the 1960s music scene that grew with the psychedelic movement: a drum head by the musician Grace Slick before she joined Jefferson Airplane, the Edmund J. Sullivan illustration of a skeleton surrounded by roses from an illustrated copy of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam that inspired the Grateful Dead’s logo. But the real treasures are works that reflect the full breadth of the 1960s counterculture.

“Normally outsider art deals with people that are very individuated, that are locked into their own worlds,” Tomaselli says. “This show describes a subculture that’s outside of the mainstream, like outsider artists, but connected to one another through a sensibility they share and a social sphere.”

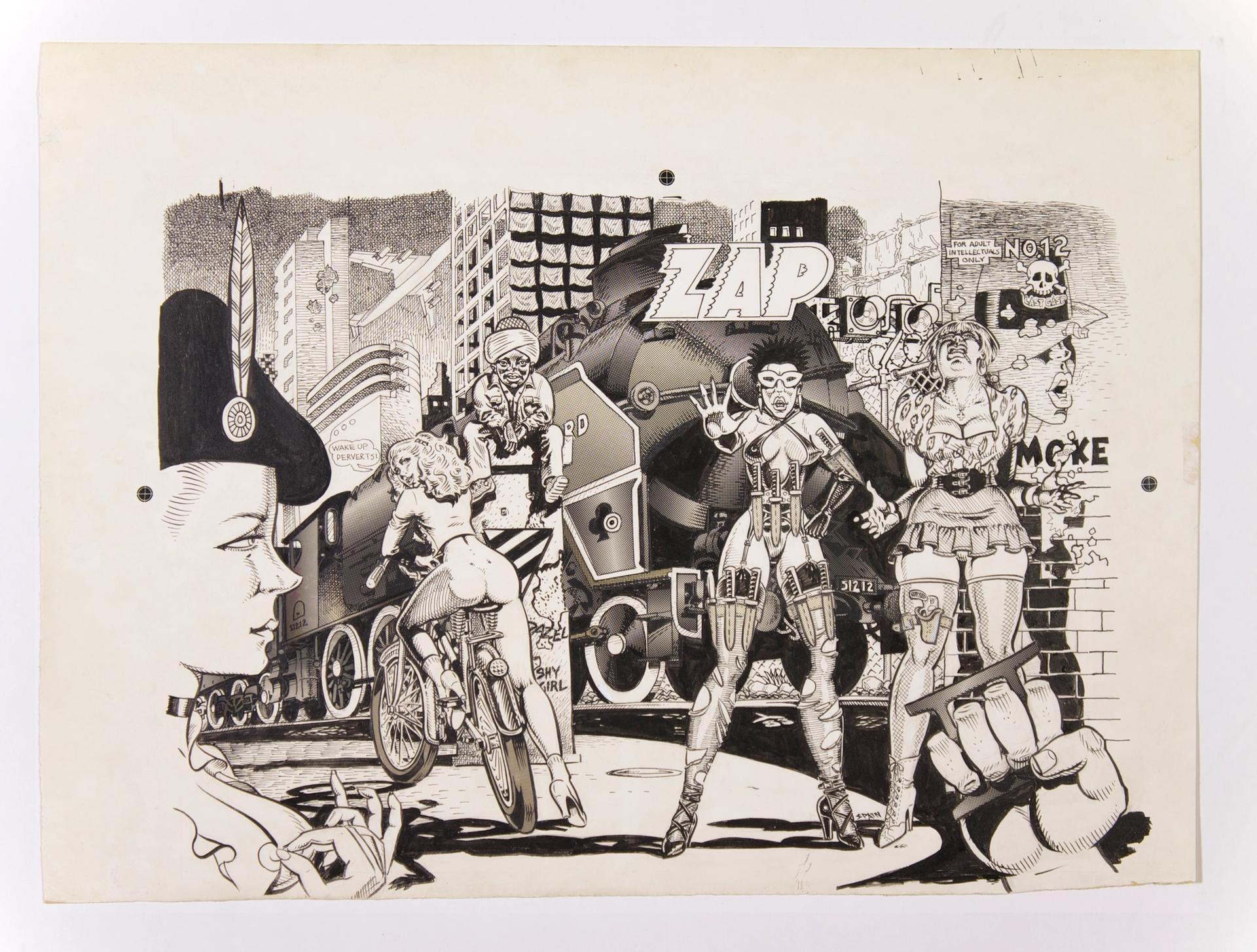

Spain Rodriguez, Zap No. 12 (1989) Collection of Jacaeber Kastor

Isaac Abrams, Olga Spiegel and Robert Crumb all owe something to the psychedelic movement, and in turn have inspired many visual artists who are working on the inside of the art world. Much like the outsider art works that your average museum-goer might dismiss, there are examples in Field Trip of true masters in their craft. Tomaselli points to the late underground comics artist Spain Rodriguez, whom he describes as “essentially a master draftsman”, and Olga Spiegel, an artist he only discovered while curating the show, whose dynamic, colourful paintings blend elements of the natural world with an otherworldly abstraction.

“It’s sort of an elephant in the room,” Tomaselli says. “There are people I know with very sophisticated painting practices who will talk about the influence of Zap Comics on their work. Whether or not this type of work gathers wider acceptance in the art world, it needs to be acknowledged as an influence in the culture.”

- Outsider Art Fair New York, until 6 March, Metropolitan Pavilion