A Benin bronze-inspired installation by the Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor has been installed beside a plaque in St Paul’s Cathedral, London, that commemorates the British admiral who led the 1897 expedition to plunder the African artefacts.

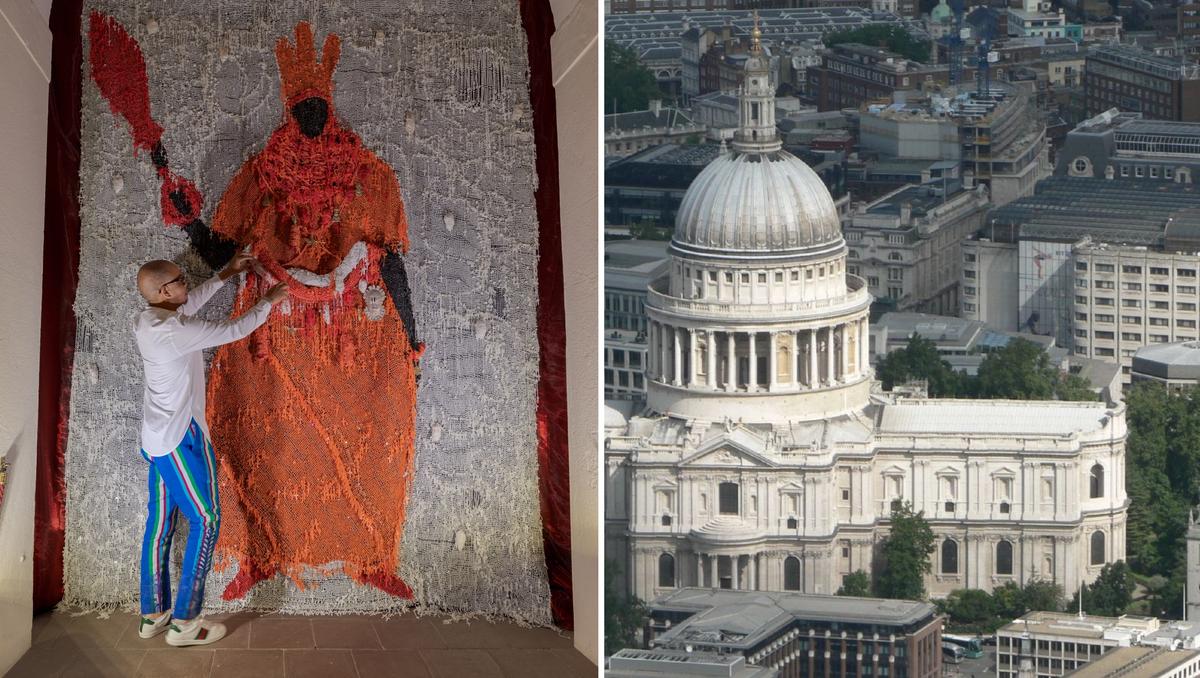

Unveiled to the public today on the 125th anniversary of the British military attack on the Benin Empire, Still Standing (until 14 May) addresses the region’s fraught colonial history by merging references to both Christianity and traditional Edo religions. Measuring 12 ft tall, the textile and metal work is made from 6,000 rosary beads, rhinestones on lace and a number of bronze statuettes cast by Ehikamenor in Benin City (now in modern day Nigeria), which resemble hip ornaments worn by royalty of the Benin Kingdom.

Ehikhamenor says he was spurred to create the work around the time he represented Nigeria at the 2017 Venice Biennale with an installation that featured hundreds of Edo bronze heads and statuettes. The work received pushback from a prospective pavilion landlord who "read the whole thing as fetish, black magic—she was unwilling to have them placed inside a Christian building,” he says. “She was so ignorant about how my culture uniquely presents things as sacred—why can she canonise a rosary bead and at the same time demonise my statue? I wanted to fuse the two together and see what conversations arise.”

More provocatively still, the work presents a direct challenge to the legacy of the admiral Harry Holdsworth Rawson, whose bronze and marble memorial has been installed in the cathedral's crypt since 1913. Rawson was instrumental in not only the punitive expedition in Benin City, but a number of other highly controversial 19th-century military campaigns including the Second Opium War in China.

In questioning this monument and our understanding of Rawson's expedition, Still Standing engages with the thorny and timely debate around the restitution of cultural artefacts—in particular the Benin bronzes.

"History never sleeps nor slumbers. For me to be responding to the memorial brass of Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson is a testament to this," Ehikhamenor says. "There are old coloniser countries and institutions still playing footsies with the issue of restitution, the ground on which they stand should start shaking and shifting."

However, St Paul’s is not trying to make a pointed statement on the issue of repatriation, stresses the cathedral’s chancellor Paula Gooder. Rather, she says that by hosting the work, her institution is “providing a space for conversation around how we should approach monuments in the 21st century”. A panel discussion between Gooder, Ehikhamenor and the cultural restitution expert and author Dan Hicks, who co-commissioned the work, will be held tonight in the cathedral and address this charged topic.

Nevertheless Ehikhamenor, who has long been an outspoken critic of the lack of speed and fervour with which former colonial powers repatriate stolen objects, makes his position clear: "Not to believe in full restitution is for me not believe in full justice," he says. "Any country or kingdom or state asking for what has been looted from their ancestral land should be obliged without long story. We must now shift from 'retain and explain' to what I call 'return and explain.'"

He adds that current conversations around restitution need to evolve to “add contemporary artists to the conversation so it is clear to the world that African artists who started making works post-colonialism didn’t emerge from a vacuum."

The artist says he is now in conversation with Jesus College at the University of Cambridge, the site of a heated debate over the college benefactor Tobias Rustat's connections to slavery, to show his work there.

Ehikhamenor’s work is part of the cultural commissioning series 50 Monuments in 50 Voices, a collaboration between St Paul's and the University of York, which invites creators from comedians and poets to artists to respond to the cathedral's monuments. The initiative is itself part of a wider three-year project, Pantheons: Sculpture at St Paul’s Cathedral, c.1796-1916, launched in autumn 2019, to digitally record the monuments of St Paul’s Cathedral established during the so-called long 19th century.

Gooder says that St Paul’s is now looking at further ways to address its colonial legacy and that she believes faith is a "key way to encourage people to reflect on these conversations".