It is monsoon season in Madagascar. Clouds hang heavy in the sky. Sheets of water glisten on the plains. The season is young, and tornados are scheduled.

Antananarivo, the capital of the world’s oldest island, is a teeming urban sprawl across 12 hills. Its name translates as “the city of a thousand warriors”. Today, grand buildings stand cheek by jowl with improvised shanty homes. More than 35,000 inhabitants are currently living in emergency shelters. Over half of the city’s 2.6 million residents live on flood-prone land, while three-quarters of Madagascar’s citizens live on less than $2 a day. The national football stadium is currently full of Malagasy families who lost their homes to the deluge.

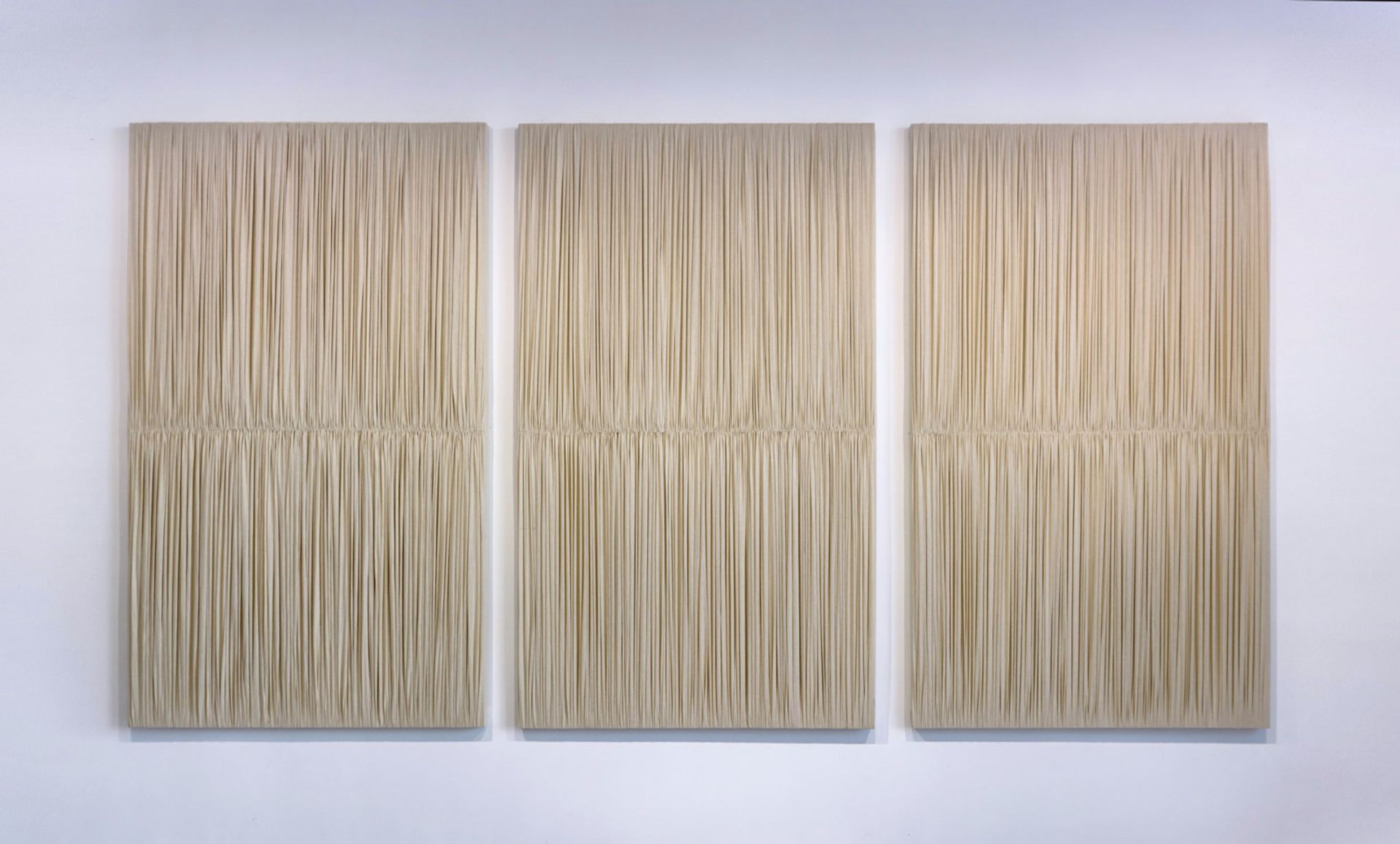

Installation view of ‘Ny Fitiavanay/Our Love/Notre Amour’. Courtesy of the artists and HAKANTO CONTEMPORARY

Into this context comes Hakanto Contemporary, the country’s first contemporary art centre. Its artistic director is Joël Andrianomearisoa, the Antananarivo-born artist who represented Madagascar at the Venice Biennale in 2019, the first time the country had ever participated in the “Olympics of the art world”. He has been based between Paris and Antananarivo for two decades. “I am still in love with this complex city,” Andrianomearisoa says. “I wanted to create a place for artists that inspire me.”

The money behind the venture comes from Hasnaine Yavarhoussen, a 35-year-old art collector and the chief executive of Groupe Filatex, a real estate and energy firm that provides around a third of the island’s power. The gallery launched in February 2020, just weeks ahead of the pandemic, and is only now beginning to welcome foreign visitors.

The opening represents a major event for the artists who live and work in Antananarivo. Hakanto Contemporary provides them with the opportunity to communicate the unique cultural character of Madagascar—one that is born out of multiple colonial histories yet remains obscure to most Westerners. Andrianomearisoa notes that many tend to associate the country with the animated animal film of the same name. “There are people here, too,” he says.

Rakotoarivony’s portrait of a woman is at the centre of the

Ny Fitiavanay exhibition Courtesy of Viviane Rakotoarivony and Hakanto Contemporary

The current exhibition, called Ny Fitiavanay (our love), runs until 16 March. It brings together pieces by 26 Malagasy artists working across sculpture, creative salvage, painting, photography, video, sound and light installation. This show is the first time many of the artists have ever exhibited their work to a museum standard.

Powerful presence

But an upsetting turn of events at the opening of Ny Fitiavanay captures the challenges Hakanto Contemporary must contend with as it develops and grows.

At the centre of the exhibition is a beautiful photographic portrait of an ageing Malagasy woman. Almost three metres high, it has a quiet but powerful presence. The image focuses on the care with which the woman presents herself amid poverty that most in the West would find unimaginable. The photographer, Viviane Rakotoarivony, spotted the woman at a local food market. “It’s a simple portrait, but I felt her strength,” she says.

Rakotoarivony situates her photography within the medium’s humanitarian tradition, and often works for the UN. Herself an expectant mother, she has a particular interest in the experiences of the women surviving, and often raising their children, on the city streets.

Installation view of ‘Ny Fitiavanay/Our Love/Notre Amour’. Courtesy of the artists and HAKANTO CONTEMPORARY

As Andrianomearisoa planned the exhibition, he decided to paste Rakotoarivony’s images in monumental form on the streets around Lycée Rabearivelo, a school near the city’s Heller park. Not just confined to Hakanto’s interiors, Ny Fitiavanay was conceived as a public exhibition, accessible to all.

A few days after the show opened, Andrianomearisoa discovered that each of the posters had been torn down by unknown assailants. “We do not understand why they have done this,” he says.

Naina Andriantsitohaina, the mayor, identifies Rakotoarivony’s portrait as his favourite work in the exhibition and describes the attacks as a “tragedy”. “This is the challenge,” he says, noting that he faces opposition to state investment in culture when the demands for basic amenities are so pressing. Clearly, the case for an art centre in Antananarivo is still being made.

We are under the water, but we can dream. Art can do thatJoël Andrianomearisoa, artist and artistic director, Hakanto Contemporary

Also on show is a video by Rijasolo, a Malagasy photographer raised in France. Now he splits his time between press commissions and his personal practice, a monochrome, painterly rendering of Antananarivo street life. Days after the gallery press view, Rijasolo published with Agence France-Presse images that document the aftermath of a disaster nearby. During the heavy rains, a hillside car park collapsed on the improvised houses below. The bodies of four children and one adult were found in the rubble.

A project for everyone

In conversations, Yavarhoussen gives every impression that he is committed to funding Hakanto Contemporary for the long haul and keen to establish Malagasy artists on the world stage. The centre is free to visit and will remain so. There are plans for a larger standalone gallery, an upgrade from the current 400 sq. m site in an office block. Residencies and international travelling exhibitions of Malagasy art are under discussion. An education outreach programme is already under way in schools across the city.

It would be cynical, then, to doubt Yavarhoussen’s sincerity, or Andrianomearisoa’s determination, to make this “a project for everyone”. And the obstacles they face are far from unique on the African continent. Over the past decade, comparable art centres have opened in cities such as Accra, Abidjan, Dakar, Lagos, Luanda and Marrakech. Like Hakanto, they are public-facing but often funded by a private patron and born out of a private collection. Palais de Lomé, which opened in 2019 in a restored colonial-era palace in Togo, is the only major contemporary art venue in Africa to be fully state-financed.

Alexandre Gourçon © Hakanto Contemporary

Each of these pioneering places will no doubt be asking similar questions to Hakanto: how to convince people who have very little, and must struggle each day, that the art on show is for them? How to ensure art is seen as more than the preserve of the elite? How to create a place of comfort for all, from those living high on the hills to the displaced sleeping in the football stadium below?

To achieve these goals at Hakanto, Andrianomearisoa must “first convince the Malagasy artists”, he says. “We need to convince them that being an artist is important to everyone in this country. They can live as an artist and think as an artist, and that benefits everyone.”

“We are under the water, but we can dream,” he says. “Art can do that.”

• Read our interview with Joël Andrianomearisoa here.