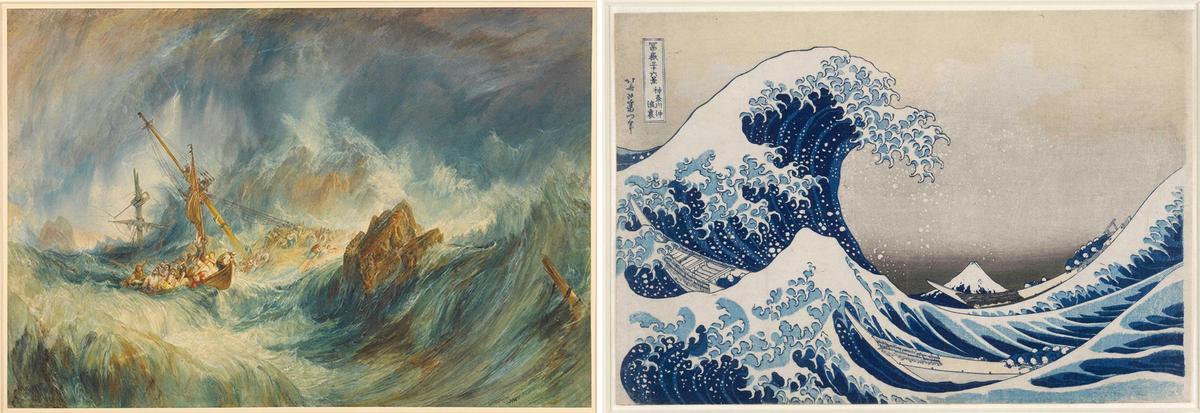

According to an early biographer, J.M.W. Turner viewed publishers who sold his prints as greedy middle men, “huxters of art”. We can easily imagine what he’d make of museums selling his work as NFTs, as the British Museum will this month through the website La Collection. Twenty watercolours will be sold, with prices for the “rarest” starting at €4,999 ($5,660). The iniative follows on from the sale of 200 Hokusai works from the museum's collection as NFTs last year.

That sum gets you a jpeg with no rights, physical or intellectual, on the original image. What you’re really buying is the sequence of code entered onto the blockchain, which is unique and thus tradable. If enough people believe the line of code is worth something then you can sell your Turner jpeg for a profit. Think of it as the emperor’s new code.

La Collection say the NFTs will exist “in perpetuity”, but that’s a bold claim for a technology that has only existed since 2014. I’ve got phones younger than that which I can’t switch on anymore. Meanwhile, the British Museum says the sales will help it “find new ways of reaching people”, but of course it’s about money. Sure, you can call your Turner NFT “art” if you like, but only in the same way a £5 note is art because it has a portrait of the Queen on it.

Worse, the museum demeans itself by getting involved in the alchemy necessary to persuade us that an infinitely reproducible jpeg can somehow be worth thousands. To distinguish them from anything already available for free on Google Images, nine Turner NFTs will be declared “ultra rare” and seven will be “super rare”. To add authority to the pretence of rarity, the British Museum is “retaining” one of each. So they have skin in the game.

The sales pitch from La Collection assures buyers that the NFTs are “extremely collectible and tradable”. The NFT market has so far mostly risen, but you don’t have to be Warren Buffett to see it combines the riskier aspects of an art, land (yes, you can also buy virtual “land”) and tech bubble. We’ll only know when the crash comes if the British Museum has thought through all the moral and legal implications of promoting its collection as an investment asset.

And might the museum even come to regret suggesting reproductions can be cultural objects themselves? When I recently visited the wonderful new Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland, I was fooled by a facsimile of a 16th-century tomb made by the Factum Foundation. I couldn’t believe, even after reading the label, that it was made of plastic, not marble. As someone whose art historical raison d’être is being able to distinguish real from fake, I found this disturbing.

I used to believe that the essential value of an original object was its uniqueness as a visual record of the artist’s creation; a copy could never be as “good” as the original. But if we can now so convincingly replicate an original then we must presumably change how we value it, whether for its material authenticity, or its historical or religious significance.

This matters for museums in the business of putting items on public display. If it is now possible to make perfect recreations of, say, the Parthenon Marbles, or the Benin Bronzes, then the case for retaining the original on a wall in London for public display becomes weaker, compared with the argument for seeing them in their original context. The British Museum, in giving cultural validity to meaningless reproductions, blurs the lines between real and fake at its peril.