A gallery converted from a former school and bank in the heart of Bishop Auckland in County Durham, England, is billed as the UK’s first museum dedicated to the art, history and culture of Spain. Its opening on 15 October is also the latest milestone in the bold Auckland Project, using culture to revive the fortunes of a small northern town left in tatters by the death of the coal mining industry.

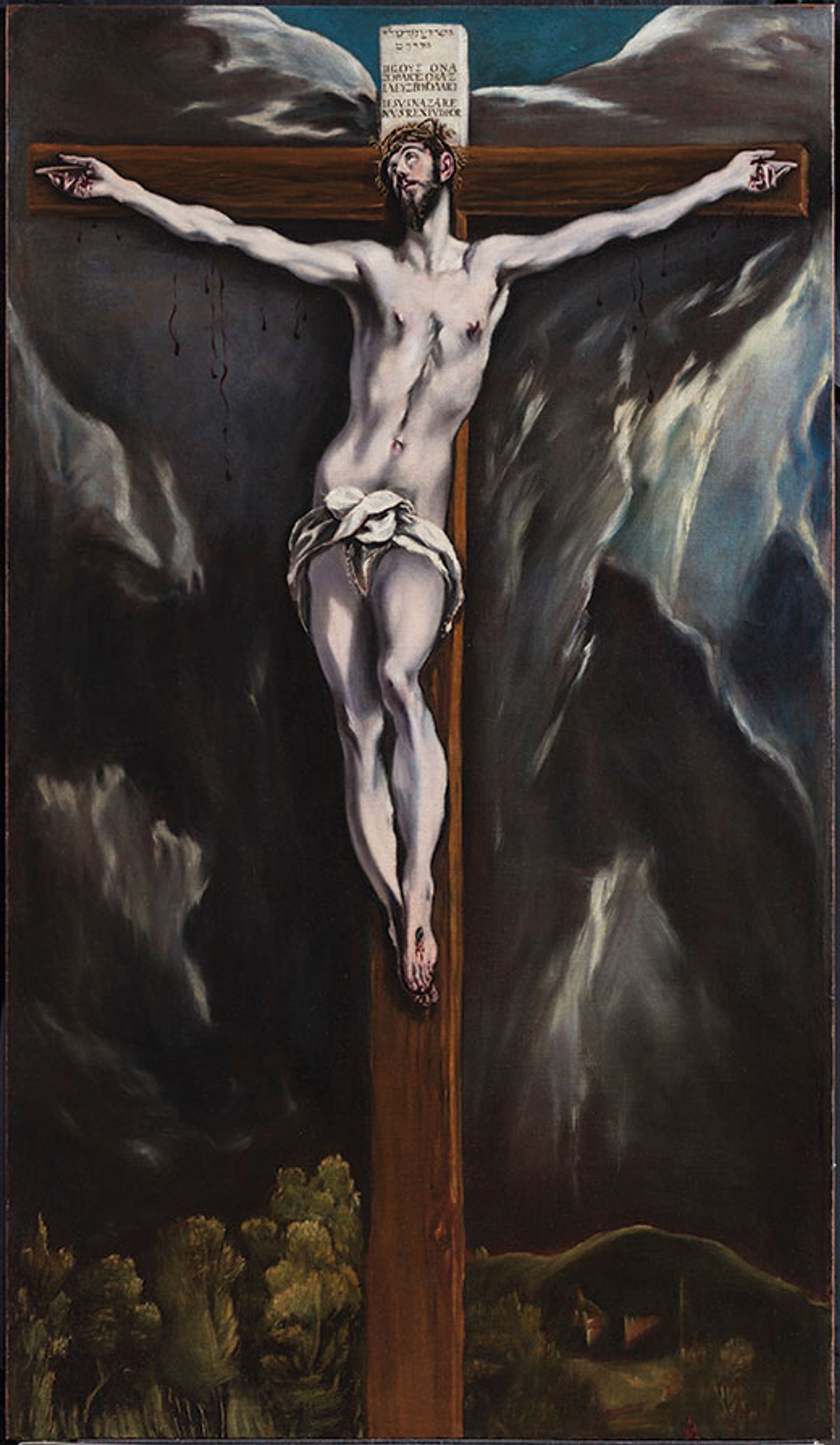

The Spanish Gallery’s inaugural exhibition, designed by the Edinburgh-based Studio MB and created with Durham University’s Zurbarán Centre for Spanish and Latin American Art and Culture, will include works by Spanish Golden Age painters and a room devoted to an imposing El Greco crucifixion acquired with support from Art Fund. Other galleries explore the enduring Spanish theme of death and the fruitful fusion of Spanish and Islamic art, with facsimile objects and interiors created after 3D scans by the Madrid-based Factum Foundation.

Many pieces are from the personal collection of Jonathan Ruffer, the financier who is the main backer of the £150m Auckland Project. Additional loans are planned from Museo del Prado, the Hispanic Society of America and other major collections of Spanish art.

Elsewhere in Bishop Auckland, Ruffer’s redevelopment includes the palace of the Prince Bishops, for centuries the town’s warrior priests and secular rulers; their deer park and walled garden; a new tower on the market square with sweeping views; and an outdoor community play staged by 1,000 volunteers. All this had drawn a million visitors a year before the pandemic hit, and the target is at least five million.

El Greco’s Christ on the Cross (1600-10) is the centrepiece of a room in the new Spanish Gallery Courtesy of the Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland

The Mining Art Gallery, featuring self-taught and amateur painters, opened in 2017 in an old bank building and is an obvious attraction in a county shaped by coal. The Spanish Gallery, located across the market square in handsome, formerly vacant buildings, is unquestionably a harder sell.

Ruffer is leading the curatorial team, the first time he has played such a role, and says he is not an academic but a storyteller. He argues that the gallery cannot fail on its own terms: “Most people in the sector have to spend far too much time worrying about who will come. Being rich allows you to look at things in another way. We have a collection here that is very authentic, full of truths, very powerful—and we have the advantage of not giving a stuff about who comes.”

However, it is clear this is not the whole story. Ruffer has long been gripped by the power and spiritual intensity of Spanish art. When the Church Commissioners, who manage the Church of England’s assets, proposed in 2012 to sell 12 monumental Zurbaráns that had hung on the walls of the bishops’ palace since 1756, Ruffer paid £15m to keep them together. He then bought the largely derelict palace to preserve their home, and since then the project has grown remorselessly. The new gallery will display the only painting separated from the palace set since the 18th century, on loan from the Grimsthorpe and Drummond Castle Trust.

“It’s all about regeneration,” Ruffer insists. “It all has to serve what I am interested in, the town picking up again as a thriving place.”

Still, if nobody comes to the Spanish Gallery, it is hard to believe he will take it on the chin. This time it is personal.