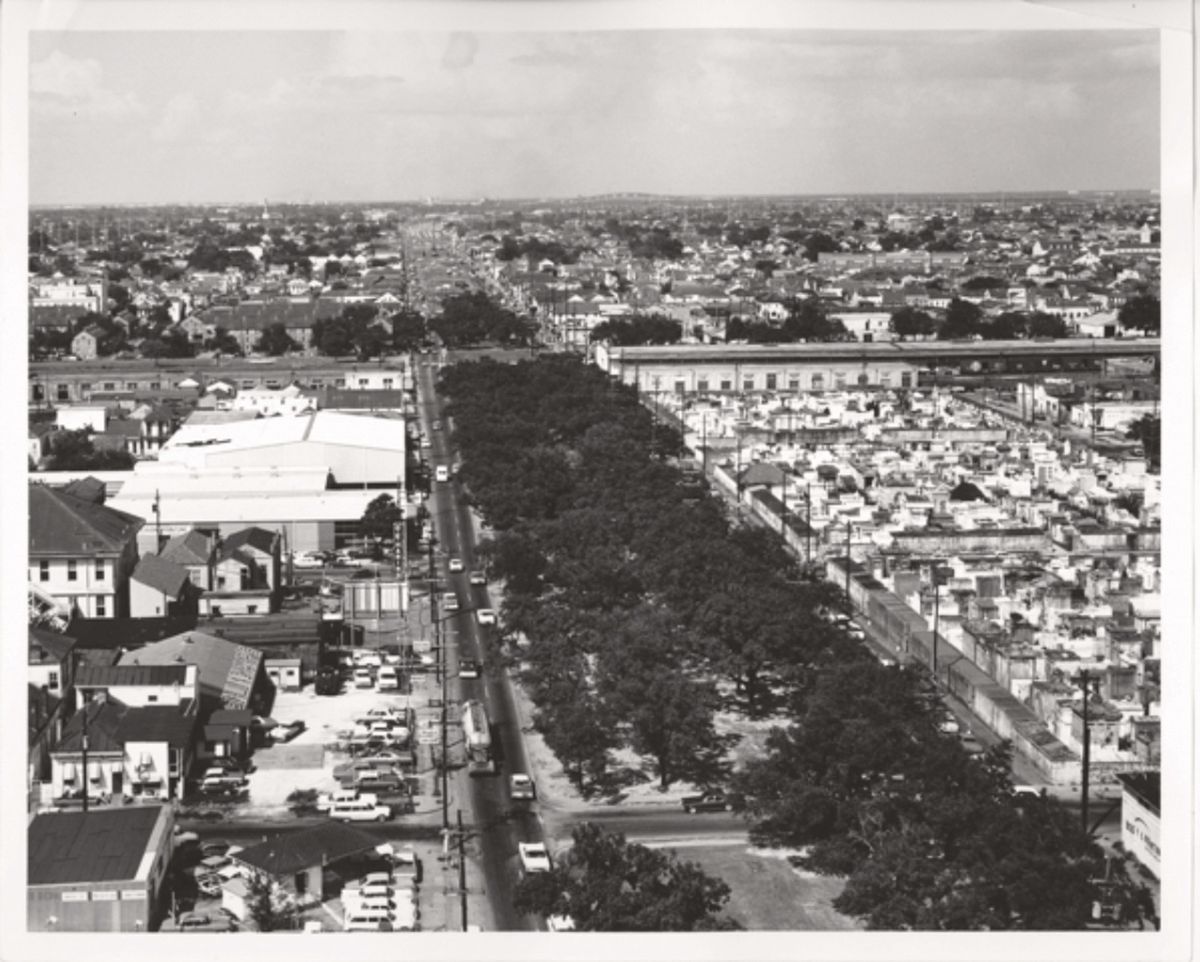

The oak trees were hundreds of years old. “They lined North Claiborne Avenue as far as you could see,” New Orleans artist Katrina Andry says.

The avenue, a wide boulevard dotted with azalea bushes, and with sunlight seeping through the oaks’ canopies, was at the centre of Tremé, a historic Black neighbourhood in New Orleans celebrated today as the birthplace of jazz and a focal point of the city’s Mardi Gras festivities. Tremé was, says Andry, “one of the oldest Black neighbourhoods in New Orleans and America at large; a community that dates back to slavery”.

“The avenue was a gathering place,” adds Andry, a participating artist in the recent fifth edition of the Prospect New Orleans triennial. “Each of the 50 businesses on Claiborne was owned by a local family. Carnivals would start and end there. It was really important for Black folks, especially during the time of segregation; it was the centre of life.”

Katie Pfohl, a curator of contemporary art at the New Orleans Museum of Art, refers to Tremé as “a birthplace of so many of the things we love about New Orleans culture”.

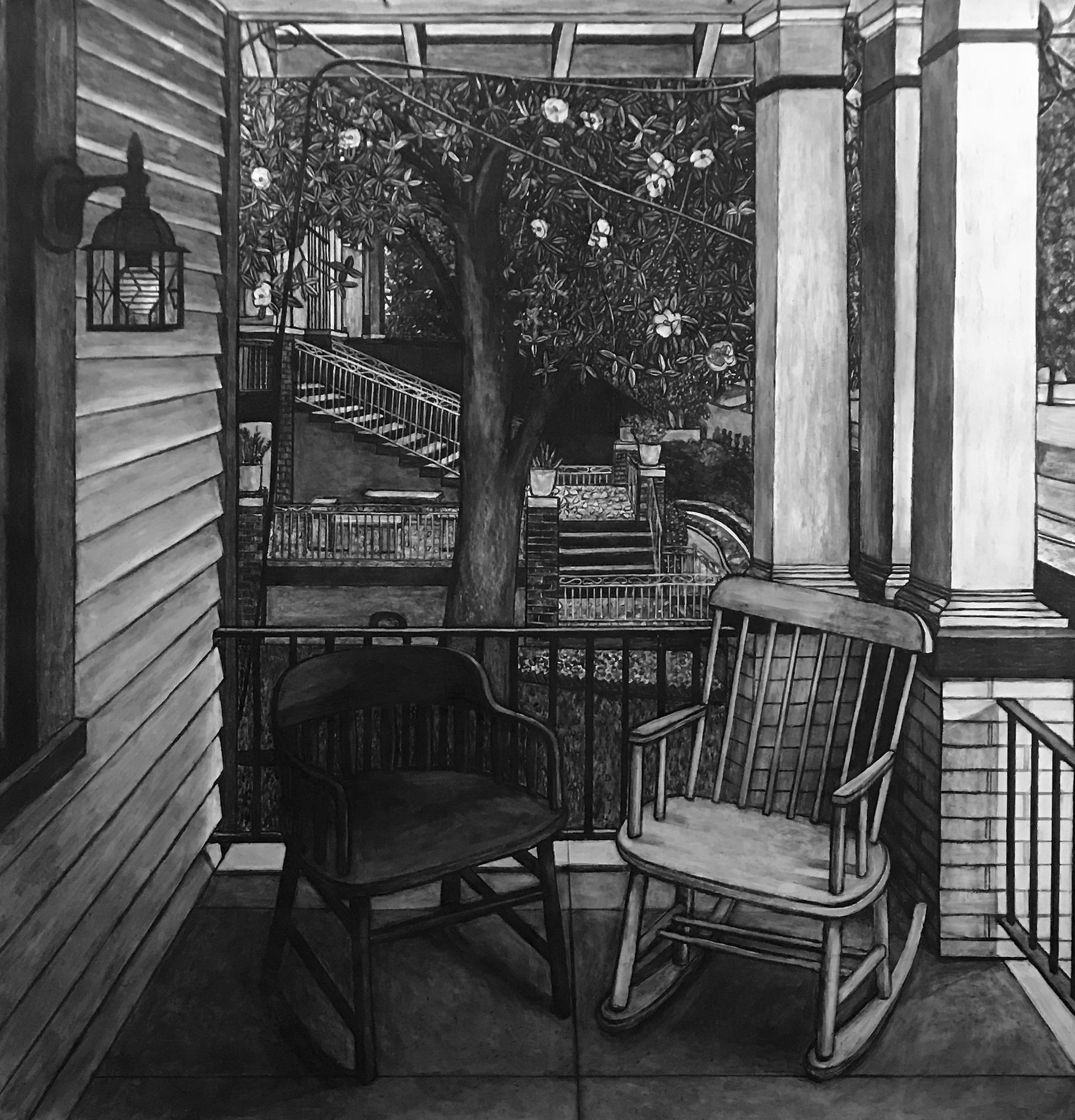

Willie Birch, Waiting for a Serious Conversation About the History of New Orleans (2017) Image courtesy of the artist and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans

But in 1956 President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act, a huge infrastructure initiative triggering construction of a network of highways stretching across America. In New Orleans, planners wanted to connect the downtown business district to Interstate 10, the huge highway that crosses the American South. Tremé, it was decided with little consultation, was where the connector would be built.

The city government of the day signed off on Claiborne Highway as quickly and secretively as it could. “They scheduled public meetings about the highway only hours before, and without announcing them,” says Pfohl. “There was an active effort to suppress protest.”

A community reshaped

Many residents of Tremé did not know what was about to happen when the bulldozers trundled onto Claiborne Avenue in February 1966. They fought to stop the construction, but it was too late. The oak trees were ripped out and, by the estimates of one advocacy organisation, 500 homes were ultimately torn down. “People were displaced,” says Andry. “Businesses at the centre of community life had to close down. People had to learn to live with a flyover right over their heads.”

“It devastated the community,” says Pfohl. “In the time since, it has remained a place of gathering, but, rather than being a green space, it’s a concrete forest.” Street artists, Andry notes, have painted oak trees on some of the concrete pillars supporting the flyover.

For so many artists and culture-bearers, the overpass exists as one of the most challenging and difficult chapters in what is a very fraught history in New Orleans when it comes to gentrificationKatie Pfohl, curator

The Claiborne Expressway, a huge elevated overpass, effectively split Tremé in two. It has stood there ever since, the thundering of thousands of speeding cars overhead the constant backdrop of community life. It has become a source of inspiration and concern, explicitly and implicitly, for generations of artists working in New Orleans.

Paul Stephen Benjamin, Sanctuary (2021), installation view of Prospect.5: Yesterday we said tomorrow (2021-22) at the New Orleans African American Museum, New Orleans Courtesy Prospect New Orleans. Photo: Jose Cotto

The New Orleans African American Museum is built on a former plantation now situated just two blocks from the Claiborne Expressway. It has been an important venue for the Prospect triennial, and during the most recent edition, exhibited works meditating on the impact architecture and infrastructure has had on the Black experience in New Orleans. Most notable was Sanctuary (2021), a sculptural work by the Chicago-born artist Paul Stephen Benjamin inspired by the vernacular and improvised architecture that surrounds the flyover.

The third edition of the triennial, in 2015, included a site-specific installation by the New York artist Gary Simmons, Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark (2014), inside the Tremé Market Branch—then a derelict building, but formerly a community bank dating back to the 1930s, which sits directly alongside the highway. The bank is now a music and wedding venue, an indicator of the urban renewal underway in Tremé.

Concrete forest coming down?

Last November President Joe Biden signed his Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law, which includes $550bn until 2026 for improvements to roads, bridges, mass transit and other infrastructure. Biden pledged to prioritise projects that are racially equitable and seek to balance longstanding disparities in how the government locates and builds infrastructure projects. Officials cited the Claiborne Expressway as an example of what the law actively would not do. Instead, construction and development initiatives will be proposed and determined by local governments. Extensive consultation is built into the process.

The Claiborne Highway in Tremé Photo by NewUrbanism, via Flickr

Although the figure remains variable, around $1bn has been earmarked to renew the Claiborne Expressway. That means members of the Tremé community must decide what to do with the concrete giant that continues to hunker over Claiborne Avenue.

“I see no reason for it, and think it could be taken down,” Andry says.

But not everyone agrees. Another proposal is to remove the arteries that allow traffic to flow from the interstate highway, pedestrianising the flyover and making it something akin to the elevated High Line park in Manhattan.

Pfohl was the curator of Changing Course, a group exhibition that opened during the 2018 New Orleans Tricentennial and examined the overpass’s impact on the Tremé community. The show, Pfohl says, “asks how we can pay homage to something that was never allowed to exist”.

“The future of the overpass has become a central conversation in New Orleans around that very questioned phrase of ‘urban renewal’,” Pfohl says. “For so many artists and culture-bearers, the overpass exists as one of the most challenging and difficult chapters in what is a very fraught history in New Orleans when it comes to gentrification. And ill thought[-out] gentrification continues to impact badly on the cultural legacies of the city.”

Katrina Andry, Diverge Divest Deny (repeat) (2018), mixed media installation

Courtesy of the artist

Changing Course included a body of work by Andry titled Diverge Divest Deny (repeat), which repurposed archival imagery of Tremé before the bulldozing of Claiborne Avenue as a way to imagine the community that might have flourished if the highway had not been built.

Andry grew up in New Orleans East, an area of the city that was hit particularly hard by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. “After the hurricane, the area I grew up in was neglected,” she says. “It wasn’t redeveloped after it flooded. Now it’s in a state of blight.”

The lessons of Claiborne reverberate in the issues facing the city today. “New Orleans is often spoken of in terms of decay,” she says. “But Claiborne was a place of beauty. I wanted to imagine what it could have been, and what it could still be.”