Fra Bartolommeo, Head of a Young Woman, Looking Down to the Left (1490s)

Old Master Drawings evening sale, Sotheby’s, New York, 26 January

Estimate: $400,000-$600,000

This sensitive study of a young woman, in black chalk heightened with white and presumably done from life, was intended as the basis for a Madonna. It is thought to be a particularly early work by Fra Bartolommeo, done before he became a monk, as recently confirmed by the scholar Chris Fischer. The 26cm by 20cm drawing was last seen in public in 1927, when it was bought by the grandfather of the present owner at a sale in Amsterdam for the substantial sum of 892.50 guilders. Greg Rubinstein, Sotheby’s head of Old Master drawings, says that, although he expects it to sell for more than $400,000, fine early Renaissance drawings like this come to the market so rarely that it is very hard to put a precise value on them. He describes it as “a classic Renaissance image, with all the contemplative beauty and softness of handling in the chalk that one might see in a Leonardo, yet with a touch of the firmness and power, and mastery of outline, that characterises the artists of the previous generation, such as Botticelli and Fra Bartolommeo.”

Moulded copper flying Angel Gabriel weathervane, attributed to J.W. Fiske (around 1890) Courtesy of Christie’s

Moulded copper flying Angel Gabriel weathervane, attributed to J.W. Fiske (around 1890)

The Collection of Peter and Barbara Goodman, Christie’s, New York, 20 January

Estimate: $60,000-$90,000

This weathervane, depicting the Angel Gabriel wearing a billowing dress and blowing a horn to herald the Lord’s earthly return, is thought to have been modelled on an 1893 design published by the American decorative iron manufacturer J.W. Fiske. It was first owned by Adele Earnest, a founding trustee of the American Folk Art Museum in New York. She sold the vane to the pioneering folk art collector Stewart Gregory, who lent the work for a display of more than 40 vanes and sculptures at the US pavilion at the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka. The sale of Gregory’s collection upon his death in 1976 achieved $1.3m and was considered a watershed moment for the folk art market. There, this weathervane sold for $16,000 and found a starry new owner: the American film director Mike Nichols (1931-2014), who won the Academy Award for Best Director for The Graduate (1967).

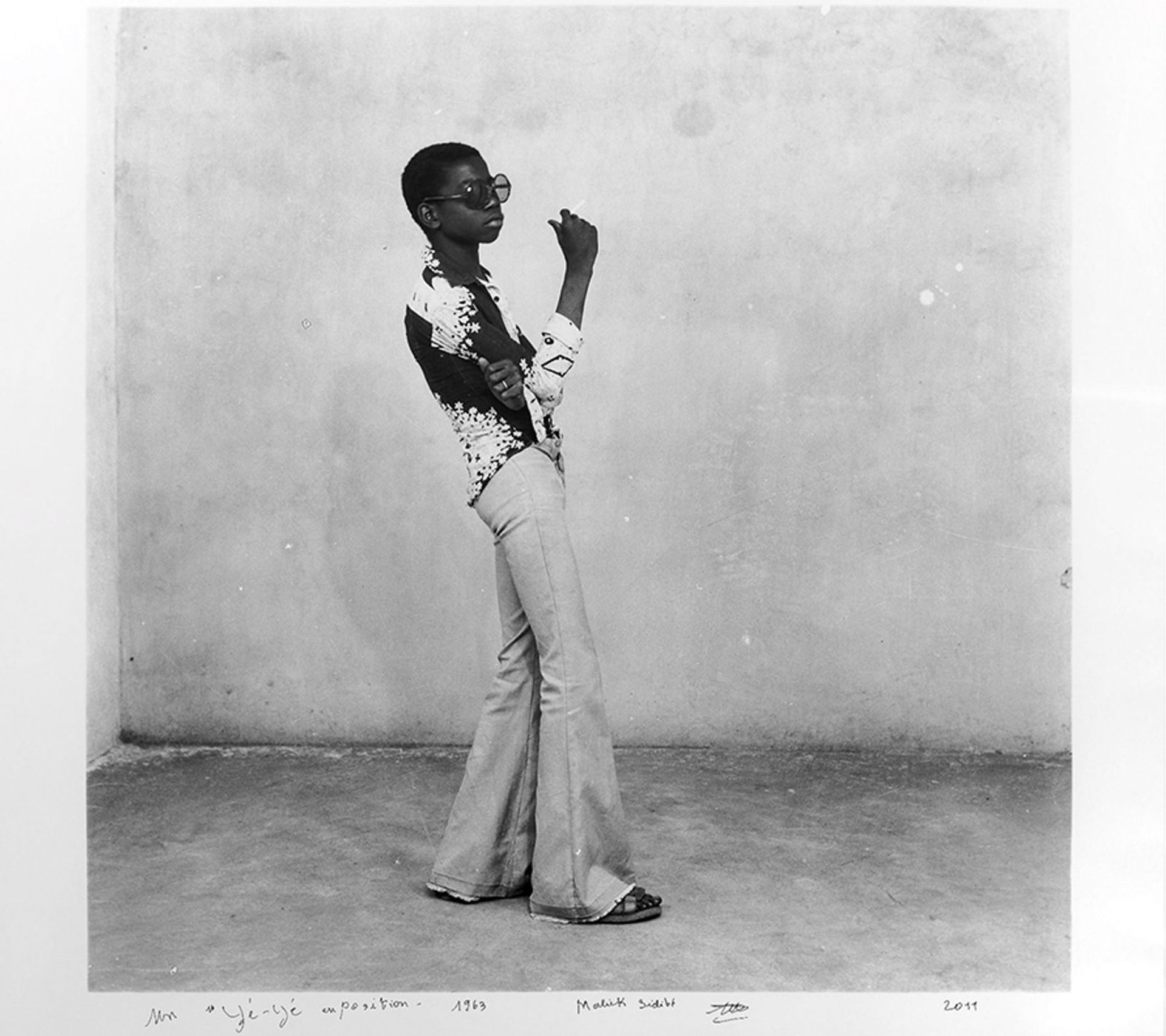

Malick Sidibé’s Un yé-yé en position (1963, printed in 2011) Courtesy of Artcurial

Malick Sidibé’s Un yé-yé en position (1963, printed in 2011)

African Contemporary and Modern Art, Artcurial, Galerie Venise Cadre, Casablanca, 30 December

Estimate: €12,000-€15,000 ($13,500-$16,900)

In 2007 Malick Sibidé won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement Award at the Venice Biennale, the first African and the first photographer to do so. Hailing from Mali, Sibidé is best known for capturing the vibrant nightclub scene and stylish youth of a newly independent Bamako, the Malian capital, in black-and-white. This photograph was taken in 1963, a year after he established his own studio. It depicts a young man in bell bottoms holding a cigarette and striking a concertedly casual pose—a trademark of the artist. Sidibé, whose eye for composition was trained by an early career in drawing, always insisted that his subjects never look “stiff”. Sidibé’s work is noted for its ties to music culture and this work is no exception: its title refers to yé-yé, a style of pop music in the 1960s popularised by musicians such as Serge Gainsbourg, and whose practitioners embodied the freewheeling attitude of the era. It was bought by the consignor, a Belgian collector, from Galerie Magnin-A in Paris. Sidibé’s auction record stands at £35,000, achieved at Sotheby’s London in April 2021.

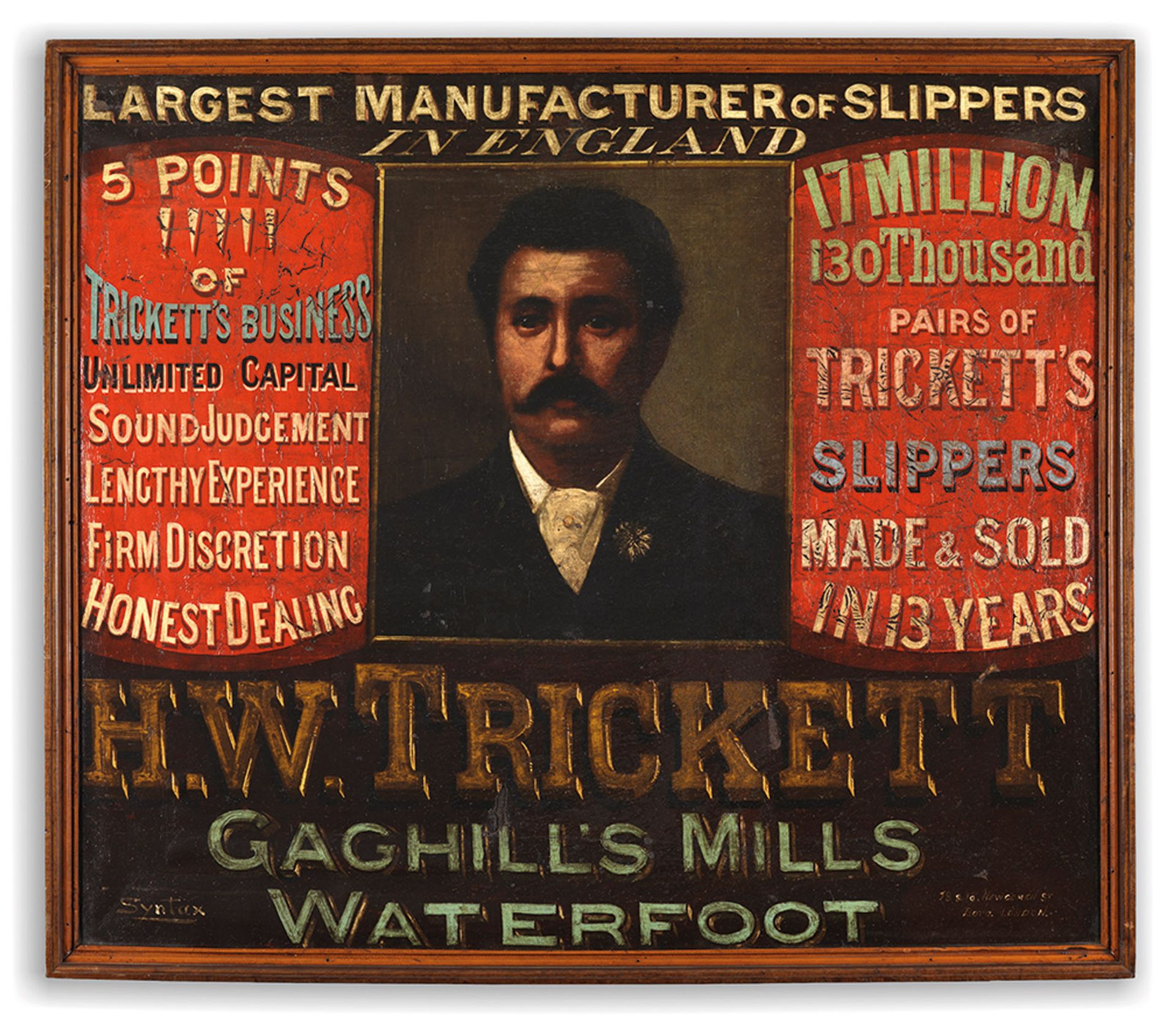

Shoemaker’s trade sign for “H.W. Trickett”, English (around 1900) Courtesy of Robert Young Antiques/Artmedia Press

Shoemaker’s trade sign for “H.W. Trickett”, English (around 1900)

With Robert Young Antiques at The Winter Show, Park Avenue Armory,

New York, 21-30 January

Price: $15,000

This trade sign, unusually painted on heavy canvas, was sourced by the London-based folk art specialist Robert Young directly from the Lancashire shoe factory for which it was made. It is the only trade sign that Young has found that includes a portrait of the “(presumably narcissistic) founder of the company”, in this case, Henry Whittaker Trickett, known far and wide for his excellent slippers. But what makes a good sign? Being able to trace its origin, Young says—but “they also need to reflect their period and trade, to have strong graphics and retain original historic surface, inclusive of wear, weathering or incidental losses”. Scale is important, too (this one is large, at 40 inches high) although signs of this size were usually painted on wooden panels, which inevitably tend to shrink, split or weather (creating what are known as “ghost signs”). This one, though, is in remarkably good, untouched condition, “explained by the fact that it was made to be hung inside the factory, rather than outdoors, where it would be exposed to the elements”, Young says.