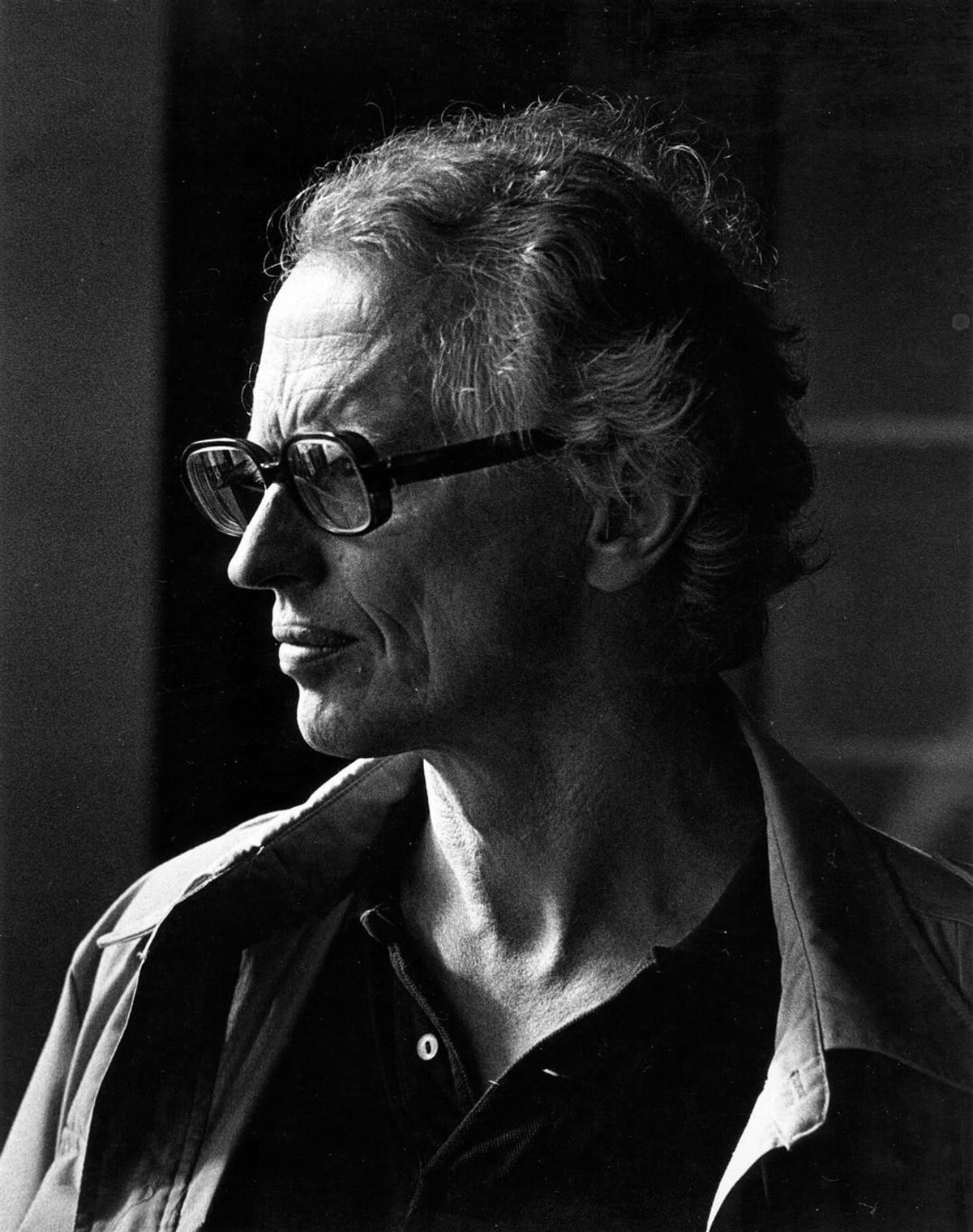

Frederick C. Baldwin, the much-loved and storied photographer and collector known for co-founding Houston’s FotoFest, America’s leading photography festival, died suddenly on 15 December at age 92.

In 1955, when the 26-year-old Baldwin was barely a photographer, he managed to talk his way into Pablo Picasso’s south of France home whilst holidaying in the area. The portraits the young chancer took of the famous artist launched Baldwin’s photographic career, one that encompassed the Arctic, Afghanistan, India and, most significantly, the Civil Rights Movement in the American South.

But Baldwin, who went by Fred, will be remembered primarily for the photography festival he founded with his surviving wife Wendy Watriss in Houston, Texas, in 1986, and which today is considered one of the most important photographic exchanges in the world.

Mark Sealy, the influential British curator and director of London’s Autograph ABP agency, was commissioned by Baldwin to curate African Cosmologies: Photography, Time and the Other, a show featuring more than 30 African artists, at the 18th edition of FotoFest in March 2020.

Sealy remembers Baldwin as a “shining example of generosity”.

“When you met Fred and Wendy, you were struck by how genuinely open they were,” Sealy tells The Art Newspaper. “And they were open at a time when a lot of cultural organisations around the world simply were not. They really believed in providing a space for different types of photography. That’s what drove them.”

FotoFest, Sealy notes, would often provide funding and exhibition opportunities for Black British photographers who were not offered comparable opportunities at home in the UK.

“They gave Black British photographers a really important platform very early in the game,” Sealy says. “It was transformative for us.”

Baldwin, then, used FotoFest as a platform for minority-view photographic art decades before it became a mainstream endeavour. “When you met Fred, you thought: ‘Oh God, big guy, gruff American, here we go,’” Sealy says. “But underneath was a real example of the politics of care.”

“He cared about different viewpoints. Even though he might not have fully understood them, he was always open to them, and he was prepared to learn,” Sealy says. “And that’s all we’ve ever asked for. The arts is about the ability to learn from each other’s experiences, and Fred embodied that.”

Baldwin’s generosity towards photographers from beyond America, and who had yet to make their name, is a recurring testament to his character. Shahidul Alam, the renowned Bangladeshi photographer who has collaborated closely with Fotofest, remembers meeting Fred and Wendy the first time he ever visited the US.

“I had never met them before,” Alam says. “There was no reason for them to know me. I made a cold call and turned up at Houston. Not only was I received with wonderful warmth. They fed me, took me round Fotofest and offered me their couch to sleep on. I was used to such hospitality for strangers in Bangladesh. I hadn't expected it in the US. We stayed friends ever since."

The son of an American diplomat, Baldwin was born into privilege in Switzerland in 1929. He lived a peripatetic youth, constantly moving from one country to the next, initially in pursuit of his father’s work and then, after his father’s death when Baldwin was just five, as he tried to seek his place amongst the homes of family, friends and schools he was sent to and variously kicked out of. The rootlessness of his childhood drove him to rebel, and he initially failed at his studies.

Unsure what to do with himself, Baldwin signed up with the US Marine Corps and was deployed to serve in America’s Korean War, where he was awarded two Purple Hearts, and where he took some of his earliest photographs.

In his 2019 memoir, Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom, Baldwin remembers the years after the Picasso shoot, during which, on expeditions with his camera, he photographed Sami reindeer herders in the Lapland region of northern Europe, as well as the great tundras of the Arctic.

“What was magical for me was that a little tiny camera could serve as a passport to the world, as a key to opening every lock and every cupboard of investigation and curiosity,” Baldwin wrote of discovering the power of photography.

Baldwin eventually returned to the US and settled in Savannah, Georgia in the American south, where he married his first wife, Monica. He recalls in his memoir the horrible impact of witnessing a Ku Klux Klan rally in Alabama in 1957, before then becoming immersed in the Civil Rights Movement. He met Hosea Williams, a civil rights leader and ordained minister who was close to Martin Luther King Jr. and began attending and photographing activist meetings of Williams’s Chatham County Crusade for Voters. This formative period led Baldwin to begin to view photography as a tool of social use rather than a reductive way of expressing his own personal experiences. He learnt to take the ego out of his work.

In his memoir, he wrote: “Economic discrimination was not news to me, nor was segregation or class division, but the difference lay in my becoming intimate with these realities in a totally new way. And I was making photographs in a new way—for a cause, a cause that I knew was right.”

He met Watriss, then a young journalist, in 1970 in New York City. Within a year of meeting, they had set out on the time-honoured road trip across America; he would photograph the continent beyond, she would write of what and who they discovered. The pair soon married and founded FotoFest in Houston in 1986, three years after they attended the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in the south of France.

In an interview with the Houston Chronicle, Baldwin said the festival was founded as “an act of anger”—a reaction to the way the medium of photography, and especially photography of events and experiences beyond the mainstream of American life, was so routinely ignored by the established order of the art world. FotoFest’s founding mission, from its creation to this day, was “to bring together a global vision of art and cross-cultural exchange with a commitment to social issues”. The festival hit a chord and grew quickly in both stature and renown. Today, it is firmly established as one of the leading photographic exchanges in the world.

Baldwin’s interest in the minutia of hosting the festival never waned, according to British photobook publisher Dewi Lewis. “At every FotoFest I’ve ever attended over the last 25 or so years—Fred has always been there, always a pleasure to meet and talk to, always someone who brightened up the room,” Lewis says. “He had a warmth and a wit that could charm anyone, but it often hid the extent of his own achievements, and his more serious side as a photographer, author, educator and social activist.”

Baldwin is survived by Watriss; Frederick Breckinridge Baldwin, Charles Grattan Baldwin, Judith Moncrieff Baldwin and Annika Adams Baldwin.