After a years-long research process, the Kunstmuseum Bern will give up 29 works of art bequeathed by Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of a notorious Nazi-associated art dealer, including two Otto Dix watercolours that will be restituted. However, the Swiss museum will retain close to 1,100 works whose ownership history during the Nazi period of 1933-45 remains murky.

The Kunstmuseum Bern was unexpectedly named in 2014 as the sole beneficiary of Gurlitt’s last will, made two years after his tainted art hoard was confiscated by German authorities from his homes in Munich and Salzburg. The museum has now largely concluded its investigation into the Gurlitt bequest, comprising around 1,600 works by artists including Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet and Max Beckmann.

Following two Gurlitt provenance research projects undertaken in Germany, the museum embarked on its own study in 2017, when it took possession of the first pieces in the collection. Concerns had been raised about the trove’s connections to Nazi art plunder when the bequest was announced, says Nina Zimmer, the museum’s director since 2016. “There was a lot of pressure not to accept [the works],” she says, as well as a legal challenge to the inheritance from a Gurlitt family member. “The board decided to accept in order to bring the discussion [around Nazi loot] to a Swiss museum and to take responsibility.”

A restorer examines works on paper under the microscope © Kunstmuseum Bern

The museum became the first in Switzerland to set up a dedicated provenance research department. “We fundraised for it,” Zimmer says. “It’s still to this day completely financed by [private] foundations.” Led by the scholar Nikola Doll, the current team of four is supplemented by up to eight external experts. Because of a lack of specialist provenance researchers in Switzerland, the museum has also partnered with two local universities to run “programmes to educate a new generation”, Zimmer says.

Researchers used a traffic-light system to sift through the Gurlitt bequest. Twenty-eight works are labelled “green”, meaning they have a consistent clean ownership history in 1933-45. At the other end of the spectrum, nine “red” pieces were definitively found to have been Nazi-looted from Jewish owners; these have already been restituted to the heirs.

“Unfortunately, the majority of cases remain incomplete, even after extensive research,” Zimmer says. The study found that there was no direct evidence or implication of looted art for 1,089 “yellow-green” works. They will remain in the Kunstmuseum Bern’s collection unless further evidence emerges to the contrary. “That is always possible,” Zimmer says. “We’re always ready to continue the research and shift category.”

However, the museum has announced it will renounce ownership of 29 “yellow-red” works that have incomplete wartime provenance but are suspected of being Nazi-looted art. “In the past the solution was to keep the work and wait for new sources,” Zimmer notes. “We felt it was time to act even in these more difficult cases.”

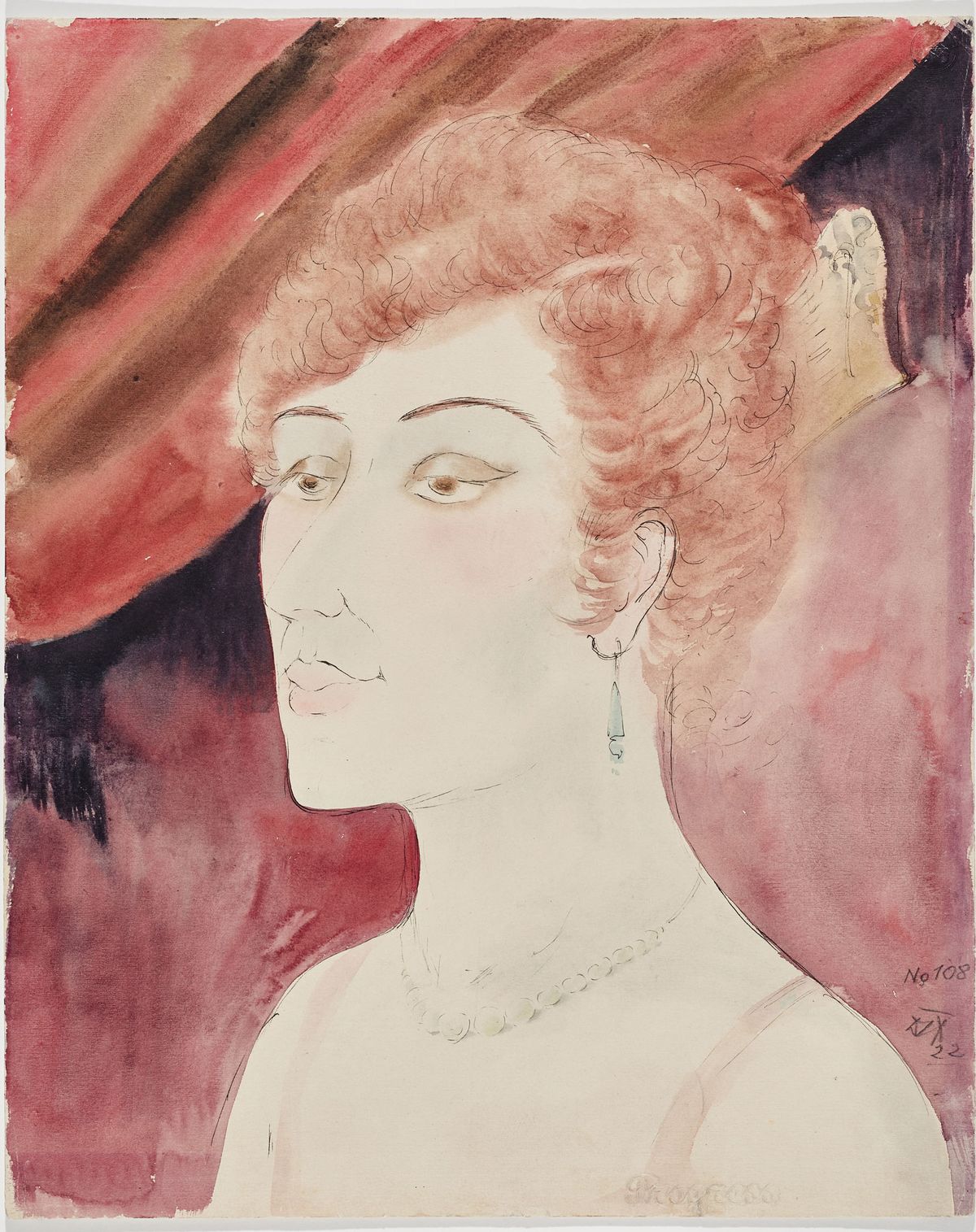

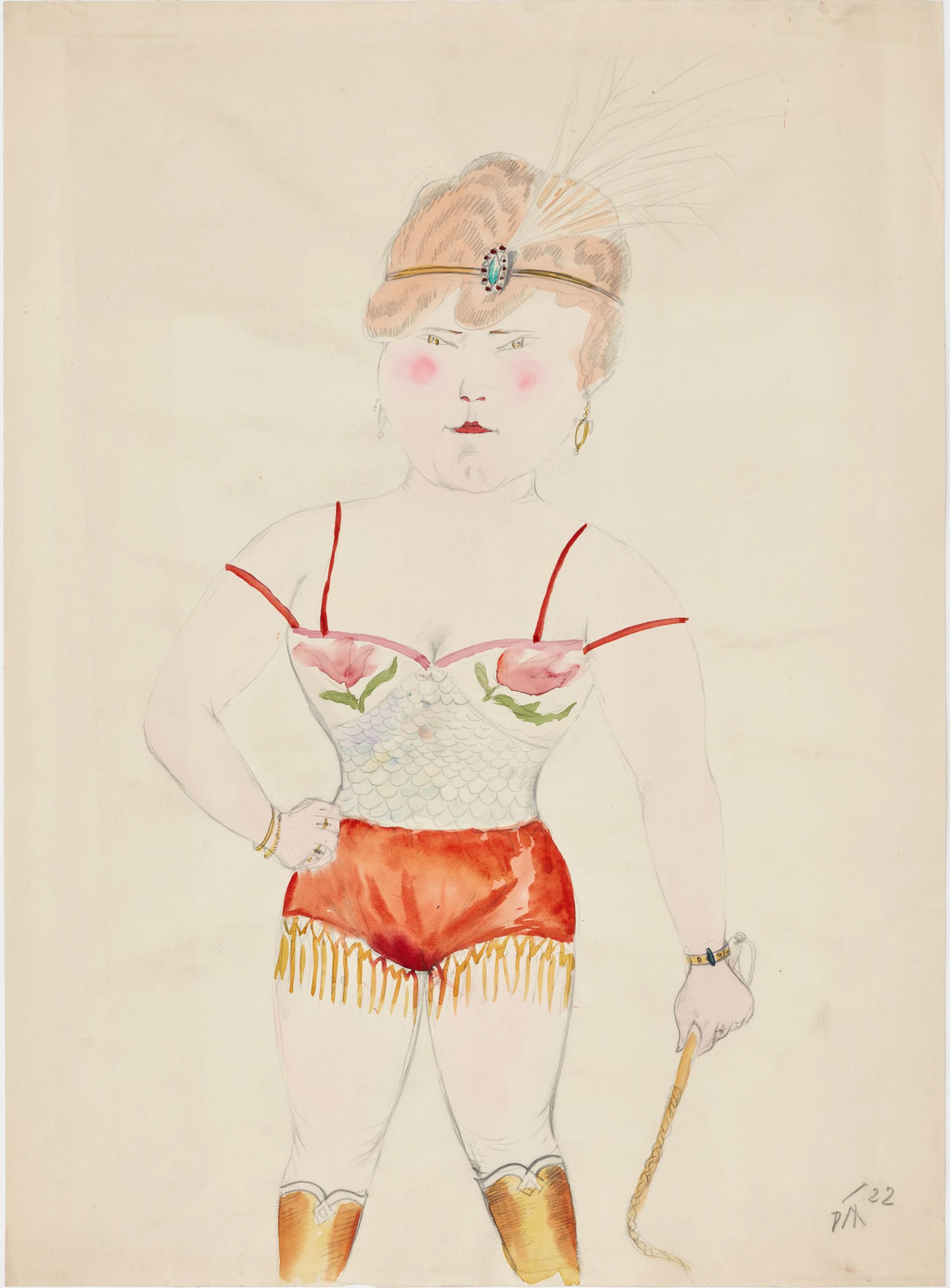

Among them are two 1922 watercolours by Otto Dix, titled Dame in der Loge and Dompteuse, that will be returned to two different families. The Kunstmuseum Bern Foundation decided on 5 November to jointly transfer the works to the descendants of Ismar Littmann and Paul Schaefer, pending an agreement between all the parties. While the Littmann heirs have a longstanding legal claim to the works, the museum traced the Schaefer family during its research.

Otto Dix, Dompteuse (1922)

The museum is considering a restitution claim from the heirs of Fritz Salo Glaser to 13 “yellow-red” works and says it will pursue further research in the hope of tracking down rightful owners for nine pieces by Pierre Auguste Renoir, Tiepolo, Georg Grosz and others.

Five other works in the same category will be transferred to the federal authorities in Germany “under the condition that there is no further need for research, no claims are filed and no potential rightful owners are evident”, according to a museum statement.

The entire Gurlitt bequest and the results of the provenance research are available to view in a database online. Zimmer says: “We hope that in being fully transparent in publishing our knowledge and images, if somebody has information that would facilitate the research [they will come forward].”

The works remaining in the Bern collection will feature in an exhibition scheduled for September 2022 titled Taking Stock: Gurlitt in Review. The controversial trove will be displayed comprehensively for the first time, accompanied by archival materials and testimonies from Cornelius Gurlitt and his father, Hildebrand Gurlitt. “With this exhibition, the Kunstmuseum Bern also addresses the challenges a museum faces when dealing with a bequest from an art dealer from the time of National Socialism as well as the ethical questions this raises,” it says in a statement.

Meanwhile, the museum will shift its provenance research efforts towards its existing collection. Three works—Matisse’s Les anémones (1923), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Dünen und Meer, Fehmarn (1913) and a 1930 landscape by Max Slevogt—have already raised “red flags”, Zimmer says. “Now we need to deepen the research.”

Seven years on from the Gurlitt bequest, there are signs that Switzerland is becoming more receptive to discussions of Nazi-looted art. The city of Zurich is responding to calls for further provenance research into the controversial collection of Emil Georg Bührle, who sold arms to Nazi Germany and bought art confiscated from Jewish owners, after masterpieces from the Bührle Foundation went on show at the Kunsthaus Zurich. And a Swiss lawmaker has secured cross-party support for a motion in parliament to set up an independent panel that would assess restitution claims for art in Swiss museums.

Welcoming the new motion, Zimmer says: “There’s a before and after Gurlitt in the debate. Because this was a hugely popular case and widely publicly discussed... That gave an importance to the debate. I think the public opinion has shifted.”