The celebrated American photographer Sally Mann was tonight announced as the winner of the 9th Prix Pictet for her ghost-filled images of Virginia’s Great Dismal Swamp ravaged by wildfires.

The series, titled Blackwater, was shot near so-called Point Comfort, "the grotesquely ill-named spit of land where the first slave ship docked in America," Mann writes of the series, referring to the boat that arrived from Africa in 1619 holding 20 prisoners. The captives were sold at auction, ushering in the long era of slavery in what would become the United States of America.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the densely forested swamp was used by slaves as a forbidding place to hide in when they attempted to escape the bondage of their owners. The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow described the swamp as "a place where hardly a human foot could pass, or a human heart would dare”.

At times during early American history, communities of refugee and fugitive slaves were able to live in hiding, and without detection, in the midst of the swamp. The Underground Railroad, the network of secret routes and safe houses established to help slaves reach free states, is said to have existed in the swamp.

Mann writes that the people living under bondage "viewed the swamp as preferable to the living hell of enslavement."

"Slithering with snakes, often venomous, the air thick with biting insects and the heavy foliage offering protection to panthers, bear and alligators, the swamp contained an enemy even greater to the maroons, as escaped slaves were called: the slave catchers and their fearsome dogs," Mann writes. "Angry slave catchers and owners, operating on the ‘dead or alive’ theory, sometimes surrounded the maroon swamp communities and set fire to them, burning their quarry alive. For the inhabitants, even that was preferable to being returned to their owners and the excruciating punishments that would ensue."

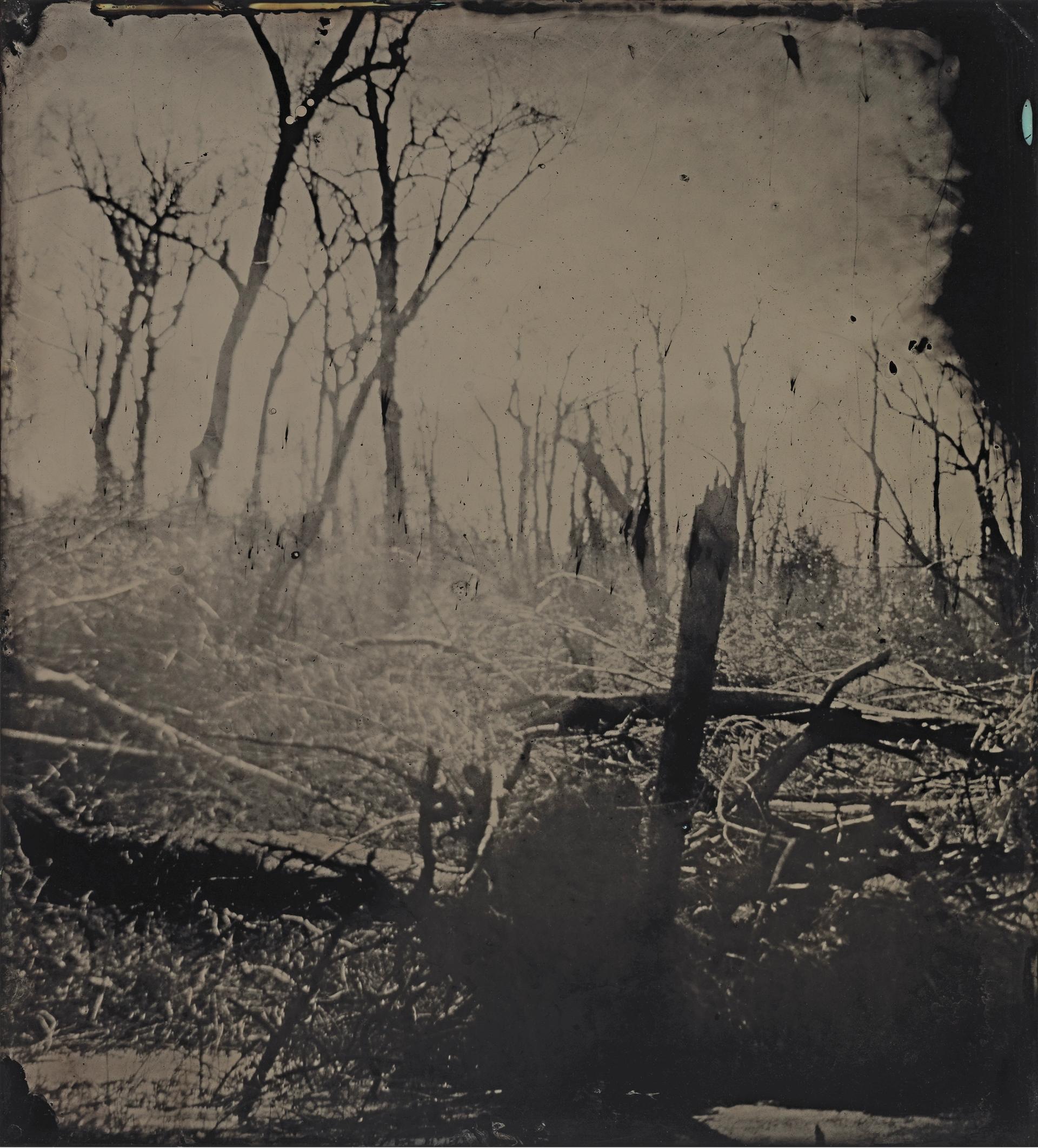

Blackwater 15, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Mann photographed the swamp between 2008 and 2012. After lightening struck during a drought, a series of rolling wildfires gutted the swamp’s teeming ecosystem. She captured the charred landscapes using a large-format camera, a signature of her career, before conjuring the images in monochrome tintypes using wet collodion-coated glass plates — a photographic process that dates back to the age of slavery.

"Thick smoke billowed up ceaselessly, not just for days or weeks, but off and on for years," Mann writes of the wildfires. "In some kind of poetic, metaphoric righteousness, even the soil itself burned."

Yet Mann wrote it felt appropriate that “a place so filled with pain should, a century and a half later, be devoured by an all-cleansing fire.

“The fires in the Great Dismal Swamp seemed to epitomise the great fire of racial strife in America,” she writes. “The Civil War, emancipation, the Civil Rights Movement, in which my family was involved, the racial unrest of the late 1960s and most recently the summer of 2020.”

The images were first exhibited as part of A Thousand Crossings, an exhibition of more than 100 landscapes that premiered at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC in 2018.

Blackwater 13, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Mann, 70, was born in Lexington, Virginia, in 1951, and raised by a doctor and photography-enthusiast father, a librarian mother, and Virginia "Gee-Gee" Carter, the grand-daughter of a slave employed as a caregiver, and a defining presence in Mann's life.

She began to photograph when she 16, telling the New York Times that her motive at the time was to be alone in the darkroom with her boyfriend, Larry, the man that soon become her husband and father to her children.

Throughout the 1960s, Mann attended the Ansel Adams Gallery’s Yosemite Workshops in Yosemite National Park, California and the Putney School and Bennington College, both in Vermont. She received a BA from Hollins College, Roanoke, Virginia, as well as an MA in creative writing. She gained her first solo museum exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, in 1977.

In 1979, she gave birth to her first child, Emmett. By 1984, two more daughters — Jessie and Virginia — had followed. Her children became ongoing subjects of her photography; images she remains best known for.

Blackwater 20, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Throughout the 1980s, Mann published two photobooks, Second Sight and At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women. Also printed via a wet-plate collodion process, and published by Aperture, At Twelve consisted of a series of portraits of adolescent girls.

In the book’s preface, the American novelist Ann Beattie wrote of how Mann’s portraits explore the search for identity and independence as girls enter into puberty. "When a girl is 12 years old, she often wants — or says she wants — less involvement with adults,” Beattie wrote. Mann’s images, she wrote, show the "vulnerable in their youthfulness”.

One particular image created something of a controversy; a precursor for the storm that followed later in her career.

Mann was photographing a young girl and her mother’s boyfriend. In the book, Mann recalled being struck by the “peculiar familiarity” that existed between the two.

Blackwater 1, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

The image shows the girl looping her arm around the boyfriend’s shoulder, whilst his arms remain slack at his sides. But, in the moment of taking the picture, Mann noticed how the girl refused to stand too close to him. Mann, unable to contain them both in her frame, tried to encourage the girl to move closer. Yet the girl resisted.

Months later, the girl's mother shot and killed the boyfriend, later testifying in court how, as she worked night shifts at a local shop for truckers, he would stay at home and harass and abuse her daughter. In the book, Mann wrote: "The child put it to me somewhat more directly".

The image is a microcosm for the career Mann would go on to have, for few contemporary image-makers have exhibited more of an acute ability of reflecting how photography can reflect our inner psychology—often in ways we are not even fully conscious of.

As many have found before and since, the demands of motherhood took from Mann some of the time she needed to pursue commercial opportunities in photography, as well as the ability to travel freely.

So she decided her practice would become tied to her home — a 400-acre farm she co-owned with her brothers, on the banks of the Maury River and tucked into the Virginia hills. The farm was bucolic, but also remote, "a thing of privacy”.

Blackwater 9, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

For the next decade, her artistic focus became her children. The resulting series, titled Immediate Family published by Aperture in 1992, remains, three decades later, possibly her best-known work.

In a sensual and dramatic monochrome, again exquisitely printed in large format via the wet-plate collodion process, the series depicts Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia, aged six, four and one when she started the project, and 12, ten and seven at the time of the series’ publication.

Mann captured them doing what children do: playing, exploring, climbing, dancing, dressing up as make believe, swimming, quarrelling, crying, eating and sleeping. She photographed them bruised or recovering from insect bites. Mann captured “all of it”, she wrote in the New York Times in 2015. “Out of a conviction that my lens should remain open to the full scope of their childhood.”

Around a quarter of the 60 images Mann published showed her children unclothed, their bodies often holding evidence from their play on the farm. Sometimes, Mann would pose her children, or collaborate with them for staged scenes. Sometimes, these staged images included nudity too.

Within three months of Immediate Family going on sale, its first print run of 10,000 issues sold out. The publisher quickly ordered another round, and the book continues to be traded today, often for significant sums.

Blackwater 15, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Mann’s work was, in many quarters, acclaimed. “The fears and sheltering tenderness that any parent has felt for his or her child were realised with an eidetic clarity,” the New York Times wrote of the series. “The images seemed to speak of a familiar past that was now distant and irretrievable.”

But Mann was also made to endure a highly-wrought backlash she never anticipated. When the Wall Street Journal ran the images, they censored the body of one of Mann’s daughters with thick black boxes. An op-ed ran in the same paper, criticising government subsidies that supported “degenerate” art. Many more puritanical voices in America’s conservative media decried Mann’s images as somehow obscene, suggesting she was sexualising childhood. At one point, a federal prosecutor warned Mann that the images may leave her subject to arrest.

In the New York Times piece, she describes seeing her daughter's body covered in black boxes in the Wall Street Journal as “like a mutilation, not only of the image but also of Virginia herself and of her innocence.”

In a conversation with the artist Jenny Saville, published by Gagosian Gallery in spring 2019, Mann admitted that the scrutiny and whipped-up controversy deeply impacted on her. “But I had removed myself completely from the art world when I was making that work. I was living so far outside of it, I was more or less able to tune out the controversy,” she said.

Blackwater 7, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Yet Mann acknowledges to Saville she feels “it’s a shame that society has a way of inflicting its censorious views."

“When children feel that,” she said, “it gradually undercuts their convictions and confidence. I was lucky because my children were very strong.”

Speaking to Saville, Mann spoke of "a movement that suggests artists who depict suffering in a beautiful or aestheticised way are actually harming the subjects. That it is an ethical violation to make a photograph or a painting of suffering, even if the result is a beautiful work of art.”

Blackwater 30, from the series Blackwater, 2008–12, Tintype © Sally Mann, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Mann was unable to attend the Prix Pictet awards ceremony at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, as she cares for her husband Larry, now suffering from late-onset muscular dystrophy. She often taken portraits of him: “A man as naked and vulnerable, and as beautiful, I assert, as Cupid,” she has written.

Alongside the Prix Pictet garland, Mann is a Guggenheim fellow and a three-time recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. She was named America’s Best Photographer by TIME magazine in 2001.

She remains on the farm by the river, working tirelessly, creating still, the place where she created time-honoured pictures of searing beauty—a process, she says, “as natural as the river itself”.

The Prix Pictet is an annual award celebrating photography and sustainability. Sally Mann was selected from a shortlist of 12 artists, all of whom are being exhibited, and will receive a cash prize of 100,000 Swiss Francs, the equivalent to £82,000.

Prix Pictet: Fire is on show at the V&A until 9 January 2022.