In 1989 Steve Kough, a former National Football League (NFL) player turned drug smuggler, was trafficking electronics from the US into Cuba, and drugs and art back into Miami. The run was financed by the infamous drugs lord Pablo Escobar, but instead of being paid in cash, Kough was given a ceramic work said to be by Picasso, who had apparently given it to Ernest Hemingway.

So goes the far-fetched story told in the podcast Hemingway’s Picasso, co-written by Leah Carroll and Pallavi Kottamasu.

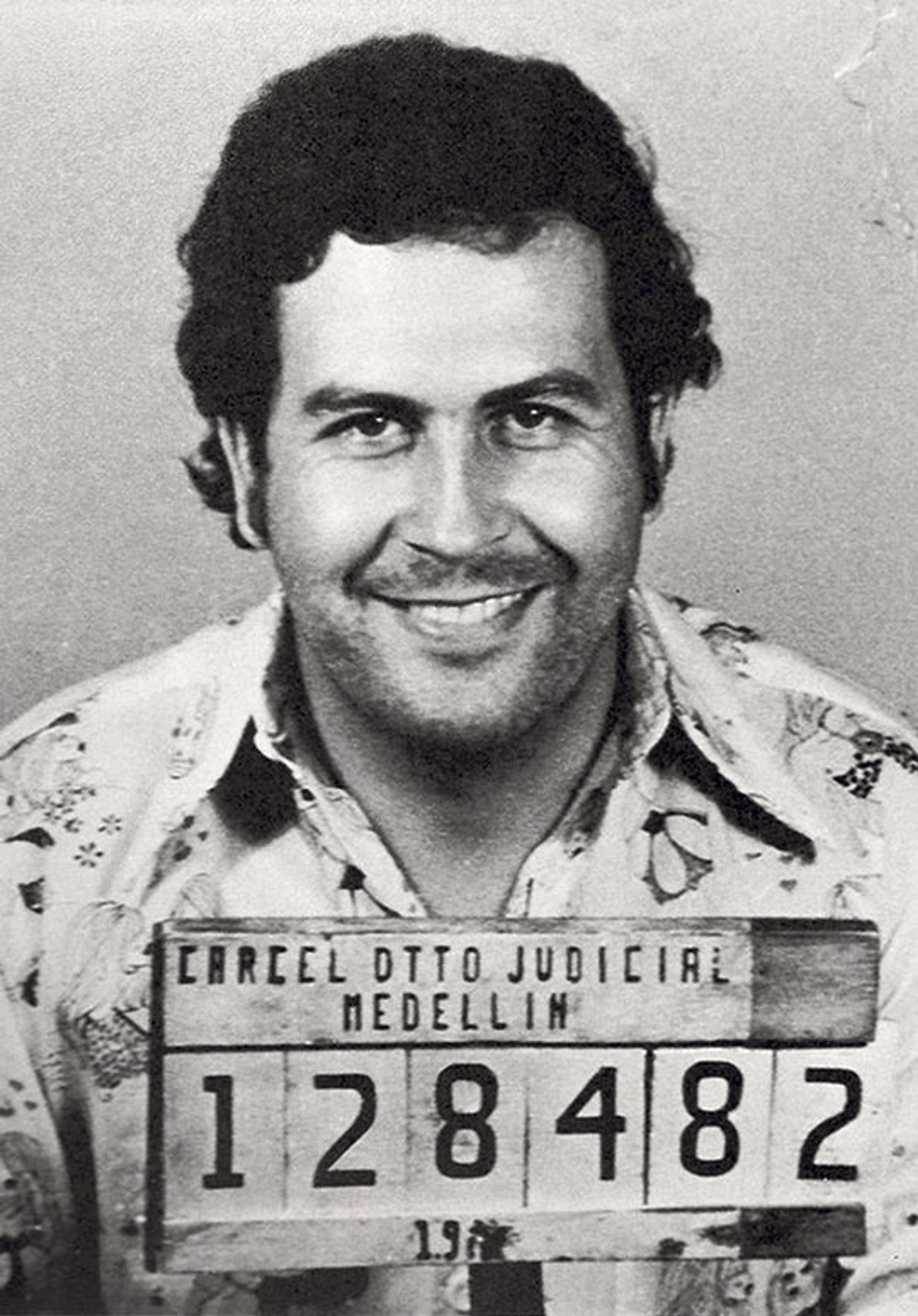

Pablo Escobar was linked to the drugs runner who was given the work Colombian National Police

In recordings made before he died in 2018, Kough claims he was driven to Hemingway’s beloved Finca Vigía just outside Havana, which the writer left in 1960, a year before his suicide. There, Kough is said to have met a curator who handed over the ceramic work, consisting of four tiles that fit together like a puzzle and depict two people, whom Kough called Fred and Betty.

After three decades in his possession, and a thwarted attempt to sell the work at Art Basel in Miami Beach in 2014, Kough passed it to his son Stevie, urging him on his death bed to “get it done—sell Fred and Betty”.

The work, consisting of four tiles that fit together like a puzzle and depict two people, whom Kough called Fred and Betty

Who exactly are Fred and Betty? Contrary to Kough’s assumption that the figure on the right is a man (Kough claimed to have snorted cocaine off what he thought was the figure’s “penis”), Carroll and Kottamasu have established that the figures may be Picasso’s former partner, the artist Françoise Gilot, and their daughter Paloma. Searching the authoritative On-line Picasso Project, Kottamasu came across a 1951 painting, Mère aux Enfants à l’Orange, of Gilot with Paloma and Claude (her son with Picasso). It is strikingly close in style to the ceramic and, significantly, both works prominently feature an orange. But with no established provenance, attempts to authenticate the ceramic via Picasso’s estate have been stonewalled.

Another major piece of the story came with the discovery of a postcard that Picasso allegedly sent to Hemingway in September 1954. At this point, Picasso was living in Vallauris on the Cote d’Azur, where he developed a relationship with the famous Madoura pottery studio. The postcard simply reads: “Para Hemingway, para siempre” (to Hemingway, forever). There is a small drawing of a woman in the top right corner, presumably by Picasso, but there is no postmark on the card, which Carroll suggests could mean it was sent inside a crate—with the ceramic tiles.

Before he died, Kough attempted to establish some sort of provenance, at least trying to prove that Hemingway had once owned the work. For this, he secured video testimony from René Villarreal, Hemingway’s housekeeper whom the writer looked upon as his adopted son. In the video, Villarreal says he recognised the piece immediately, saying that Hemingway often kept it wrapped in a bullfighter’s cloak. Villarreal also signed an affidavit stating he saw Hemingway show it off to multiple people, calling it “my Picasso”.

In a bid to corroborate Villarreal’s account, Carroll tracked down Colette Hemingway, who is married to Ernest’s grandson, Sean. As an art historian, Colette Hemingway has her reservations about the ceramic: “It doesn’t look like anything that I have seen at the Picasso museums,” she says. Nonetheless, she believes Villarreal’s assertion that it was housed in the Finca. Her advice? Take it to Sotheby’s.

It is here the podcast concludes, with an episode (due to air on 6 December) featuring Michelle McMullan, a Christie's specialist who had overseen a sale of Picasso ceramics at the auction house in 2012. Carroll refuses to be drawn on their verdicts, but says: “I came into this 100% believing that not one ounce of the story was true. At this point, I would be equally surprised to find out that the ceramic was a fake as I would be to find out that it’s real.”