In the old world of 2019, the Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, the largest survey of its kind, asked galleries all over the world a question: what are the biggest and most pressing challenges you face?

They responded uniformly. They wanted to increase commerce, find new clients and participate in art fairs. Doing so would be their top priority over the next five years. Environmental sustainability was ranked 14th out of 16 concerns given, while the impact of new technologies ranked as the least important challenge.

How things can change. The global pandemic, which cost millions of lives, made gatherings illegal, postponed exhibitions, closed art galleries and cancelled art fairs, has inverted the industry. It is now widely accepted that the old world’s way of doing things was not just unsustainable—in the arts, and in our broader culture. It was, as the Serpentine Galleries’ Lucia Pietroiusti puts it: “A broken, dying system that was desperately pretending it wasn’t broken and dying."

Suddenly, top gallerists are openly saying the slog from one fair to the next is a relic from a redundant business plan. The weekly flights, the decadent events, the freighting of precious works the world over, the cavernous starchitecture—each belongs to the status quo of another era.

Speaking at Art Basel, Iwan Wirth of Hauser & Wirth told The Art Newspaper: “We plan to be more considered and more strategic.” Dominique Lévy of Lévy Gorvy said: “We will not be going to as many fairs. We’re very clear on that. We were already questioning it before the pandemic.”

Now, new technologies, digital artmaking and sustainable operations are at the top of the agenda for virtually every institution, gallery and fair in the art world, with a new generation of crypto and blockchain artists breaking auction records with the sale of art that does not physically exist.

Pietroiusti works as the strategic consultant for ecology at the Serpentine Galleries in London, a position she took up after working as the museum’s curator of general ecology for three years. She also curated the Golden Lion-winning Lithuanian Pavilion, which focused on climate change, at the Venice Biennale in 2019.

“Art institutions and galleries are facing a number of crises of identity and purpose, and sustainability is one,” she says. “These crises are emerging out of environmental challenges and social justice challenges that are very present. Going back to business as usual is going to sound unconvincing. I can’t imagine why institutions and organisations wouldn’t want to be deeply addressing their sense of purpose in the world as it is today.”

But the pandemic, for all its slow-burn horror, offered a glimpse of an alternative way to function—a new ecosystem in the digital realm that might genuinely be sustainable, and has the capacity to dramatically lower the carbon footprint of an industry widely associated with splurge, wealth and waste. Of the 365 global art fairs planned in 2020, 61% were cancelled. But the majority (62%) offered an online viewing room or digital version of their fair in 2020. And many collectors demonstrated themselves willing to buy art via jpeg, without ever having seen it in the flesh.

The pandemic, then, proved that art can be made, shared, experienced and traded digitally while costing us far less in terms of carbon footprint. And so it created a potential new pathway, in which the art world moves out of the physical world to the virtual, powered by a generation raised online, rather than in art galleries.

Peter Chater, the founder and chief executive of Artlogic, the company that developed a carbon calculator employed by the charity Gallery Climate Coalition, writes: “In comparison with flights and shipping, a typical art gallery’s digital carbon footprint is tiny.” As for digital art, which is often held on websites and is transportable via cloud computing, “the amount of energy used to serve web pages is tiny. Efficient web servers are capable of serving hundreds of pages a second and the total energy consumption of a server will have a finite maximum not dissimilar to a fancy laptop.”

Nevertheless, the environmental costs of digital art are poised to rise exponentially. And that is largely to do with the earthquake known as non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which employ similar blockchain technology to cryptocurrencies.

Buying or minting an NFT relies on a range of complex computational manoeuvres, burning through tremendous amounts of energy. Digiconomist estimates that a single transaction on Ethereum, one of the most high-profile open-source blockchains, has a carbon footprint at 33.4kg of CO2.

Bitcoin, the world’s most-used cryptocurrency ,“requires a vast amount of electricity”, Chater writes. “Bitcoin is run by over a million individuals, oftentimes at the scale of whole data centres built for this purpose, leading to a morally unsupportable outcome,” he says. Chater notes that, as a company, Bitcoin has a larger footprint than the state of Argentina, while the Guardian estimated that the sale of 303 editions of Grimes’s Earth NFT, which involved Bitcoin, “used the same electrical power as the average EU resident would in 33 years.”

While emerging blockchain platforms, like Palm, claim that they will in the near future be able to decrease the carbon costs of mining and minting by 99.9%, it is clear that the jury remains out on blockchain technology’s carbon footprint.

Artists, not companies

“NFTs will, in my opinion, be short-lived,” Pietroiusti says. “It seems to be an easily combustible moment. Very clearly, there’s an unrealistic relationship between NFTs and the energy it takes to run them.”

The answer, Pietroiusti suggests, lies not in companies, but in the work of pioneering artists. “There are visionary and engaged practitioners with a strong commitment to environmental and social justice,” she says. “They are the ones figuring out how to deploy digital in a way that works, that makes sense, and that reaches people.”

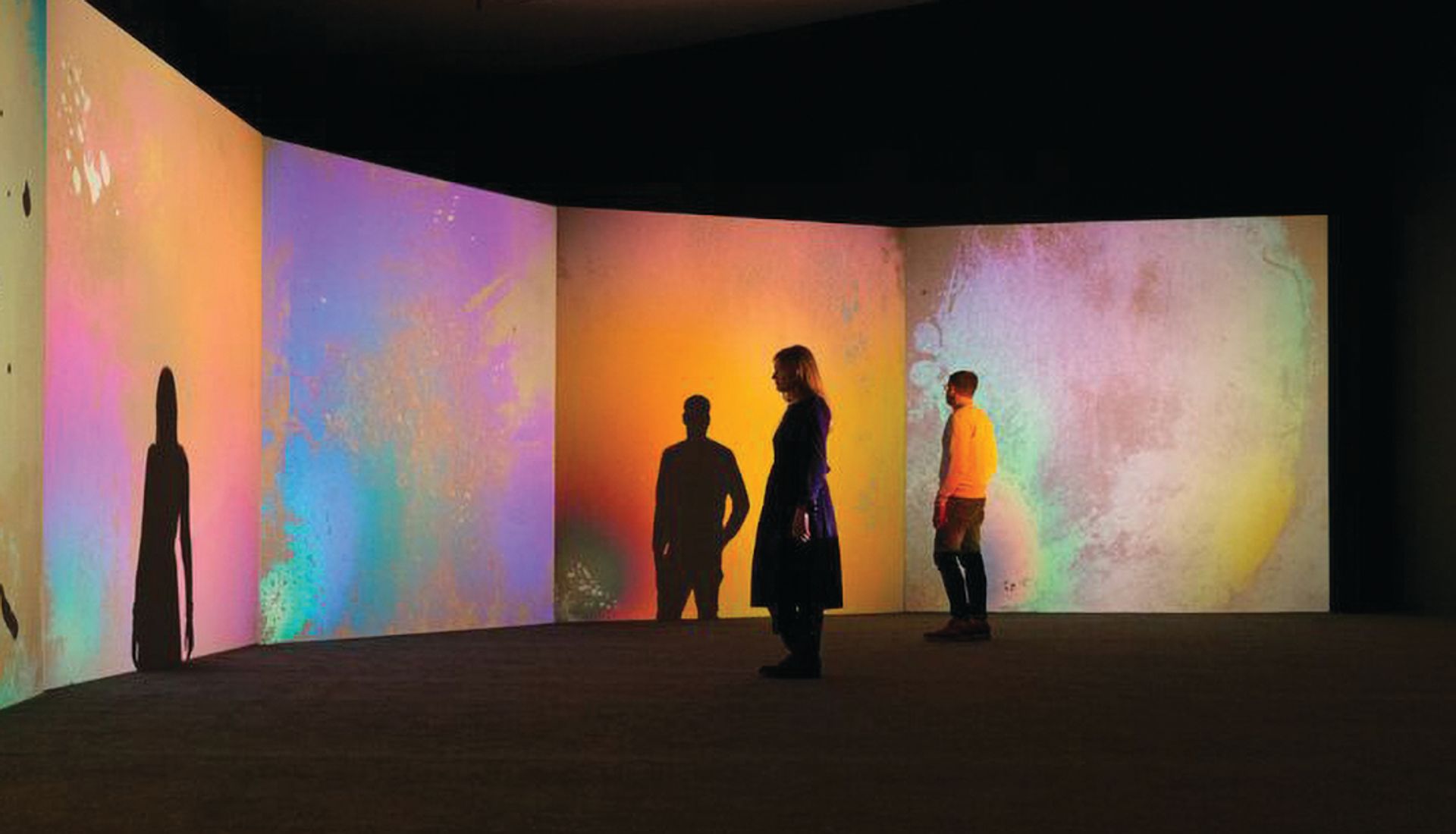

A godfather of this movement might be Gustav Metzger, the late and lifelong environmental activist whose estate is represented by Hauser & Wirth. Cliodhna Murphy was recently appointed the gallery’s first global head of environmental sustainability; she worked closely on the Metzger exhibition, Liquid Crystal Environment, at Hauser & Wirth Somerset last summer—an “auto-destructive” form of art designed to instigate social change.

The Metzger show, an early digital installation, was the first time a Hauser & Wirth exhibition devised a comprehensive carbon budget, a metric developed alongside the Carbon Accounting Company.

“From a practical standpoint, we looked at the infrastructure around the exhibition and considered the life cycle of each of the materials used,” Murphy says. “That’s a key element of digital art that’s often missed: the furniture, the wall space, the curtains, the projector. If you consider the life cycle of each, you can develop a circular economy around them, rather than allow them to end up in landfill after a digital exhibition.”

A top-tier gallery the size and scope of Hauser & Wirth is still at the early stages of working out how to be sustainable, Murphy admits. “We’re the first gallery to have hired someone in my position, and we’re learning as we go,” she says. Hauser & Wirth is now planning on implementing carbon budgets for each exhibition from 2022 onwards, be it digital or not.

For its recent exhibition of works by the late artist and environmental activist Gustav Metzger, Hauser & Wirth devised its first carbon budget. Photo: Ken Adlard; ©The Estate of Gustav Metzger and The Gustav Metzger Foundation; Hauser & Wirth Somerset

Another such artist might be Pace-represented John Gerrard, who is currently exhibiting two digital sculptures, Mirror Pavilion and Leaf Work, powered by biofuel and situated amidst the elements at the Galway International Arts Festival.

“The digital will be a major part of artistic expression into the future,” Gerrard says. “In terms of art and activism, digital offers many new ways to speak at scale about ecological subjects in the public domain.”

But how to make a work about climate activism without creating high levels of emissions? “The challenge is to find ways to use less carbon-intensive methods to power the work in a remote setting,” Gerrard says. “For Leaf Work, we used biogas to power the work in the remote landscapes around Galway. The work itself performs a lament for a heating world.”

This is perhaps the crux. While the art world grapples with the cost of creating and showing digital and physical art, it still maintains the potential to reach and activate people far beyond the gallery space.

As Catherine Bottrill, the author of a recent Julie's Bicycle report on the art world’s impact on the environment, writes: “The ace card of the visual arts is its capacity to mobilise climate action. To meet this potential, art and artists need to be supported by all parts of the community.”

Pietroiusti agrees. “That’s the weird thing about art: never assume it doesn’t work. There are no human metrics for measuring the impact of art. Yet art persists throughout time. Shifts have happened and can happen. It’s just a case of imagination.”