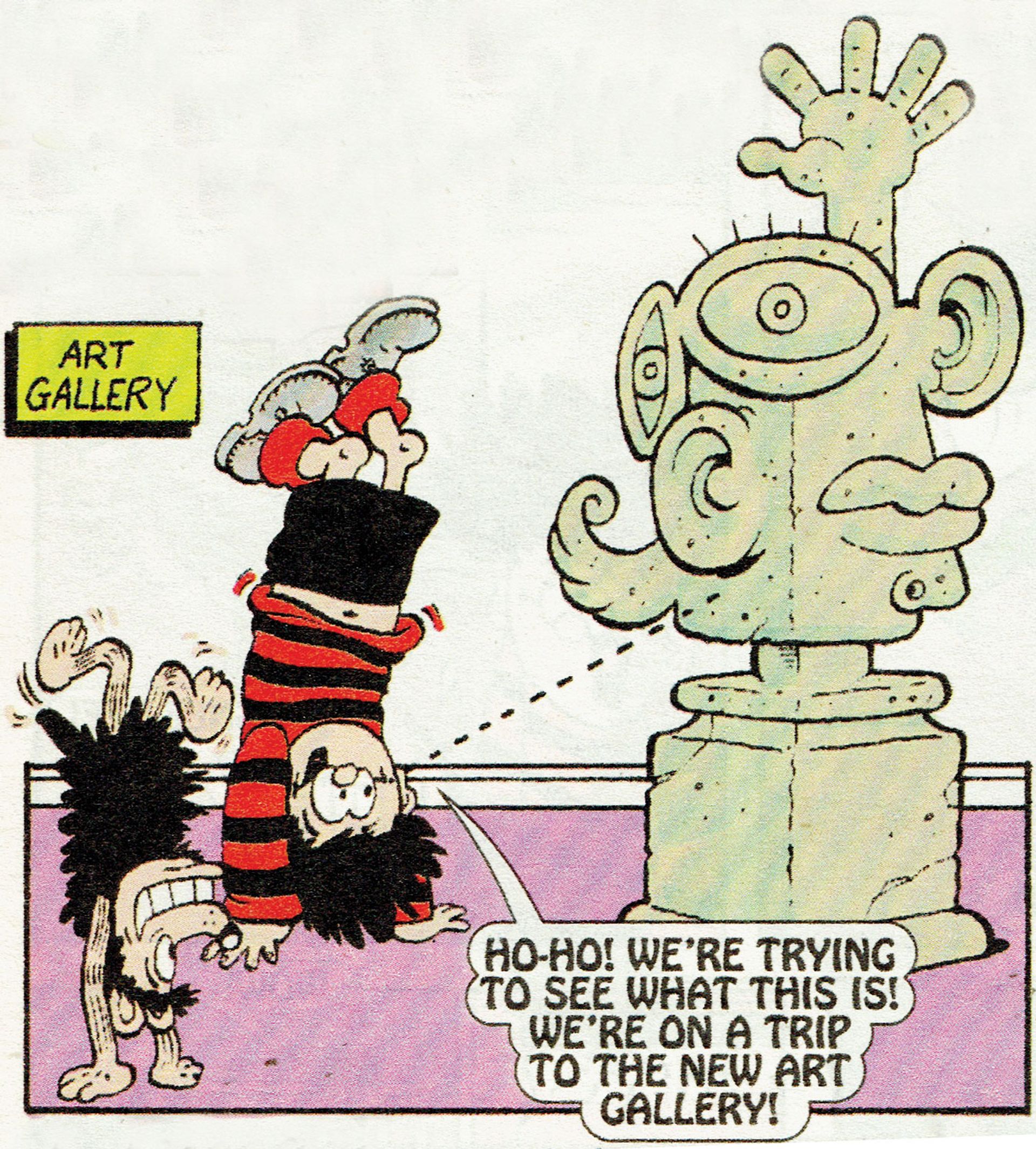

The Beano is the longest running comic in the world and its cast of mischievous characters like Dennis the Menace, Minnie the Minx and the Bash Street Kids—with their hijinks and disdain for authority—have delighted children and adults for generations. The British publication is still based in Dundee, where it was first published in 1938, and now, after more than 4,000 issues, its history and enduring impact on visual culture will be explored in a new show of contemporary art at London’s Somerset House.

“The Beano has this great reflexivity where it pretends that the Beano is made in the Beano”

Visitors will be immersed in a Beano world with life-sized backdrops and characters popping up to guide the way. The exhibition’s curator, the artist Andy Holden, thinks that the Beano has had “a kind of subconscious influence” on British art and culture, and aims to highlight this with a selection of 52 artists—including those below—who have either been directly influenced by the comic or exhibit a “Beano sensibility” in their work.

Mark McGowan, Margate Beach (2008) Courtesy of the artist

As an example of this sensibility, Holden mentions the performance art of Mark McGowan, who once cartwheeled from Brighton to London, as embodying the irreverence and silliness of a Beano character. There will be new commissions, including a new comic strip of Dennis the Menace as an old man by Nicola Lane and a two-way mirror sculpture by Simeon Barclay inspired by the Bash Street Kids character, Plug.

The show has been organised in conjunction with the Beano and for fans of the comic there will be a “pretty scholarly history” of the publication, Holden says. “As a kid, I don’t think I really thought about the people who drew these or the idea that it was even drawn,” Holden says. “The Beano has this great reflexivity where it pretends that the Beano is made in the Beano.” The exhibition will delve into the drawings by some of the comic’s key cartoonists, from pioneers like Leo Baxendale, who created Minnie the Minx, to Laura Howell, who draws the character today.

Dennis and Gnasher (2000) Artwork by David Parkins. Courtesy of Beano

Holden says that although he was a “dedicated reader” as a child, who loved drawing the comic’s characters, he had never thought of the Beano as an obvious artistic influence on his work. Now, however, he sees its visual culture and “joyous rebellion” as one of the bedrocks of British culture. “It’s a playful British sensibility that the Beano absolutely encapsulates,” he says, adding that he hopes the exhibition, much like the comic, will act as a “gateway to art and culture” for visitors young and old.

How did the Beano influence you as an artist?

Holly Hendry

Holly Hendry

“Until being part of this show, I had never made a connection between reading the Beano as a child and what influence that had on me—which feels obvious now I think about it. There are so many aspects: the flatness of the characters’ full-on actions; settings that illustrate entire systems; things going wrong or clumsy blunders; plasmatic stretches, slops and bulges, and extreme excess—food, movement, matter. Leo Baxendale’s illustrations are the best examples of breaking the rules done right. His limited colour palette and graphic lines are clever aesthetic tools. He managed to slop on layers of action and chaos while simultaneously including vital detail and specific moments, and that detail is something I feel a definite affinity with, and aspiration towards.”

Emma Hart

Emma Hart

“The Beano was probably the first thing that no one told me to read. My mum hadn’t read it and didn’t read it, and so she didn’t have an opinion on it. Because of this, it created a kind of unique space for me growing up that was just for me. It didn’t bring with it any pressure or expectation and I loved the stripes, the bold colours and the punk aesthetics. The Beano was my first introduction to something being self-referential; I vividly remember characters threatening to punch each other into next week’s comic. I think that opened up a new world of creative possibilities for me.”

Matt Copson Photo: © Mark Blower

Matt Copson

“I read the Beano every week as a kid and was a fully conscripted member of the Beano Club. I really wanted to be Dennis and would live vicariously through his softcore rebellion. I used to draw Dennis a lot; the lines that make up his face were probably my first introduction to making art. I remember enjoying drawing his hair and, looking back at it, that makes sense: it’s the greatest part of his design, and a wild abstract form itself. Comics will always be avant-garde because they remain a dismissed art form and that’s a reason alone to value them highly. I really enjoy the crude simplicity and blunt directness of comics as a way of dismantling archetypes and cliches; it strikes me as a truthful way of grappling with a cartoonish world.”

Nicola Lane

Nicola Lane

“I was born in San Francisco and lived in seven countries before the age of 16. At five, I met a British boy of the same age when I was living in Bangkok and he showed me his copy of the Beano. This was not the clean, cute, pastel-coloured world of the American Dell Comics I was used to, like Woody Woodpecker and Donald Duck. The crude and lively drawing, the characters—these were exciting creatures from another world.”

Simeon Barclay Courtesy of the artist and Workplace

Simeon Barclay

“My early inclination to draw was the urge to mimic and copy the illustrations in the pages of those British comics like the Beano, the Dandy and Whizzer and Chips. It was a space of comedy, kinship, solitude, escapism. There is a revelry within the space of the frames for anarchy and turning conventions upside down, so there is an element of [the Russian philosopher Mikhail] Bakhtin and the carnivalesque—a sort of release for the viewer. I loved the Bash Street Kids character, Plug; I claimed him as a leitmotif in my work, his innate ugliness placing him on the fringe of society. A mirror to society’s normative tropes, he stands proud in the liminal space where his mere presence enacts a criticality. It’s a shame but in the absence of any relatable or expansive Black characters at the time, Plug’s bonkers individuality, for me, opened up an unorthodox and contingent space in which to insert and mirror myself within the frame.”

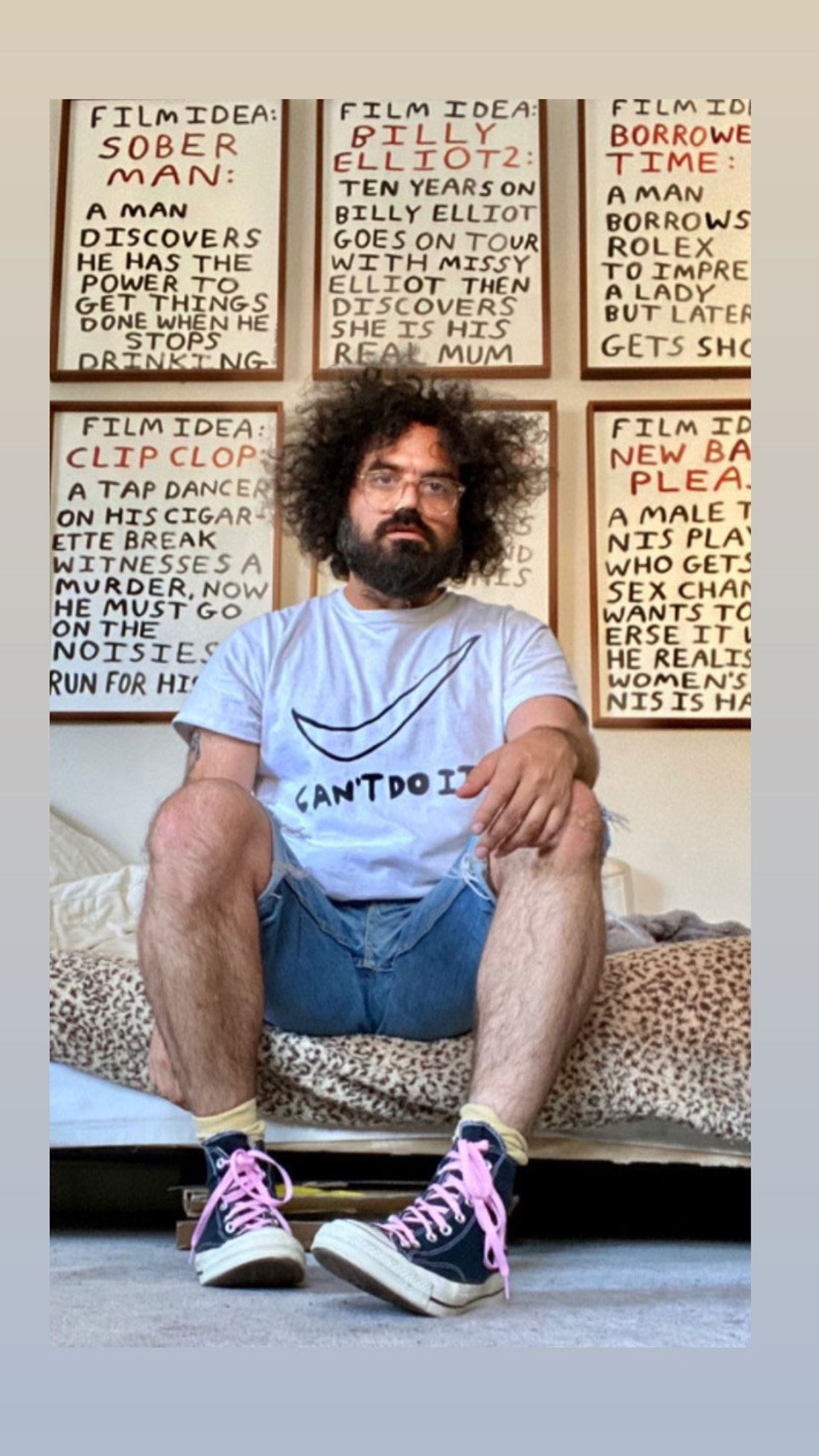

Babak Ganjei

Babak Ganjei

“I write autobiographical comics and for a few years it was all I was doing. Those years I think contributed greatly to my practice in multiple ways—to learn to communicate with efficiency, each panel containing just enough visual information to move the message across. The same goes with pacing. It can also be an incredibly effective way of being open, honest and vulnerable while hiding behind a character, even when that character is you.”

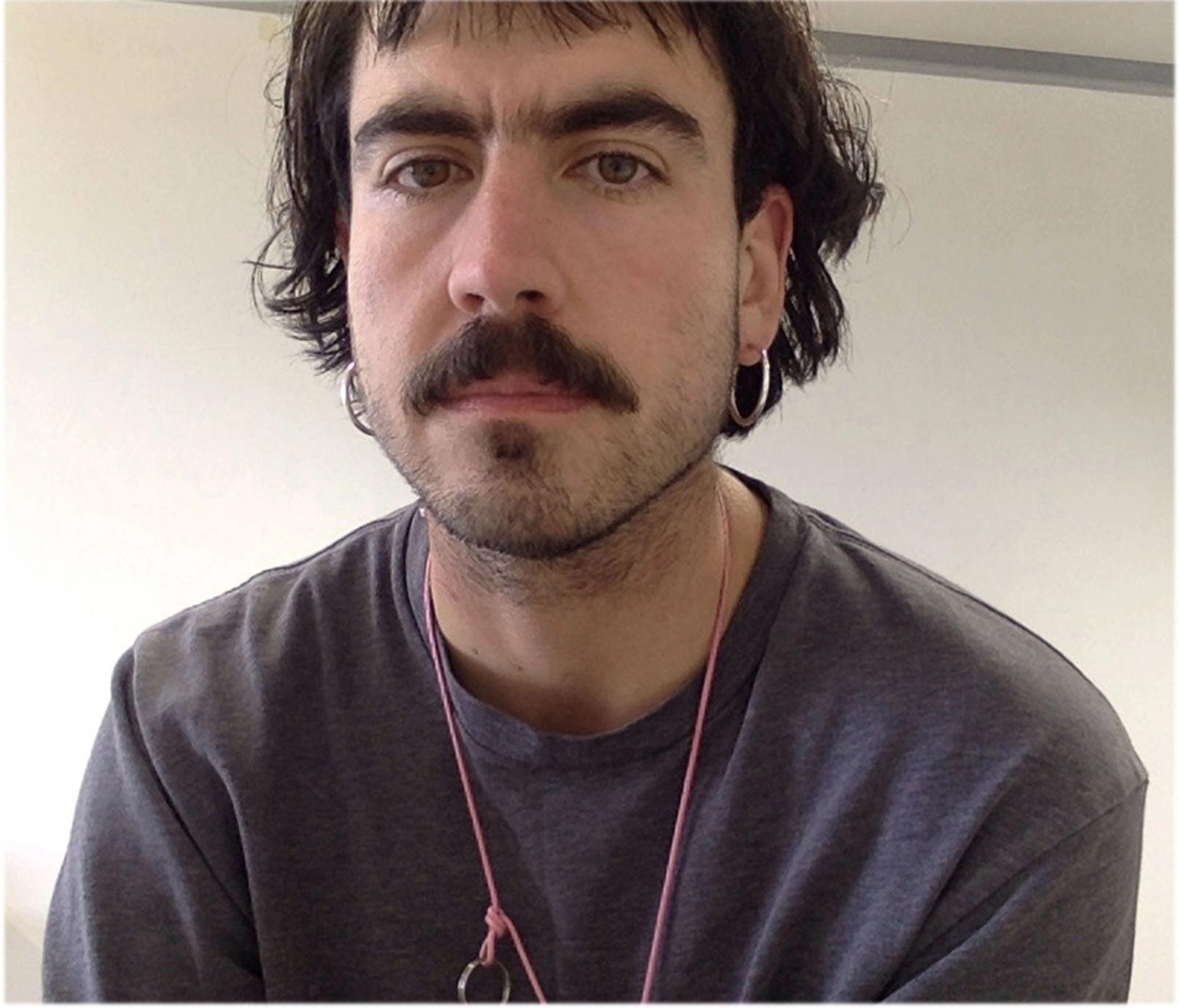

Flo Brooks

Flo Brooks

“We had some of the Beano annuals at home and I used to devour them at night for years, going back to my favourite strips and characters. I identified most strongly with Les Pretend—a true queer icon. For years, I never knew whether Les was a girl or a boy; I think I recognised that Les lived very much in another world, and that chimed with how I felt in mine at the time, especially with other girls my age—alien to them, wanting to get out and feeling desperately stuck somehow. I had those kinds of intense, melodramatic relationships with characters in books and comics as a young person, obsessively living through them, creating these epic narratives in my head.”

Bedwyr Williams

Bedwyr Williams

“I loved the Beano as a comic but I kind of loved it as an object, too. I liked finding old ones and re-reading, lying on the floor wherever I’d found them. Now, I think about those moments when things go wrong for a character and they are humiliated in the last frame. Meeting clever artists and curators in some awful situation like [the art fairs] Art Basel or Frieze feels like that.”

• Beano: the Art of Breaking the Rules, Somerset House, London, 21 October-6 March 2022