During the last two weeks of August, as the Taliban retook Afghanistan and closed in on the capital, Kabul, the US military raced to evacuate troops, American citizens and Afghans who had acted as interpreters for battalions and civilian contractors. Staff at the US embassy were quickly relocated to makeshift but secure facilities at Hamid Karzai International Airport, and more than 125,000 people were flown out by end of the month. However, many were left behind, raising ongoing concerns for the US State Department and Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who has been grilled by House and Senate committees about the chaotic evacuation.

One issue that was worked out ahead of time, however, was the removal of a large collection of art from the US embassy. According to a spokesperson for the State Department: “We have confirmed that pieces of art were packed up and shipped before embassy operations shifted to the Kabul airport. These items have arrived in the United States and are in the process of being reviewed and inventoried.” The exact number of works was not revealed, but the paintings, photographs, sculpture and drawings in the collection had all been purchased by the US State Department through the agency’s Art in Embassies programme.

Works by more than a dozen artists were installed at the Kabul embassy, and many of them expressed concern to The Art Newspaper about the fate of their art if the building was taken over by the Taliban, although all placed the need to protect human lives above their works. State Department staff had been advised to destroy any documents and materials left behind that could be used in propaganda by the extremist organisation, such as flags or images of US leaders.

Pat Lipsky, Builder (1999) Courtesy the artist

New York-based artist Pat Lipsky, whose oil-and-acrylic painting Builder (1999) was bought by the State Department in 2015, says that she had worried “that the Taliban would walk into that room and see that abstract painting, and then destroy it”. Lipsky and Camille Benton, the curator of the Art in Embassies programme, had exchanged emails in the previous few weeks, with Benton noting that the government was more worried about getting people out of Afghanistan, and she told the artist that she would be in touch when she had more information to share. “Of course, the evacuation of people is tremendously more important,” Lipsky says.

“Human life is the top priority,” agreed the Toronto-based artist Erica Gajewski, whose three drawings of animals were acquired by the State Department for the site in 2017. “I hope to see them again at some point.”

Erica Gajewski, Kabul Markhor (2017) Courtesy the artist

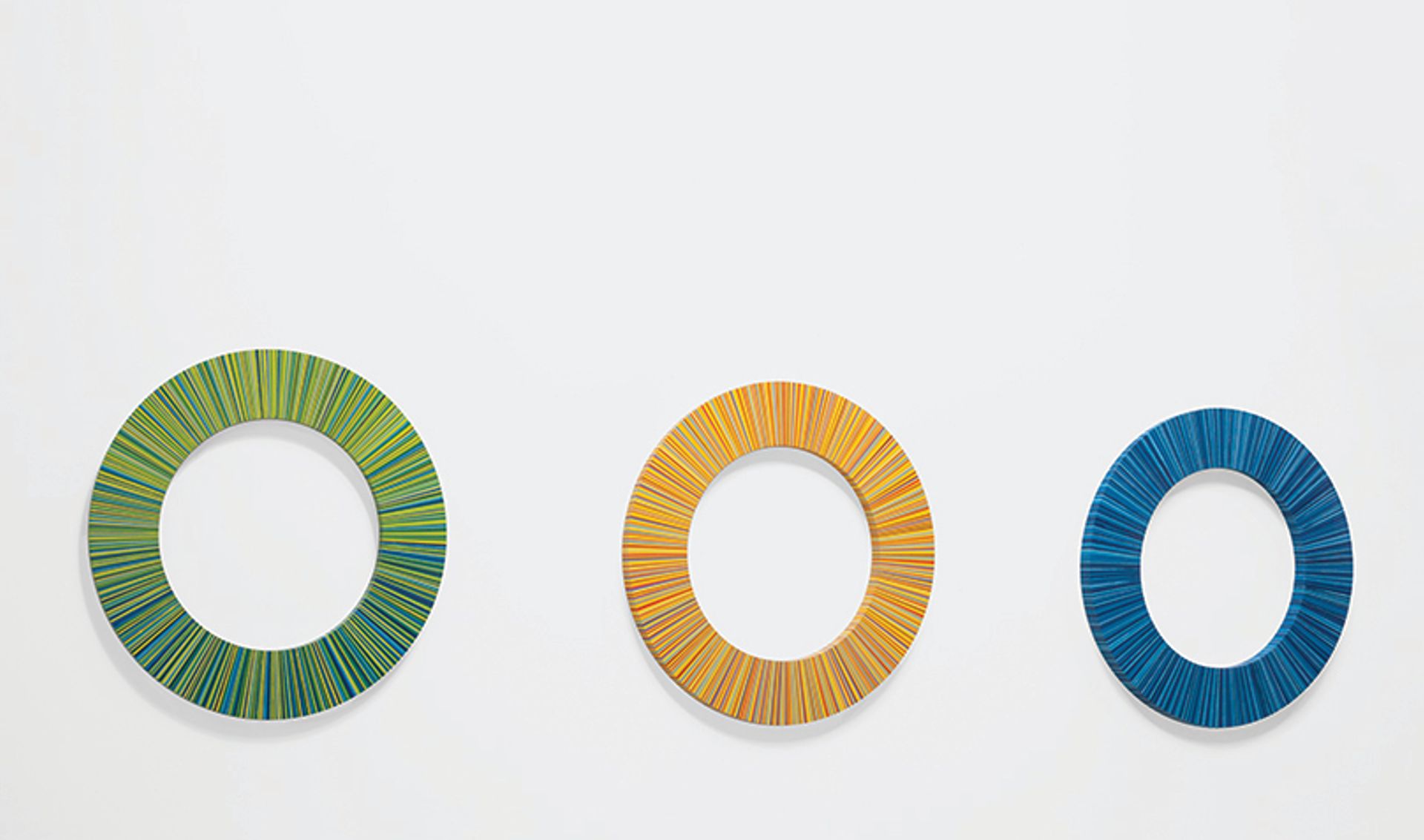

The Los Angeles-based textile artist Lisa Anne Auerbach had a carpet installed in the embassy that she produced during a group visit to Afghanistan in 2014, while the New York-based artist Judy Pfaff’s mixed-media piece New Morning (2009), had been bought by the State Department through her gallery Ameringer McEnery Yohe (now Miles McEnergy Gallery) in 2014. But Pfaff “wasn’t even aware that the work was in Kabul”, according to her studio administrator Edward Stapley-Brown. And the Berkeley, California-based artist Peter Wegner had three gloss alkyd enamel on panel works on display, Color Wheel 3, Color Wheel 4 and Color Wheel 6 (all 2015). “I’m not concerned that the Taliban will destroy my paintings—I’m concerned they’ll destroy Afghanistan,” Wegner says.

These works were all specifically acquired for the Kabul embassy, which was built in 2013, replacing a less well fortified one that had been repeatedly attacked by the Taliban and other insurgent groups. The new building, which occupies a 15-acre site two miles from the city centre, cost more than $800m, and includes a dozen different structures (including offices, a residential complex, Marine Security Guard quarters, a warehouse, and water and sewage treatment plants). The typical art budget for such large-scale capital projects, such as the building of a new embassy, is 0.5% of the construction costs, although the State Department has not confirmed how much money was spent on art acquisitions for the embassy in Kabul.

Peter Wegner, Color Wheel 3, Color Wheel 4 and Color Wheel 6 (all 2015) Courtesy the artist

For most of the 50 years that the Art in Embassies programme has been running, works have been borrowed directly from artists or through their galleries for displays that last several years at most. Artists are invited to submit images for possible loans through the State Department’s website, and the programme even rents a stand at the annual College Art Association conference in order to spread the word. But in 2005, the programme also began purchasing pieces for its collection. Roughly 10,000 works are in the care of the programme at any one time.

The Art in Embassies agency is relatively small, with a budget of $1.8m and a staff of one director, three full-time registrars, a few administrative staff and six full-time curators, whose job it is to provide work for, and organise exhibitions at, the 200 or so American embassies around the world.

To assemble an embassy collection, the curators present an array of examples by a variety of artists on a particular theme—for instance, women or Latino artists or those whose work has been influenced by a certain culture, or artists from the ambassador’s home state—and the ambassador makes a final selection. Cultural sensitivity matters, as art that fits perfectly in an American art gallery may breach cultural taboos in other countries. Nudes are not allowed in the Middle East, for example, and a painting with a depiction of the Buddha’s head was not permitted in India, because the Buddha must always be represented with a full body.

The Kabul embassy included a work by an Afghan artist as well, a large-scale wind-powered object that can find and detonate unexploded land mines, by Massoud Hassani. The work was also acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York for its design collection.