In an audio clip at its website, the Metropolitan Museum of Art describes it as “the best Neo-Classical portrait in the world”: a 1788 oil by Jacques-Louis David depicting the so-called father of modern chemistry and his wife with scientific instruments in their Paris office.

Today the Met announced that its own scientific research had yielded surprising insights into the nine-foot-tall double portrait, Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (1758–1836). Rather than portraying the Lavoisiers as a scientifically minded couple embodying Enlightenment ideals, as they appear in the final version, the museum says, David originally depicted them as fashionable members of the French elite.

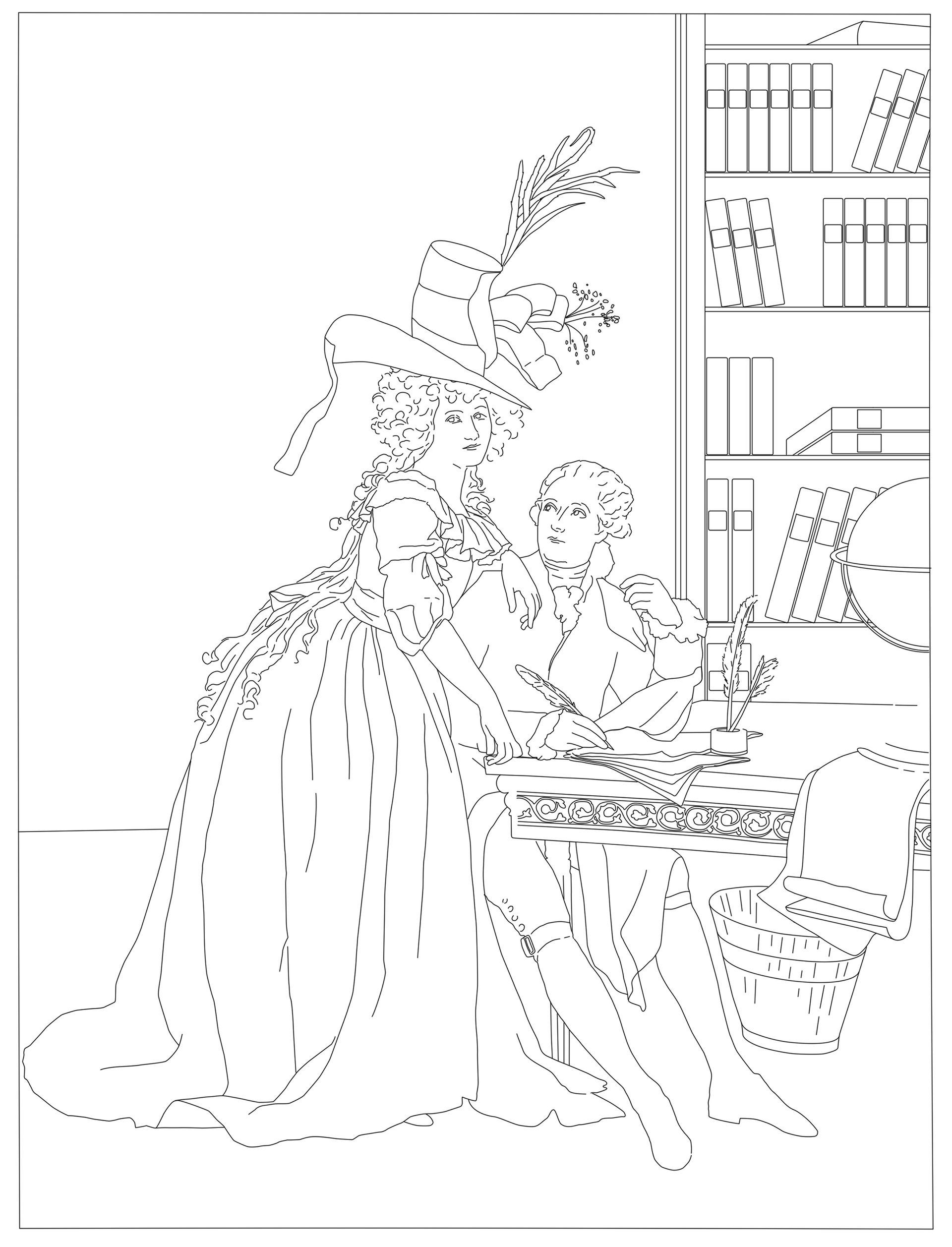

An analysis of the mammoth canvas with noninvasive infrared reflectography and with macro X-ray fluorescence mapping, a technology that did not exist when the Met acquired the painting in 1977, revealed a fully painted underlayer detailing David’s initial conception. It features an ornate desk with an ormolu frieze, three scrolls of paper unfurled over the edge of the desk that reflect Antoine Laurent Lavoisier’s privileged position as a tax collector, and ostentatious attire for Mme Lavoisier, who sports a giant plumed hat adorned with ribbons and artificial flowers. Missing in that composition is the chemistry equipment, including a glass balloon and beakers.

A drawing produced with tracing information obtained through infrared reflectography and macro X-ray fluorescence. It reflects Jacques-Louis David's original rendering of Antoine Laurent and Marie-Anne Lavoisier in a 1788 portrait. Department of Paintings Conservation, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Originally published by The Burlington Magazine

This original vision of the couple, with an emphasis on their affluence, underlines the fate that awaited Antoine Laurent Lavoisier. His role as a tax collector not only bankrolled his discovery of oxygen and the chemical composition of water, but ultimately helped lead to his execution by guillotine in 1794 during the revolutionary Reign of Terror. Marie Anne Lavoisier, who helped publicise her spouse’s scientific achievements with drawings and engravings and is thought to have possibly been an art student of David’s, survived.

“I think the very tempting theory is to line it up with the politics and say, 'Oh, they wanted to move themselves away from looking like the tax collector class,'” says David Pullins, associate curator of European paintings at the Met, who carried out an art historical analysis of David's changes in the painting. “They were very intelligent, thoughtful people.”

Still, any impulse to view the compositional changes through the lens of the Revolution could be a stretch, Pullins said in an interview. “I think it’s difficult to push it that far,” he says. David “was a remarkable chameleon,” he notes, continually evolving, and the painting is “an exemplar” of that.

He suggests that the artist’s first rendering was influenced by the increasingly informal portraits of “blue-blood” aristocrats in the 1770s and 80s by leading women painters such as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adelaïde Labille-Guiard. David and the Lavoisiers may have later reconsidered the initial portrayal, given the couple's own limited social standing, the curator adds.

“It was a format that would have been very easy to paint Marie Antoinette in, and of course, Vigée Le Brun does that,” Pullins says. “But for a couple like this, that doesn't even have a title?”

A mapping of hidden paints consisting of lead (in white) and mercury (in red) revealed through macro X-ray fluorescence testing Department of Scientific Research and Department of Paintings Conservation, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Originally published by S.A. Centeno, D. Mahon, F. Carò and D. Pullins, Heritage Science (Springer Open), 2021

David’s final choice to highlight the Lavoisiers’ scientific bonafides, and eliminate the showier attire, may also have been inspired by an instinct to depart from familiar models of portraiture and “create a new kind of image”, Pullins says–which is “why the painting as it exists now looks like a shock, why it looks as much of a landmark, as it is. This was by no means a conventional or obvious kind of image for people of their station, to foreground science in this way.”

The Met’s announcement was timed to the release of scholarly articles about the discovery in The Burlington Magazine and Heritage Science authored by Pullins, Silvia Centeno, a research scientist at the museum, and Dorothy Mahon, a Met conservator. The Met research scientist Federico Carò also contributed to the Heritage Science article.

The scientific testing began in 2019 after Mahon spent ten months removing a synthetic varnish that had been thickly applied to the canvas in 1974 and had given it a milky grey appearance. After painstakingly stripping the varnish, she observed irregularities in areas of the painting that suggested that other features might exist just below the surface, which led to the extensive tests. “The first thing we did was the infrared, and we knew there was more there,” Mahon says.

Centeno later proceeded with the macro X-ray mapping, which allows scientists to determine the mineral composition of different layers of a painting–a technology that she says the Met purchased only five years ago. Tiny pigment samples were also taken from the canvas to shed more light on the mapping, she says. The chips confirmed the red and black hues of Marie Anne Lavoisier's striking plumed hat. They also showed that in his first iteration, David painted Antoine Laurent Lavoisier in a brown costume with a longer coat adorned by seven bronze-coloured buttons, unlike the black coat with just three buttons and black breeches that are visible today.

As Mahon puts it, David ultimately chose to make the scientist's ensemble “more like a business suit”.

Silvia Centeno, at right, generating X-ray fluorescence maps of Jacques-Louis David's portrait of the Lavoisiers Dorothy Mahon, 2019

The early version had even topped Lavoisier’s ensemble with a flowing red mantle, “a shocker” that was “really baroque, almost archaic”, Pullins says. That also fell by the wayside. Among the other elements eliminated were a bookcase in the background that Mahon says would have warred with the addition of the “clear and beautifully painted” scientific instruments, and a wastebasket. The placement of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier’s leg was also adjusted. And the addition of a red velvet tablecloth in the final iteration was “a great solution for canceling over all that stuff” that the artist discarded, she adds.

“Until recently, revealing compositions hidden below a painting’s surface with such a level of detail would have been impossible,” notes Centeno.

Centeno, Mahon and Pullins describe their research effort and newly published scholarly articles as a model of collaboration among professionals with markedly different expertise. The initiative echoes joint projects in recent years by art historians, conservators and research scientists at the National Gallery in London and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Going forward, the Met hopes to expand collaborative investigations that keep essential works alive for the scholarly community and for visitors. “It’s lived here since the 1970s and, yet, it’s had this life that kind of kept on giving,” Pullins said of the Lavoisiers’ portrait. “It's the opposite of a story of a painting going into a museum to be kind of locked away and put in a tomb.”

The portrait is currently on view in the museum’s second-floor Neo-Classical galleries.

For Mahon, the work's enduring relevance is rooted in its emotional appeal. “He looks up to her with such devotion, and she looks out at us,” the conservator says of Lavoisier. "I think he [David] knew what he was doing, and whether they are of this time or not, the couple had that same sensibility that we really relate to today.”

Jacques-Louis David's portrait of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and Marie Anne Lavoisier, being reinstalled in the Met's galleries last November Eddie Knox © Oxford Films, 2020