The British artist Damien Hirst laid off 63 people in one of his studios last October, while he claimed £15m in emergency Covid-19 loans from the UK government, as well as using the furlough scheme.

Former employees in Dudbridge, Gloucestershire, say they were first alerted to plans to cut jobs in April 2020, shortly after the UK entered its first lockdown of the pandemic. Several weeks earlier, they had been informed that a major retrospective of Hirst’s work, which had been due to open at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing last year, had been cancelled.

From then on, Hirst sought to remodel his business, pausing the production of new works (apart from proven best-sellers such as pill cabinets with white pills), prioritising the sale of existing pieces and drastically reducing the number of roles at Science (UK), the firm which manufactures Hirst’s art. The redundancies represented more than a third of Hirst's overall workforce and the majority of those based in Dudbridge.

Hirst declined to comment for this article.

Consultation period

The Dudbridge redundancies were made after a series of consultations with staff over a two-month period beginning on 5 May 2020. The purpose of the meetings, which were attended by a representative from the law firm Joseph Hage Aaronson, was to explore ways to avoid or reduce the number of redundancies and mitigate the effects of any dismissals. Under UK law, a collective consultation must take place if a firm wishes to make 20 or more employees redundant within 90 days.

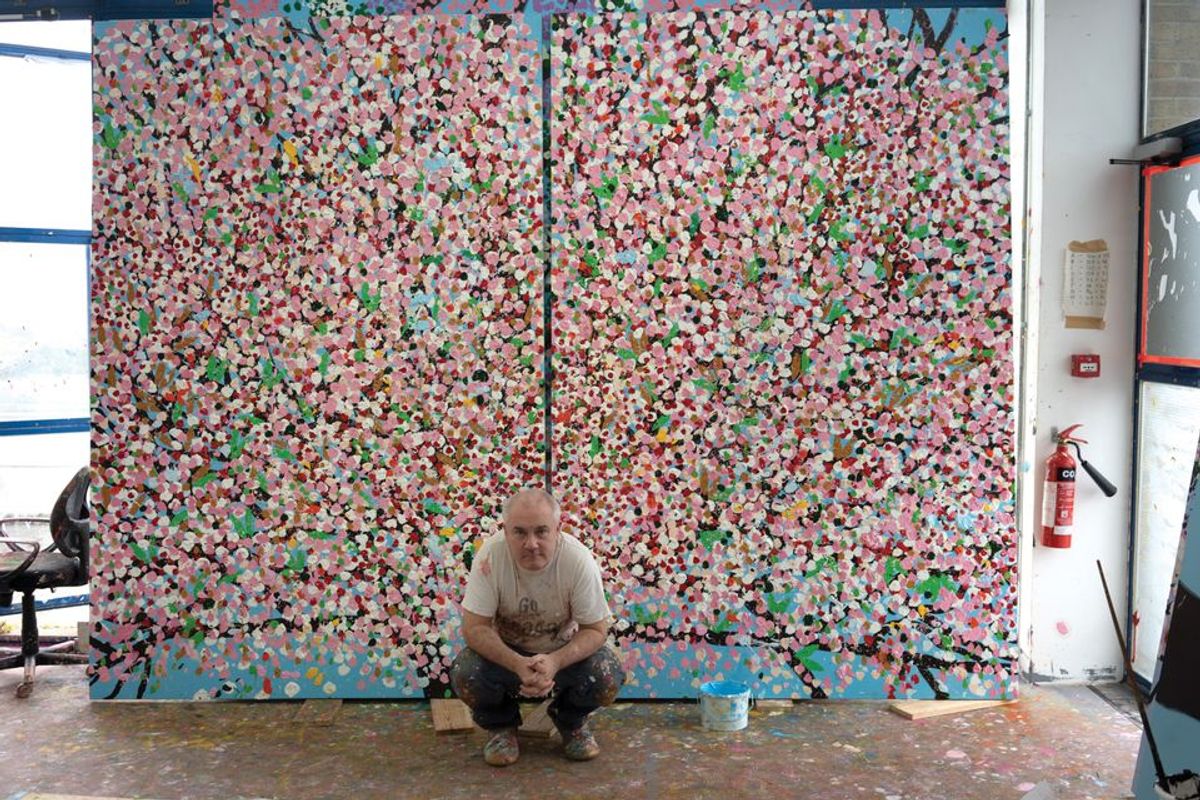

Known for employing large teams of assistants to produce his art, former staff in Dudbridge say they were told in the first consultation meeting that only Hirst was creating work at the moment. The vast majority of the 3D and painting teams in Dudbridge were subsequently let go, while there were further redundancies in the administrative department. Cleaning and health and safety staff were also laid off and the warehouse was reduced to a skeleton operation.

Staff were scored on a “matrix” to help determine who should keep their job. Criteria ranged from a proficiency in Adobe, attendance and first aid training through to the right attitude, flexibility and the ability to learn. According to representatives from Science (UK), the skills listed on the matrix met current business needs, including, for example, a knowledge of how to manufacture and restore formaldehyde and resin works, experience chiefly held by the management team.

While the production of new work was ostensibly suspended, Hirst’s latest accounts show that Science (UK) owns £42.7m-worth of unsold art. His art collection, meanwhile, formerly known as Murderme but renamed Prints and Editions in January 2020, is currently worth £183m.

Both Science (UK) and Prints and Editions were among the “Science group” of businesses to receive the three-year £15m large business interruption loan from the government in October. Both are subsidiaries of Science, which is based in the offshore jurisdiction of Jersey and is the main purchaser of Hirst’s art. In addition, Science (UK) owes more than £100m to its offshore parent company.

Works from Hirst's Venice exhibition Treasures of the Wreck of the Unbelievable are currently on show at the Galleria Borghese in Rome and the Fondation Cartier in Paris

Around the same time as the redundancies were announced, Hirst began to use the furlough scheme, topping up staff wages to 100%. During the first consultation meeting in May, staff questioned whether the scheme could be extended, even just on the government’s contribution. They were told, however, that maintaining current staffing numbers on furlough was still costing the company. Although Hirst’s representatives acknowledged that the furlough scheme was designed to support staff until it was safe to return to the studio—if there was work for them to do on their return, one representative also pointed out that most work had dried up.

According to one former member of staff who spoke to The Art Newspaper, after “weeks of bargaining”, an extension of the furlough scheme until October 2020 was agreed. Several ex-employees say they worked for Hirst for less than two years so were not entitled to a redundancy payout from Science (UK).

Over the past few months, former staff say jobs similar to theirs have been re-advertised on multiple recruitment sites. One listing, posted on Job Omega Resource Group in May, was for an art assistant in Stroud, Gloucestershire. Duties included fabricating and handling 2D and 3D works of art. The advertisement has since been removed.

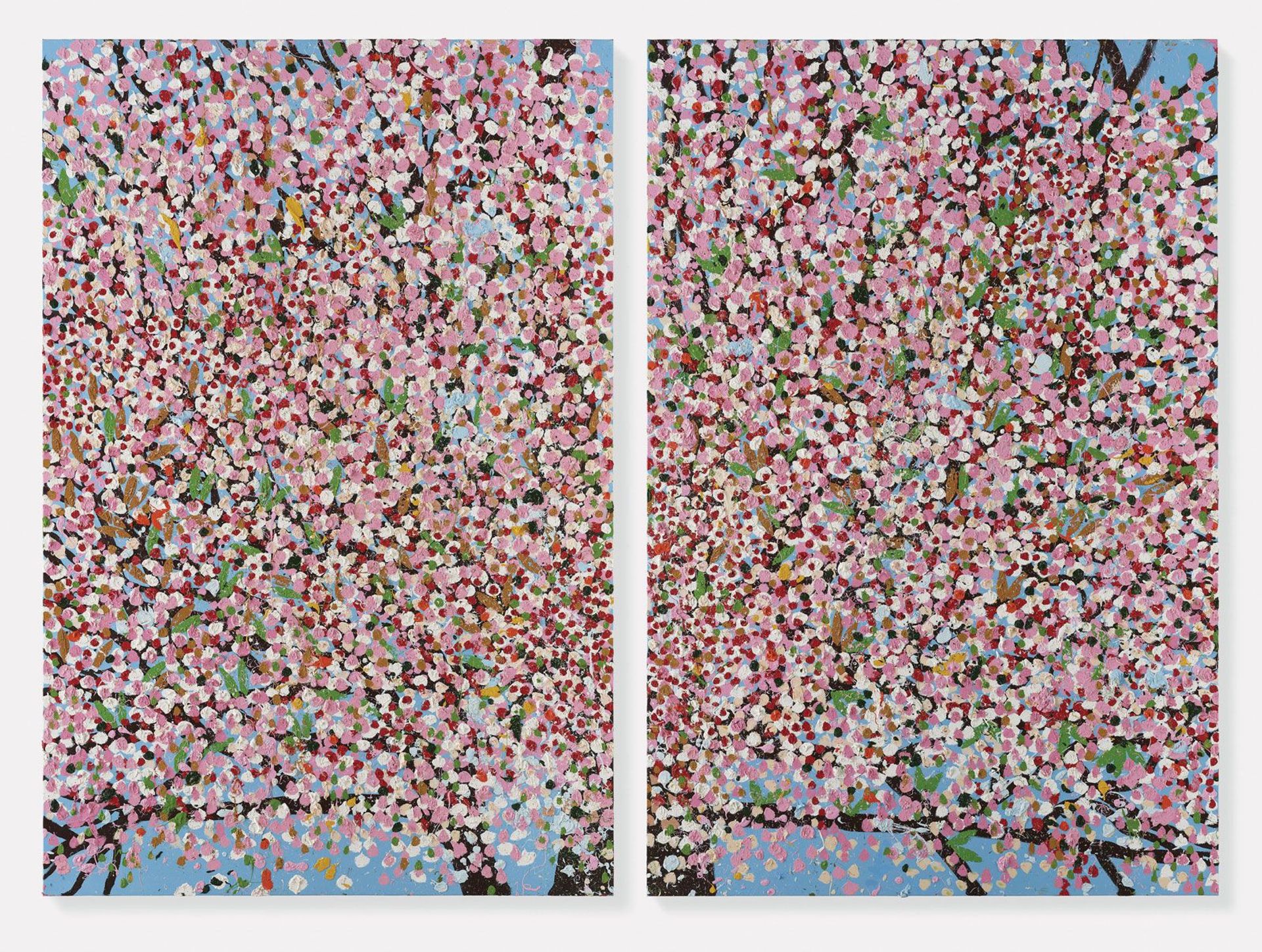

Hirst's Renewal Blossom (2018) is currently on show at the Fondation Cartier in Paris © Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates. Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2021

Hiring and dismissing staff as his business expands and contracts appears to be an ongoing strategy for Hirst. In 2018, the artist streamlined his business to “focus on his art”, laying off 50 employees, mainly working in finance and IT, although there were some losses in his London and Gloucester studios.

As one former employee who worked for Hirst for three years before being made redundant in October 2020 wrote on the recruitment website indeed.com: “During my three years there were multiple rounds of redundancies to remove staff. These positions were largely re-staffed within a matter of months. The business is effectively run by lawyers, and staff are treated as disposable. If job security, dignity and being appreciated at work are important to you, Science may not be a good fit.”

The 2018 redundancies heralded a shift from the large-scale sculptures Hirst spent ten years producing for his 2017 multi-venue Venice exhibition, Treasures of the Wreck of the Unbelievable, to a focus on painting. Some of the fruits of that labour are currently on show at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, where 37 out of 107 of his new Cherry Blossom paintings are on show until January 2022.

Banking on it

While the Paris show was a long time in the making, other exhibitions which opened this year appear to have been organised at short notice. They include Hirst’s year-long takeover of Gagosian Britannia Street and his exhibition in St Moritz, Switzerland, which opened in January and included works from key series including his large-scale installations of animals pickled in formaldehyde and sculptures from Treasures of the Wreck. Works from Venice are also on show at the Galleria Borghese in Rome until November.

Meanwhile, Hirst’s latest project, The Currency, marks another deviation in his art-making business towards editions and multiples and has been produced in collaboration with the publishing company, Heni. The project makes use of 10,000 oil paintings on paper created five years ago, with each work now linked to a corresponding NFT (non-fungible token). Buyers can purchase the NFTs for $2,000 each, but two months after acquiring the token must decide whether to keep it or trade it for the physical work. If the former, the drawing will be destroyed; if the latter, the NFT will be deleted from the blockchain.

Either way, Hirst stands to make $20m.