A claim by the heirs of Robert Graetz, a Jewish textiles entrepreneur who died in the Holocaust, for a painting by Lovis Corinth in the collection of Berlin’s Stadtmuseum has been rejected by Germany’s Advisory Commission for Nazi-looted art. The commission said there was too little evidence that Graetz lost the work due to persecution and that there was a risk that a previous owner might have a stronger claim.

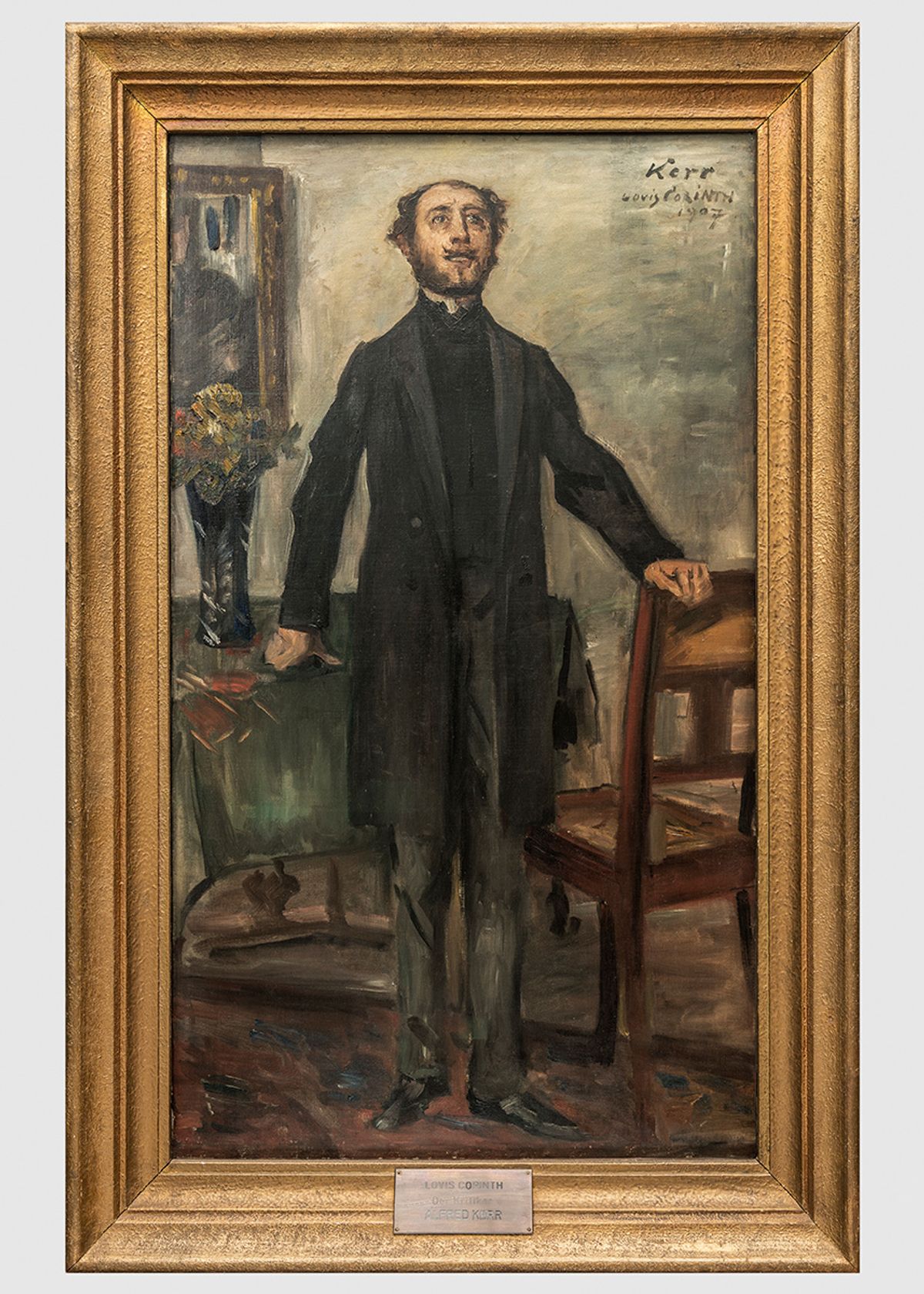

The 1907 portrait depicts Alfred Kerr, a prominent Jewish journalist and theatre critic and the father of Judith Kerr, the author of much-loved children’s books. The family escaped Nazi Germany in 1933. The portrait was part of Graetz’s extensive collection of Impressionist and Expressionist art, most of which, the Advisory Commission said, was lost as a result of persecution.

However, in the case of the Corinth portrait, the commission said there was no evidence that it was stolen or sold under duress—nor was it certain that Graetz was the primary victim of its loss. A previous owner of the painting also suffered persecution at the hands of the Nazis and Graetz’s heirs had received some compensation for the portrait in 1957, the panel said.

Graetz purchased the painting from Leo Nachtlicht, a Jewish architect who died in Berlin in 1942; his wife was deported and murdered. The commission said there was too little evidence that Nachtlicht sold it before 1933, the year the Nazis came to power. “We cannot rule out a sale after 30 January 1933 under circumstances that would today be deemed subject to restitution” to Nachtlicht’s heirs, the panel said.

Under the Nazis, Graetz was forced to liquidate his company and sell his Berlin villa to a company run by the SS. His children managed to escape, but Graetz was deported to a concentration camp in 1942 and died.

It is not clear how the Kerr portrait ended up in the possession of a woman named Gertrud Kahle, who survived incarceration in a concentration camp but killed herself shortly after the war ended. In 1942, Graetz had told the Berlin finance authorities that he was committed to paying Kahle a monthly sum—an indication, the Stadtmuseum argued, that they were close and the painting may have been a gift. In 1957, Kahle’s children reached a settlement with the Graetz heirs that allowed them to sell the painting. The Graetz heirs received 28.5% of the revenue.

The panel pointed out that the painting’s history is closely bound to the stories of three families persecuted by the Nazis—four, including Kerr, the subject of the portrait. “They were oppressed, robbed, deported, driven to flee or murdered,” the panel said. It recommended that the Berlin Stadtmuseum should honour the portrait’s history “in an appropriate way.”