Organisers at the Manchester International Festival (1-18 July) have defied the Covid-19 odds, launching a citywide smorgasbord of commissions across the visual and performing arts. The festival’s artistic director and chief executive, John McGrath, says that the pandemic prompted a reassessment, stressing that the programme "is very different to the one we had almost fully planned at the start of last year, but I hope it feels urgent and right". Here are three key art events from the eighth edition of the festival.

Marta Minujín's Big Ben Lying Down with Political Books, part of Manchester International Festival Photo: Fabio De Paola / PA Wire

Marta Minujín's Big Ben Lying Down with Political Books

Piccadilly Gardens (until 18 July)

The public art piece that has roused the curiosity of most Mancunians is the humongous Big Ben lying prostrate in Piccadilly Gardens. The vast installation, formed to look like London's famous clock, was created by the Argentine artist Marta Minujín who has incorporated 20,000 books in to the piece that, say the organisers, “have shaped British politics” (the publications selected are eclectic, ranging from footballer Marcus Rashford’s You Are A Champion to comedian David Baddiel’s Jews Don’t Count).

Minujín’s work is around half the size of the real Big Ben clock tower, which forms part of the Palace of Westminster, the home of the UK parliament. The work can be interpreted a number of ways: does it reflect the state of Britain, which is arguably in decline post-Brexit? Or the break-up of the UK, symbolised by the fall of the mother of all parliaments and its most famous landmark?

Ticketed tours allow visitors to look inside, giving a peek into how the structure was assembled (a mass of scaffolding reveals that this is a feat of engineering as well as an aesthetic endeavour). It is not the first time though that the artist has made sculptures using books: when the Argentinian military dictatorship came to an end in 1983 she created The Parthenon of Books, a replica of the ancient Greek temple made from once-banned books. The work was recreated in 2017 on the site of Nazi-book burnings for Documenta 14 (2017) in Kassel.

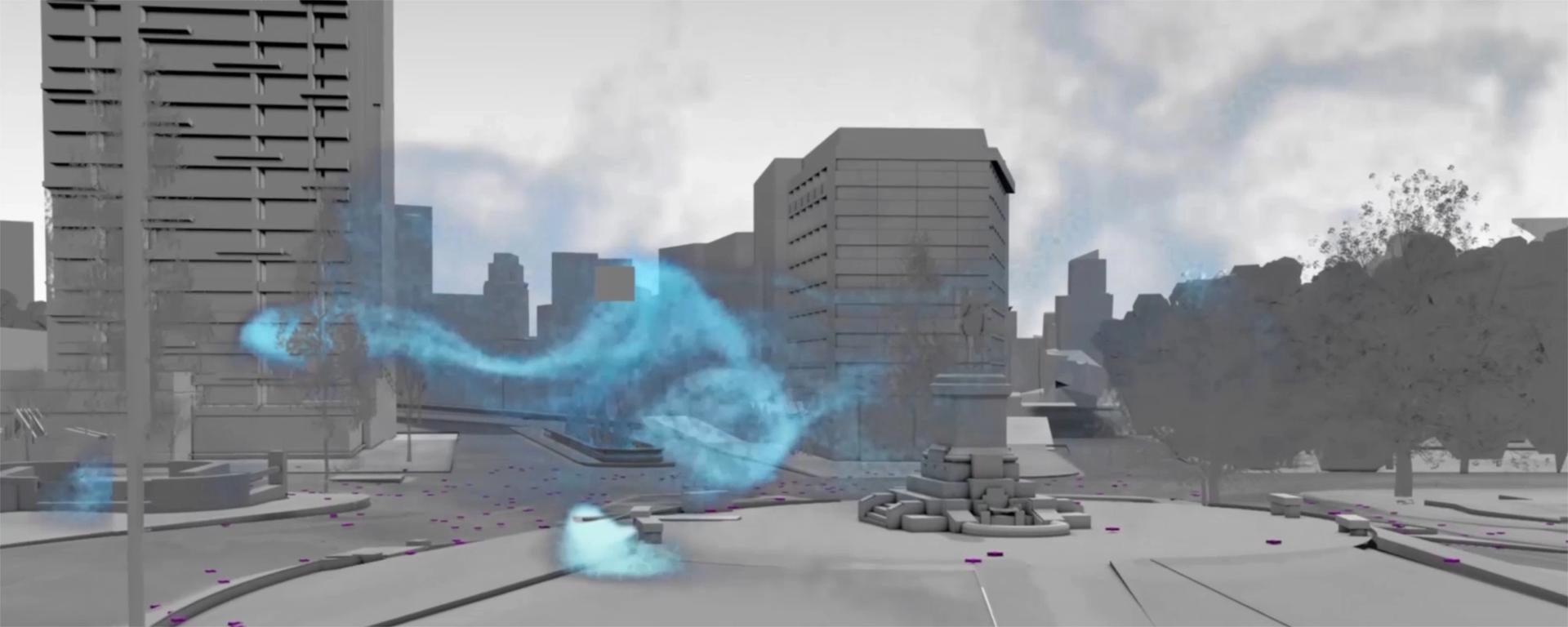

Forensic Architecture's Tear Gas in Plaza de la Dignidad (2019) Courtesy of Forensic Architecture

Forensic Architecture's Cloud Studies

Whitworth Art Gallery (until 17 October)

The London-based art and research agency Forensic Architecture, which was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2018 and included in the 2019 Whitney Biennial, has turned its penetrating gaze on companies and individuals polluting the atmosphere. This investigation is based on a relevant and frightening thesis: “Mobilised by state and corporate powers, toxic clouds colonise the air we breathe across different scales and durations.”

Traces of tear gas, airborne chemicals used in warfare such as white phosphorus, and petrochemical emissions are all tracked, the consequences of their use dissected and discussed. Case studies presented in this sleek, unsettling exhibition include an overview of the Safariland Group, one of the world’s major manufacturers of tear gas which is owned by Warren B. Kanders, the former vice chairman of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Forensic Architecture also analyse the use of white phosphorus which, a wall text says, “can cause severe injuries, burning directly through skin and bone” during conflict. The group examined videos from the 2008-09 Gaza conflict, when the chemical was used during Israeli attacks on Palestinian territories. Israel claims it used the corrosive material “as a ‘smoke screen’ and ‘in compliance with international law’’, the group says. Another film explores how 200 industrial plants located along an 85-mile stretch of the Mississippi River in Louisiana are contaminating local communities.

Laure Prouvost's The long waited, weighted, gathering Photo: Michael Pollard

Laure Prouvost's The long waited, weighted, gathering

Manchester Jewish Museum (until 18 July)

There is a big build up to Turner prize-winner Laure Prouvost’s new installation at the relaunched Manchester Jewish Museum. Visitors are encouraged to first digest the history of Jewish settlement in Manchester in the new permanent gallery, part of a two-year refurbishment costing £6m. Among the 30,000 items housed at the new institution is a letter from Helen Taichner whose family were murdered in the Holocaust. After she got a permit to travel from Katowice in southern Poland to Manchester, she wrote to a relative in 1946: “My happiness is boundless.” The permanent collection puts Prouvost’s piece in context, providing a backdrop to the artist’s composition. Visitors are ushered into the upper Ladies Gallery, where women gathered to watch the men worshipping below in the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue built by Sephardic Jews in 1894.

A screen unfolds to reveal an embroidered border created by the Jewish women’s textile group. Prouvost’s film then presents a series of characters—a mix of real and fantasy—that have anchored the Jewish diaspora in the city, from Sarah the formidable auntie to Esther who founded a dairy farm. The playful piece is typical of Prouvost, whose bizarre touches in the historical story include replacing the women’s faces with pigeon’s heads.