The curators of Documenta 14, which previewed to the press and invited guests on 7 June, have already proved that they are not afraid of taking risks. For the first time in the German quinquennial's 55-year history, half of the exhibition was unveiled first in Athens in April (until 16 July), and the other only now in its home city of Kassel (10 June-17 September). At a packed press conference, Adam Szymczyk, Documenta 14's artistic director, acknowledged that he had faced “political and financial issues” by staging the show in two locations.

In Kassel, as in Athens, the exhibition’s aim is to provide marginalised artists with an unprecedented platform while challenging dominant political, economic and cultural systems. "I accept that money has a lot of power but not the full power to determine the course of our actions," Szymczyk said in his short speech to the press. "We can ask if in the structures of power there is a space for us to negotiate; our sort of power versus their sort of power. The outcome is in our hands and to some extent in your hands too.”

Most of the 160 or so living artists in the show have works in both Kassel and Athens. The exhibition, titled Learning from Athens, has grown from its usual 100-day run to 163 days. It also features an extensive radio and television programme, as well as publications and public events. To help him organise this enormous bi-location undertaking, Szymczyk has enlisted the help of almost 20 curators and advisers. With a budget of €37.5m, half of which comes from German taxpayers, it is one of the best-funded visual arts festivals in the world.

The Kassel leg of the show is staged across 33 sites in the industrial German city. The main venues include the traditional heart of Documenta, the Fridericianum, as well as the Documenta Halle and the Neue Galerie, plus its latest additions, the “Neue Neue Galerie” (the city’s former main post office) and the Grimmwelt, a new museum opened in September 2015 dedicated to the 19th-century fairy-tale-writing brothers who lived in Kassel. Other sites being used for the first time are the Hessisches Landesmuseum, the Stadtmuseum Kassel and a number of places in the largely-immigrant neighbourhood of Nordstadt. Among the more offbeat venues this year are a disused U-Bahn station and one-time retail spaces known as the “glass pavilions”. Certain to become one of the most recognisable works of this edition is the Argentinian Pop artist Marta Minujin’s Parthenon of Books towering over the Friedrichsplatz opposite the Fridericianum (see below).

Reactions to the Athens show have so far been muted with many awaiting the Kassel iteration to open; and with so much to see, this huge exhibition is sure to take some time to digest. Whether it manages to change unconvinced hearts and minds remains to be seen. Here is a look at some highlights from four of the main sites on the preview day.

Fridericianum: Gifted to the Greeks

Since Documenta’s first edition in 1955 the Fridericianum museum—built in 1779—has been the exhibition’s central venue. It is symbolic that it has been turned over to a Greek curator, Katerina Koskina. She is the director of Greece’s National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens (known as EMST), which was in turn the core of Documenta 14’s presentation in Greece. It presents works from the collection and loans: a mix of big international names, and lesser-known Greek artists since the 1960s who for many will be a highlight of the exhibition. It shows how Greek artists have been addressing many of the same issues as the rest of Documenta 14 over the past 50 years, as well as their relationship to major art movements such as Arte Povera.

Königsplatz and Friedrichsplatz: New monuments

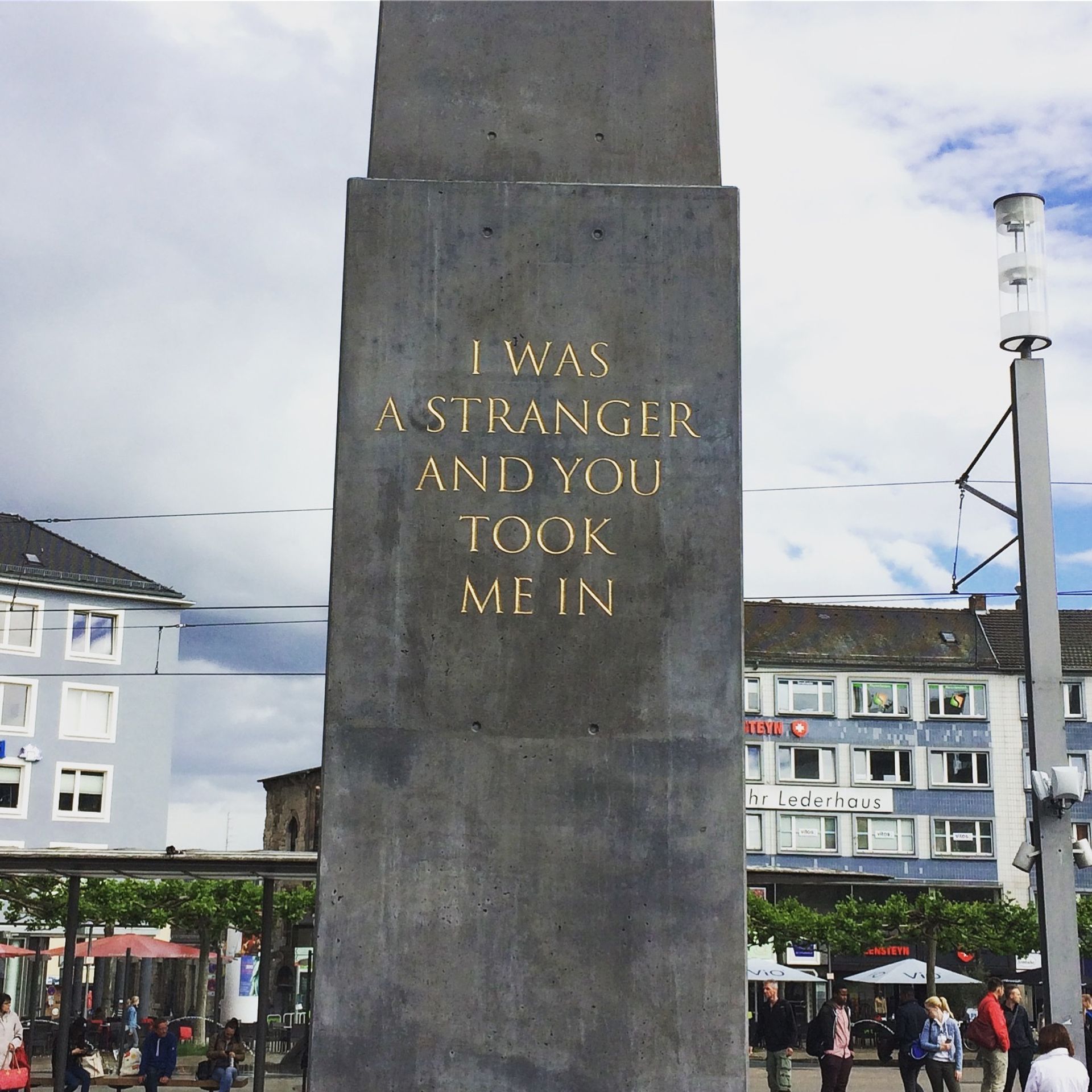

Monuments, memory and calls to political action are recurrent themes of this year’s Documenta. While there are major public sculptures dotted around Kassel for the duration of the show, two have been placed in juxtaposition to each other. In the Königsplatz, Olu Oguibe has built a concrete obelisk, Monument for Strangers and Refugees (2017). On its side, it has a famous line from the New Testament Book of Matthew, “I was a stranger and you took me in”, in English, German, Turkish and Arabic. Obelisks are generally associated with ancient Egypt and Africa, and were much-prized by invaders from the Romans to Mussolini who frequently removed them and took them home (the famous Obelisk of Axum was finally repatriated from Italy to Ethiopia in 2005). In the nearby Friedrichsplatz, another work draws on the architecture of antiquity, the Argentinian artist Marta Minujin’s 1:1 scale recreation of the Parthenon made from once-banned books. It stands as a reminder of the enthusiasm of governments of many political stripes for censoring words and ideas.

Neue Galerie: Ghosts of the Gurlitts

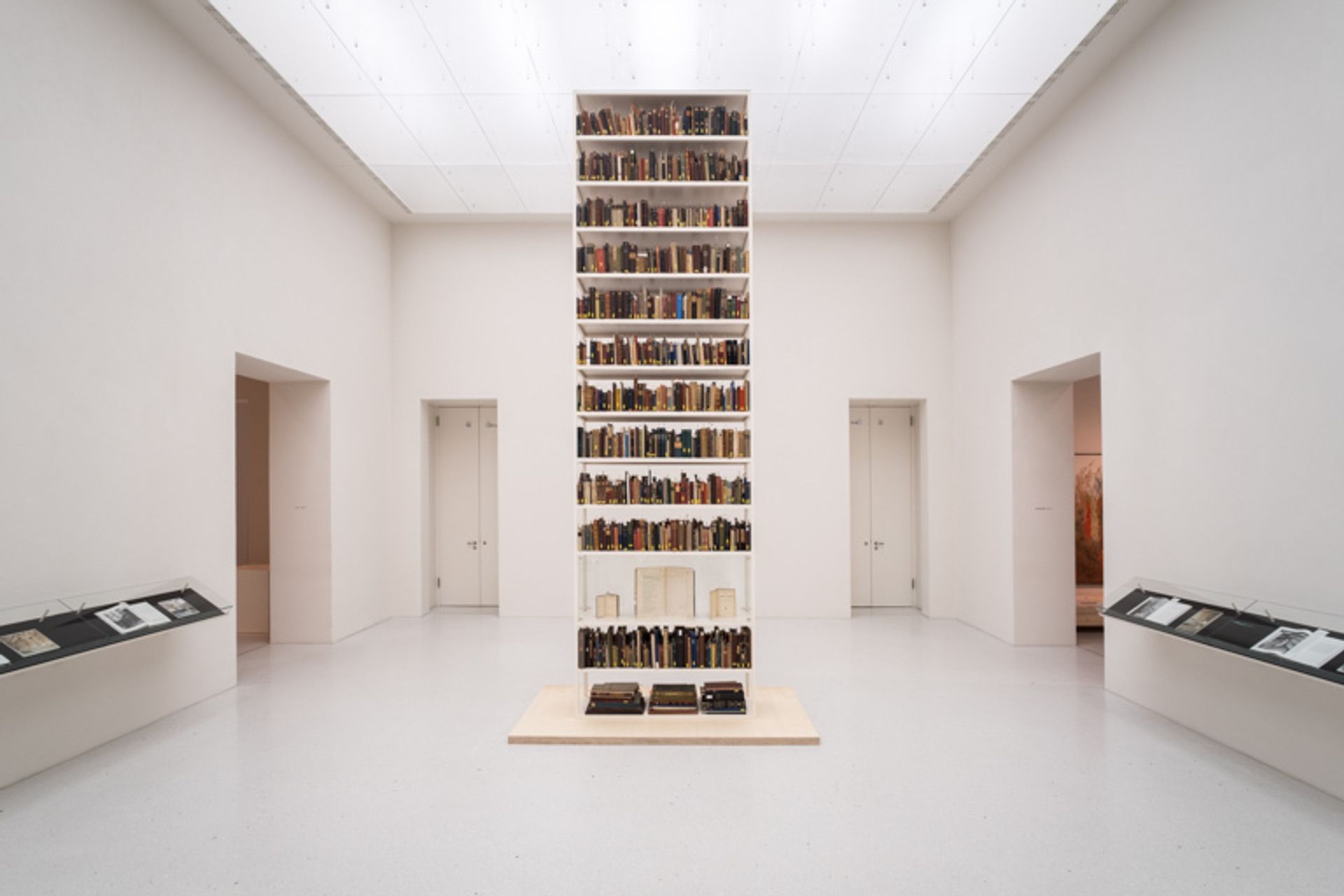

The Neue Galerie is where Adam Szymczyk wanted to show the Gurlitt hoard, that now infamous cache of 1,500 works that was found stashed away in a Munich apartment in 2012. For whatever reason it proved impossible to organise but the ghost of its discovery still pervades this venue. Central to the display is Maria Eichhorn’s Rose Valland Institute. Named after the French art historian who saved countless works of art from the Nazis, Eichhorn’s project calls on the public to help solve restitution cases, a responsibility that has long been the remit of institutions and governments. Works by Cornelius Gurlitt’s aunt, Cornelia Gurlitt, an artist who committed suicide after the First World War, are also on show.

Neue Neue Galerie: Into new neighbourhoods

Described as “Kassel’s Turbine Hall”, by the Documenta 14 co-curator Dieter Roelstraete, this former post office is one of the main venues in Nordstadt, a neighbourhood largely inhabited by immigrant communities. Former loading bays on the ground floor act as impromptu galleries where artists including Joar Nango, Maret Anne Sara and Daniel Garcia Andujar are given mini solo shows, while a film by Theo Eshetu, projected onto giant reproductions of German exhibition posters of ethnographic art, dominates the space. Activism is a thread that runs through the presentation, chief among which is the harrowing account by the Society of Friends of Halit of the problematic murder inquiry of the young Turkish man, Halit Yozgat, who was gunned down by neo-Nazis in Kassel in 2006.