• Read our interview with architect Frank Gehry here as well as other must-see art and culture spots in Arles

One day in late November 2019 marked an important milestone at the Parc des Ateliers, the 27-acre creative campus that has been under development in the southern French city of Arles since 2008. “Anyone who plants trees believes in the future,” said the landscape architect Bas Smets, as he firmly placed a young and healthy umbrella pine in its designated spot. The first of many, it began a transformative process of landscaping that will create its own, kinder microclimate in this hot and salty part of France. “We’re planting 180 now, and 400 in the next year,” Smets said. “Not just pines, but Holm oaks, pistachios, purple myrtles… And laying 6,000 metres of grass.”

The Parc des Ateliers is the home of LUMA Arles, a major initiative directed by the Swiss pharmaceutical heir and art patron Maja Hoffmann, which aims to collapse the boundaries between art, culture, human rights and environmental issues. It is a place where art will be made and shown, where the biodiversity of the region will be explored and harnessed, where conferences ranging across all kinds of cultural investigations will take place and educational opportunities expanded, and where locals and international visitors will find themselves wandering in the shady canopies of trees, around a spectacular man-made lake (fed with the unused water that runs to the river Rhône from the Alps), or having a locally sourced meal in one of two restaurants.

The centrepiece of the 27-acre LUMA campus is Frank Gehry’s 56m-tall tower. Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889; inset) was one of the inspirations for Gehry’s design Photo: © Rémi Bénali

“It is not about hanging a collection,” Hoffmann tells The Art Newspaper, “but social impact and activating the region”. The entire site is due to open officially on 26 June, having been delayed a year by the Covid-19 pandemic. Its founder is undeterred by the wait. “It has meant that we have finished the garden, and we had so much more time to invite artists to take part in longer residencies,” she says.

Hoffmann established the LUMA Foundation, named after her children Lucas and Marina, in Zurich in 2004. It has since supported creative projects all over the world, from the Park Avenue Armory in New York to the Tanks of Tate Modern and the Serpentine Galleries in London. Although Hoffmann comes from three generations of art collectors, her interest is in processes and possibilities as much as outcomes. “It is the artist, and the artistic discourse, that I’ve always wanted to nurture and protect,” she says. “And now, as the world is beginning to break down, I say the voice of the cultural producer, the creative person, is more crucial than ever—to deliver interdisciplinary cultural solutions.”

Looking to the future

The Parc des Ateliers is a poignant place from which to take on the future. Sitting just outside Arles’s Roman city walls, it was once an industrial site for the national railway company SNCF, producing and repairing locomotives in its huge sheds and making a hefty contribution to the local economy, until it closed in the mid 1980s. Now those buildings have been renovated by the architect Annabelle Selldorf and repurposed for LUMA’s rather more post-industrial pursuits. She has given them new clay tile roofs and restored their handsome 19th-century steel columns and trusses.

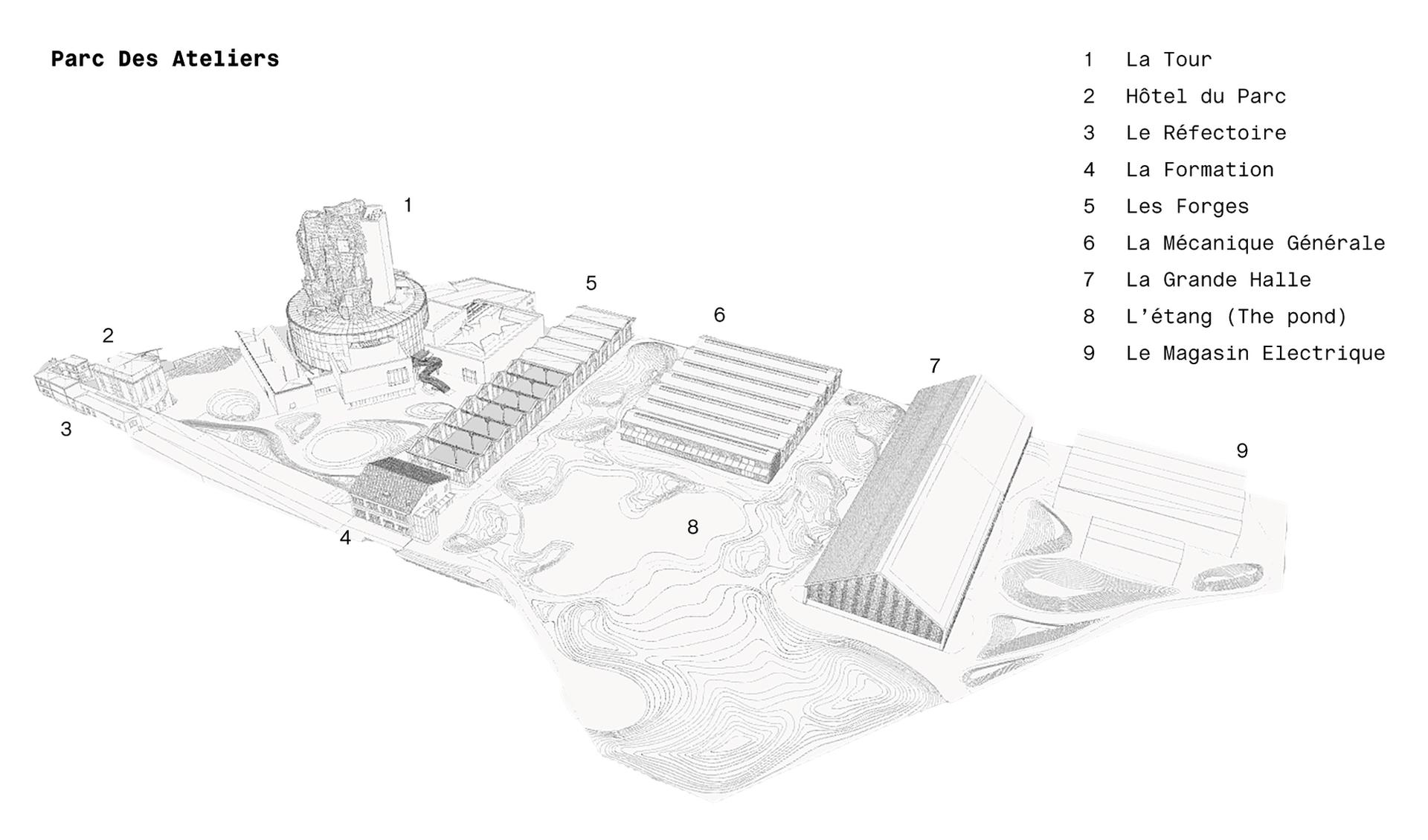

A map of the LUMA Arles site Courtesy of LUMA Arles

With a population of 54,000, Arles has a high unemployment rate—12% compared to the national average of 9%—and it is hoped that LUMA will help to dent that (it is already employing around 150 people), as well as stretching out the city’s currently seasonal, primarily touristic, appeal over the whole year. There is plenty to see here, from the Roman amphitheatre to the Vincent van Gogh foundation, of which Hoffmann is president. A project initiated by her father Luc, that foundation opened in 2014 to honour the artist who, more than anyone, put Arles on the map, although he only spent one tortured but productive year here from 1888 to 1889.

That the buildings of the Parc des Ateliers and its desertified terrain—a concrete base covered in dusty gravel—needed considerable repair was beyond dispute. But the introduction of a new building on the site, designed by the superstar architect Frank Gehry, has been a rockier ride. Hoffmann met him in 2005, when she co-produced a documentary called Sketches of Frank Gehry, and appointed him to design a landmark structure for the LUMA campus without a competition. “Frank is an artist,” she says. “And I fell in love with his imagination, which has no bounds. His spirit is great. His talent is enormous.”

Maja Hoffmann, the artistic and architectural programme for LUMA Arles Photo: Inez & Vinoodh; courtesy of LUMA Arles

Gehry’s initial scheme for two metallic towers met with considerable opposition. The architect described them as “evoking the local, from Van Gogh’s Starry Night to the soaring rock clusters you find in the region”, but in 2011 the plans were rejected by France’s National Commission of Historical Monuments, on the grounds that the buildings would obscure views of the Alyscamps, the Roman necropolis.

In 2013, a second design in a different position on the north of the site—a single twisting tower with 13 levels and 11,000 reflective stainless-steel plates—was approved. At the stone-laying ceremony in 2014, Hervé Schiavetti, the city’s new Communist mayor, made a rousing speech, exclaiming: “Vive la gloire arlésienne! Vive Frank Gehry! Vive Maja Hoffmann!” Now the structure is complete, its upper floors are the only place in Arles to see the astonishing landscape beyond the city.

Although Hoffmann is Swiss by nationality and has homes around the world, her heart is in the Camargue region south of Arles. “My parents had already laid down roots before I was born, and we moved here when I was one week old,” she has said. “It’s where I grew up. The big skies are something I think about wherever I am.”

Gilbert & George's The Great Exhibition (1971-2016), which was on show in Luma Arles's Mécanique Générale in 2018/19 Photo: Lionel Roux; courtesy of Luma Arles

Luc Hoffmann, an ornithologist, established the ground-breaking Tour du Valat research centre for wetlands conservation in the Camargue in 1954, before co-founding the World Wildlife Fund in 1961. “He was a pioneer,” his daughter says. “People thought he was a dreamer, but it was important what he did, and when he did it.” Now Maja, who was born in 1956, is following in his philanthropic footsteps, adding art into the mix.

Curatorial collaborations

In 2009, Hoffmann assembled a core team—the curators Hans Ulrich Obrist, Tom Eccles and Beatrix Ruf, and the artists Liam Gillick and Philippe Parreno—to begin conversations around art and its production. “We saw it as a huge opportunity to think of new exhibition formats, with artists’ voices at the very centre,” says Eccles, the executive director of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, and a curator at the Park Avenue Armory in New York. “We see Arles as an incubator, a place to test audiences and ideas.”

Indeed, the group’s first exhibition at LUMA Arles, Solaris Chronicles in 2014, tested audience credulity, as invigilators choreographed by Tino Sehgal moved models of Gehry buildings through the cavernous shed called La Mécanique Générale. The core team has since been extended with younger voices: the US artist Ian Cheng, the Qatari-American writer and film-maker Sophia Al-Maria and the Spanish philosopher and curator Paul B. Preciado.

The original core group behind Luma Arles: (from left) Liam Gillick, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Maja Hoffmann, Beatrix Ruf, Philippe Parreno and Tom Eccles Photo: Jonas Unger; courtesy of Luma Arles

In July 2018, the senior curator Vassilis Oikonomopoulos arrived too. Previously at Tate Modern, he had worked on Philippe Parreno’s ambitious Turbine Hall installation in 2016. “Arles is a unique opportunity,” he says, “and more entwined with nature than most cities. At LUMA we’re not locked into a conventional schedule of having to put on a new show every three months. We can be flexible and take risks.” Hoffmann is the boss, but everyone has their say. Now, as the very definition of a museum is changing, and traditional binary divisions—between genders or between art and nature—are dissolving, nowhere is better situated to respond than this freewheeling set-up.

“We saw it as a huge opportunity to think of new exhibition formats, with artists’ voices at the very centre”Tom Eccles, part of LUMA Arles's core team

Oikonomopoulos is overseeing a number of exhibitions for the grand opening, including one by Pierre Huyghe in the Grande Halle that will be partly constructed by ants and bees, and another with new works by P. Staff and Jakob Kudsk Steensen in La Mécanique Générale. Steensen started a six-month residency in Arles in January 2020 and ended up staying until September, researching the Camargue wetlands and forensically filming the life cycles of animals and plants, their natural birth, interdependency and decay. Seen through virtual reality, his representation of the region’s complexity has stunned even knowledgeable locals, including Hoffmann herself.

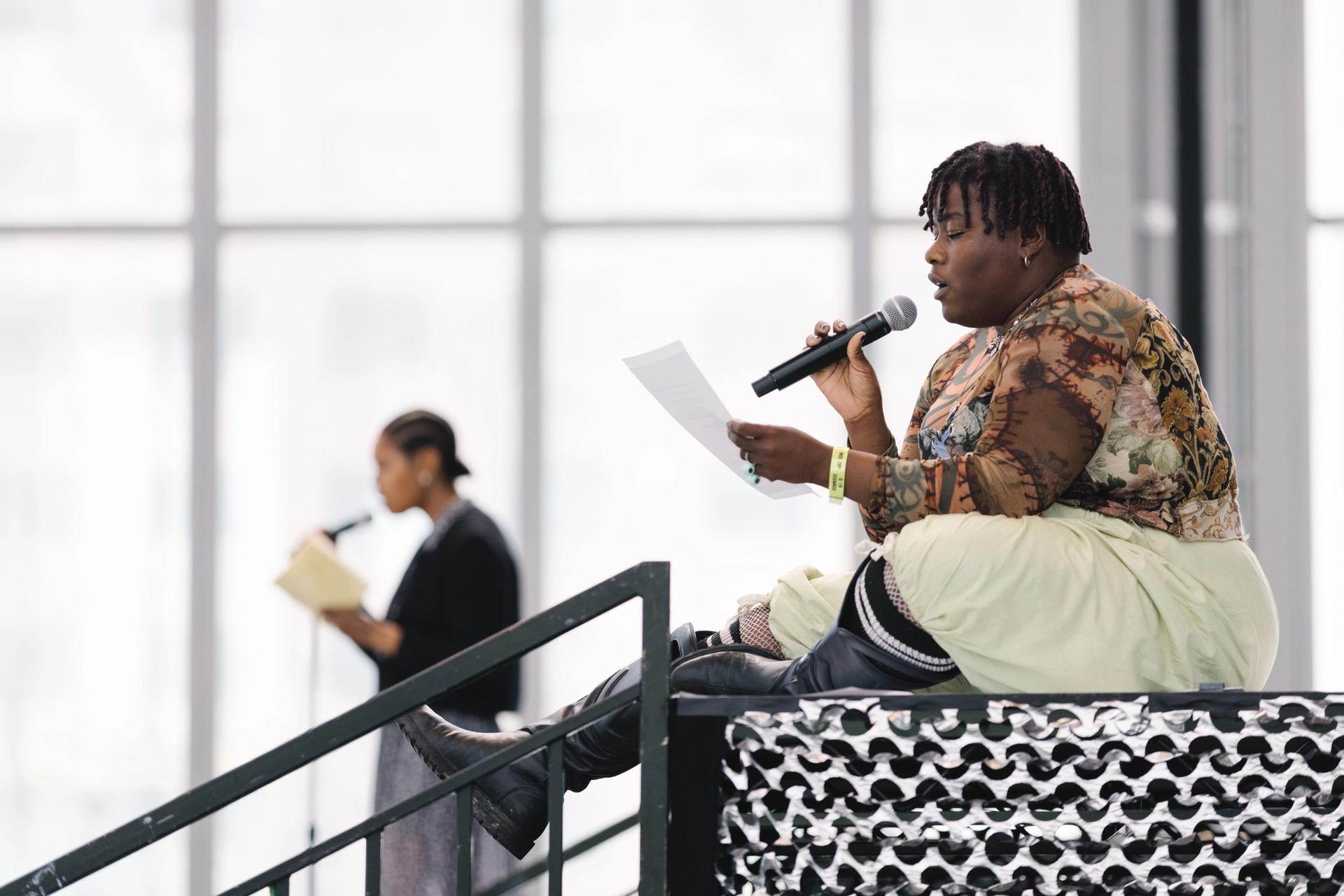

Attendees at Luma Days—an annual forum of art and ideas—in 2018 at Grande Halle at Parc des Ateliers, Luma Arles Photo: Adrian Deweerdt; courtesy of Luma Arles

Art from Hoffmann’s personal collection and that of the LUMA Foundation will be dotted through the Gehry tower: John Akomfrah’s three-channel video Four Nocturnes (2019) on the underground level, a glow-in-the-dark skate park by Koo Jeong A on the terrace and slides by Carsten Höller on level two. There will also be a presentation from the collection of Hoffmann’s grandfather Emanuel, which is permanently housed at the Schaulager in Basel. “We realised, talking to artists from Rachel Rose to Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, that it was works from this collection, by [Joseph] Beuys perhaps, or Bruce Nauman, that had inspired them to become artists. So we decided to show some—it’s like the genetic material for artists and curators,” Oikonomopoulos says.

Elsewhere in the building are the fruits of Atelier LUMA, an experimental workshop established by the design curator and thinker Jan Boelen in 2016. Currently based in La Mécanique Générale, the Atelier will move next year into a new building designed by the Turner-prize winning collective Assemble. “Maja approached me to design a chair,” Boelen recalls, “but I wanted to go right back to the soil of the region.” He has since invited a series of designers to Arles to develop new materials from local resources, and new methods of interrogation. The chair never happened, but the results of their research will be visible throughout the Gehry building: mosaic tiles created from readily available algae are in the bathrooms, while the corridors are lined in panels made from salt mined nearby. (“It’s anti-bacterial—we’re thinking of door knobs next,” Boelen says). In the restaurant, the Italian designer Martino Gamper has used a bioplastic based on discarded olive pits for parts of the chairs, and invented upholsteries of rice straw and local wool.

“It’s a bit like a dream,” Boelen says. “A place to continually push ideas, and create systems that might be applied anywhere one day.” LUMA Arles, it seems, is really just a beginning. Or as Hoffmann says: “From here, its ideas will go out into the world.”

Programming highlights

Precious Okoyomon’s terrarium

Tower, Main Gallery

In May, the Nigerian-American poet, chef and artist won the Frieze Artist Award in New York, a commission supported by the LUMA Foundation. Okoyomon also undertook a residency in Arles from September to December last year. “It made me write new poems,” they say. “The mistral wind makes you feel like God is there.” They have created a new work that is “a sort of terrarium, filled with snails and kudzu—which are both invasive species”. A box on wheels that can be moved from indoors to out, the work deals with ideas of undesirability and demands that these unloved animals and plants be cared for in various ways.

Precious Okoyomon's This God Is a Slow Recovery at Frieze New York 2021 as part of the Frieze Artist Award supported by the LUMA Foundation Photo: Da Ping Luo; courtesy of Da Ping Luo/Frieze.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s Endrodome (2019)

Tower, Level 2

A little like attending a séance, five viewers at a time are invited to sit around a table and take in Gonzalez-Foerster’s first work in virtual reality. The eight-minute experience, which was presented at the 2019 Venice Biennale, immerses viewers in an hypnotic monochrome environment, before moving to dazzling, disconcerting fields of colour. Gonzalez-Foerster was inspired by the experience of sound-induced trance states she achieved with the musician and shaman Corine Sombrun, who also created the soundtrack for this piece.

Philippe Parreno’s meta-film

Permanent Gallery

Parreno has used the Covid-19 lockdown period to explore unused footage from a number of existing film works. “It was like opening a Pandora’s box of outtakes,” he says. Material from Ann Lee (2011), Marilyn (2012), sequences from his filming of a cuttlefish and its alien perspective, and more will come together in a meta-film, to be screened in a 350 sq. m gallery with a strong and disruptive acoustic reverb. Parreno describes the room itself as “a sentient being” that will also receive outside data from the wind, temperature and sunlight. This site-specific piece will only ever be seen at LUMA Arles.

• Read our interview with architect Frank Gehry here as well as other must-see art and culture spots in Arles