In the year since the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, US art museums have faced greater pressure than ever before to root out racial injustice in their institutions, from a lack of diversity in their workforces and audiences to a longstanding canonical emphasis on white Western artists.

Floyd’s death on 25 May 2020 and the ensuing anti-racist protests across the country led many museums to issue declarations that “Black Lives Matter”—inviting derision from those who found the words hollow. In the months that followed, numerous art institutions drew up detailed plans to advance diversity and inclusion across their operations.

The Art Newspaper asked 22 American museums about the progress they have made in diversifying their staffs, exhibition programmes, permanent collections and audiences over the past year. Nine did not reply to requests for information.

Only one respondent provided a comprehensive budget estimate for its diversity and inclusion initiatives: the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), with $3m. (However, the National Gallery of Art (NGA) said that it had secured a dedicated endowment gift of $8m for such efforts.) Several museums said that no cohesive figure was available for work that is spread over different departments, from human resources to curatorial to education.

Still, the survey responses were telling. Most visibly, exhibitions and acquisitions of under-represented artists are multiplying as curators seek to revise enduring white- and male-dominated art historical narratives. Yet outreach to new audiences is faltering, amid health restrictions that limit visitor numbers overall and preclude the group trips that had been a source of sustenance for underprivileged schools.

Diversity and inclusion directors are now on staff at leading art museums in New York, Washington, DC, Boston, Seattle, San Francisco, St Louis and Toledo. And in a possible bellwether for other institutions, the Phillips Collection enlisted the Washington philanthropists Lynne and Joe Horning in February to permanently endow its diversity position, created in 2018, with a $2m gift. Other museums are hiring consultants to lead anti-racism staff training and draft workplace discrimination policies that empower employees.

And even as museums reel from revenue losses due to Covid-19 closures and limited visitor capacity, they are making cautious progress in appointing people of colour to senior posts. After a period of hiring freezes, layoffs and furloughs, reopenings have raised the possibility of recruitment, with a greater emphasis on diversity.

Meanwhile, coalitions of museum employees have spoken out, vigorously challenging entrenched practices among senior leadership.

Lial Jones, the president of the board of the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) and the director and chief executive of the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California, finds it notable that museum professionals are rallying against the status quo. “I think a lot of the pressure is from within and not without,” she says. “Staffs have brought these issues to the fore and created greater awareness.”

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York received a scathing letter from members of its curatorial department in June 2020 denouncing an “inequitable work environment that enables racism, white supremacy and other discriminatory practices” and demanding reforms. In August, the Guggenheim unveiled a 13-page action plan pledging to hire a senior manager to implement a host of goals over two years and drive an anti-racism conversation within the museum.

Since then, the museum says it has prioritised diversity and inclusion on the agenda of every meeting and launched a paid internship programme. All staff members have completed anti-racism training, the institution says.

Richard Armstrong, the director of the museum and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, says he is in contact with the curatorial staff “nearly on a daily basis” and that the group provides critical observations on the museum’s culture. Of the charges of systemic racism, he says: “I’ve come to terms with it in society at large. To the degree that we reflect prevailing values, I would say, it’s probably applicable.”

Richard Armstrong, the director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and its associated foundation Photo: David Heald; © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Much is riding on the appointment of Naomi Beckwith, who takes over as deputy director and senior curator in June. Beckwith, a senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, has masterminded shows delving into racial identity and recently helped plan the New Museum’s groundbreaking exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, an exploration of Black loss in response to racist violence. “I think she will be a very persuasive leader among the curators and out in the wide body of the institution,” Armstrong says. “She’s got a range of acquaintanceship with artists, some of whom we’re not familiar with, so to the degree that she’s incorporating new people into the dialogue and underscoring the values of others, we’ll gain from that.”

Naomi Beckwith, the incoming deputy director and senior curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Beckwith succeeds Nancy Spector, who resigned last October after an extended controversy over allegations of racist mistreatment levelled by a Black guest curator, Chaédria LaBouvier, who organised a 2019 show of works by Jean-Michel Basquiat. An independent inquiry commissioned by the museum found that there was no evidence that LaBouvier was mistreated because of her race.

As of May, the Guggenheim’s 259-member staff is 70% white, according to the museum. Eight of the 21-member curatorial staff, or 38%, identify as Black, Indigenous or people of colour (Bipoc), up from 26% a year ago. After a hiring freeze and salary cuts in 2020, the museum is beginning to fill open positions selectively: Armstrong says he anticipates “a few other additions” to the curatorial ranks, with “an open mind” and “an open call”.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, meanwhile, came under fire weeks after Floyd’s death when 15 employees signed a letter urging its leadership to acknowledge “a deeply rooted logic of white supremacy and culture of systemic racism at our institution”. The museum was also targeted in a letter signed by around 900 people from New York cultural institutions expressing “outrage and discontent” over mistreatment of people of colour in their ranks.

The Met responded last July with a 13-point anti-racism and diversity plan that committed the museum to recruiting Bipoc candidates across departments. It says it has since appointed people of colour to several leadership positions, including the head of the design department, the chair of the education department, the head of government affairs and curatorial roles. The Met did not provide statistics for the current racial composition of its staff, however.

Its recently hired chief diversity officer, Lavita McMath Turner, says the museum’s senior staff members have taken part in anti-racism workshops that she hopes will lead to “a transformation and culture change”. Training for board trustees is planned this autumn, she adds.

Lavita McMath Turner, the chief diversity officer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

“We’ve done an enormous amount in the last year because we believe the Met is a brilliant institution that has fallen short on these issues of race, equity and justice,” says Daniel Weiss, the Met’s president and chief executive. Among other steps, the museum began a fully paid internship programme this spring, supported by a $5m gift from the donor Adrienne Arsht, that encourages the participation of students from more diverse backgrounds. The Met also plans to issue a full accounting of its history through the prism of race and exclusion.

Other major US museums have also been charged with falling short amid a litany of racial controversies. The Whitney Museum of American Art cancelled a show after Black artists discovered that it had acquired their work without their knowledge through discounted sales intended to benefit racial justice causes. (The Whitney estimates that 41% of its 361 employees identify as people of colour. Of its 14 curators, four, or 29%, are people of colour, the museum adds.)

The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) commissioned an outside inquiry after employees complained of dictatorial behaviour and an insensitivity to gender and race by its director, Salvador Salort-Pons. He was allowed to keep his position subject to increased board supervision, an outcome that prompted multiple trustees to resign. The museum says it has embarked on an inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility project funded by a 2019 grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Sciences and that a hotline has been set up for whistleblower complaints. Of its 365 employees, it says that 177 or 48% are people of colour, and that three, or 23%, of its 13 curators are people of colour.

The Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields apologised in February for a job posting for a director who would maintain its “traditional, core, white art audience” as well as striving for more diversity. A torrent of criticism led Charles Venable, the president of Newfields, to resign. “We pledge to do better,” said the institution's board of governors.

The tempest was a form of vindication for Kelli Morgan, the museum’s former associate curator of American art, who resigned last July, citing a “toxic” work environment that failed people of colour like herself. The job posting “upset the field and the public”, she says, but it was “only the tip of the iceberg”.

Kelli Morgan, the former associate curator of American art at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields Courtesy of Kelli Morgan

For Morgan, the crowning blow of her tenure was what she described as a “racist rant” at an acquisitions meeting with members of the museum’s all-white board, prompted by a proposal to acquire a vase by Roberto Lugo that depicted the former quarterback and activist Colin Kaepernick and the abolitionist John Brown. She says “a wealthy white donor” objected to Kaepernick’s kneeling to protest racial injustice during the national anthem before football games. “I said no, that was not OK. My reaction was seen as unprofessional.” Morgan had been hired to promote diversity in the museum's collections and displays. (The museum did acquire the vase.)

Black trustees unite

In an American museum culture fuelled by private philanthropy, some critics say that wealthy, predominantly white trustees and donors can stand in the way of diversity efforts. A 2017 survey by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) encompassing around 850 institutions found that almost half of US museum boards (46%) were totally white. That year, the AAM launched Facing Change, an initiative supporting board diversity at 51 museums in Chicago, the San Francisco Bay Area, Texas, Jackson, Mississippi and Minneapolis-St. Paul. It is backed by $4m in grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Alice L. Walton Foundation and the Ford Foundation.

And last September, the Black Trustee Alliance for Art Museums was formed to champion Black staff members, support Black trustees, flesh out sparse Black narratives in museum displays and programmes, and encourage museums to support more minority-owned business partners.

The makeup of boards at “several significant institutions” is already evolving, says Pamela J. Joyner, a prominent collector on the alliance’s steering committee who sits on the boards of the J. Paul Getty Trust, the Art Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “This suggests that a new profile of trustee is not only present, but that these individuals have meaningful agency.”

On the Guggenheim board, the Black artist Rashid Johnson, known for probing meditations on race and class, has been a key advocate of the need for institutional change, according to Armstrong. The museum says two of its 26 trustees identify as Black, one as Asian and one as biracial.

“Being a Black trustee can be very lonely... we found a lot of benefits in our coming together,” says Denise B. Gardner, another steering committee member at the alliance and a trustee at the Art Institute of Chicago who will become its board chair in November. She adds that people of colour now make up 22% of the Art Institute’s 63-person board. Of museums’ recent commitments to equity, Gardner says: “I firmly hope and believe it’s not lip service.”

Denise Gardner, a trustee at the Art Institute of Chicago who will become its board chairman this autumn Lori Sapio/Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Brooke Minto, the executive director of the trustee alliance, says the group plans to publish year-on-year reports measuring Black representation in museum staffing, exhibitions, programming and business operations.

Blatant disparity

Research into the composition of museum staffs stretches back to 2015, when a study by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Ithaka S+R, the AAMD and the AAM found that employees were more racially homogenous than the US population: 76% were white and 24% people of colour, compared with 62% to 38% in the general population.

The disparity “was so blatantly obvious that it was embarrassing,” says Laura Lott, the AAM's president and chief executive. A follow-up study in 2018 “notched up just a bit”, she notes, with 72% found to be white and 28% people of colour. Progress had been uneven: most of the improvement was seen in education and curatorial departments, while hiring for leadership and conservation positions lagged. Overall, 84% of the subset comprising museum leadership, curators, educators and conservators in 2018 were non-Hispanic white.

Correspondingly, the AAMD estimates that 85% of its present 227 member directors are white. Curators also remain overwhelmingly white: the National Gallery of Art, for example, says that three, or 6%, of the 52 employees in its curatorial division are people of colour. Still, that is a gain from one among 47 in April 2020. E. Carmen Ramos, the first woman and person of colour to serve as chief curator, will arrive at the museum in August.

E. Carmen Ramos, who has been appointed chief curatorial and conservation officer at the National Gallery of Art © 2021 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

The NGA, led by Kaywin Feldman since 2019, received an open petition signed by dozens of people last summer accusing the museum of racial and sexual harassment and calling for institutional change. Feldman acknowledged the “tension” while underlining her efforts to make the institution more reflective of American society at large. Her executive team has been transformed from 100% white to 57% Bipoc in just 18 months, the museum says.

Jones of the AAMD and the Crocker Museum suggests that “the biggest problem is unintentional bias” in recruitment, such as insisting on minimum qualifications. “Two years ago, everyone on my visitor services desk had a master’s degree,” she says of the Crocker. In higher positions at museums, she adds, “there was a norm that everyone had to have a PhD, and that has hurt the field historically.”

La Tanya Autry, a Cleveland-based Black art historian and curator who co-founded the activist group Museums Are Not Neutral in 2017, argues that genuine transformation depends on dismantling senior management and board structures. “They say, we’re going to have a diversity chief, yada, yada,” she says. “That hasn’t led to real change; it’s tokenism. The core of the institution remains the same.”

In the midst of a recent curatorial fellowship and residency at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Cleveland, Autry accused the institution of racist practices, a move that she says nearly torpedoed her current exhibition there, Imagine Otherwise, a multimedia show exploring how people of colour navigate anti-Blackness.

The museum disconcerted many last year when it cancelled a show devoted to drawings by the artist Shaun Leonardo depicting Black and Latino victims of police killings. MOCA’s leadership reasoned that the images would be too traumatic, but Leonardo accused the museum of censorship. The controversy ultimately led to the departure of the executive director, Jill Snyder, after 23 years at the helm.

Rather than directing funds to major museums with entrenched power structures, Autry suggests that communities should aid grassroots institutions that have trouble staying afloat, such as Cleveland’s volunteer-run African American Museum, which is in urgent need of repairs, or new organisations like the city’s Museum of Creative Human Art, which runs art classes for underserved communities.

La Tanya Autry, an art historian and curator who was a co-founder of the group Museums Are Not Neutral Museums Are Not Neutral

John Kuo Wei Tchen, a professor of public history and the humanities at Rutgers University and the director of its Clement Price Institute on Ethnicity, Culture and the Modern Experience, suggests that the push for equity and diversity will ultimately be driven by smaller community-based art organisations, not behemoths that “are deeply embedded into structures of wealth and power”. He cites contributions to diverse dialogues by the Studio Museum in Harlem and El Museo del Barrio in New York, for example.

“There’s going to be a crisis of confidence and delegitimising of these very large institutions that are becoming more and more removed from the claims they make of being inclusive and representative and democratic,” Tchen says. “There will be breaking points in the near future in which the claims just won’t match up with the practice. That’s where moments of truth will have to be further resolved.”

Trailblazing acquisitions

One area in which US museums have recently made notable gains is in acquiring works by people of colour. The Baltimore Museum of Art has been a trailblazer: in 2018, it deaccessioned seven works by white male artists, raising $16m to purchase works by under-represented figures. Its current exhibition Now Is The Time: Recent Acquisitions to the Contemporary Collection features 22 of the 125 pieces acquired so far with the $16m in proceeds, by such artists as Betye Saar, Firelei Báez, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Thornton Dial and Fred Eversley.

An installation view of Now Is The Time: Recent Acquisitions to the Contemporary Collection, an exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art Mitro Hood

“I think it’s a very simple value proposition of equity,” says Asma Naeem, the Baltimore museum’s chief curator and a co-organiser of the exhibition. “It’s about engaging with a Black-majority city to be more reflective of the city’s population, and to tell new stories that have previously been excluded from our history.” Eversley, for example, was the only African American artist in the California Light and Space movement, she notes. “Previously those narratives for the BMA had been monopolised by white men.”

The museum’s curators are also conducting a systematic review of its 95,000 objects with the goal of better understanding artists’ histories and putting their works into an enlightening context. “How can we be historically responsible to those artists based on what biographical data we have?” Naeem asks.

Nevertheless, the BMA was thwarted in an attempt last October to sell three blue-chip paintings by white artists, Andy Warhol, Brice Marden and Clyfford Still. The goal was to raise $65m to promote salary equity and audience engagement as well as acquisitions and collection care, after the AAMD temporarily relaxed its policy on deaccessioning. (The proceeds from selling works are normally restricted to buying more art, but the association said in April 2020 that museums could also use deaccessioning funds for “collection care”.) Following protests from former trustees and 15 former AAMD presidents, the museum called off the Sotheby’s auction with hours to spare.

Over the past year, dozens of other museums have made high-profile acquisitions of works by Black and Indigenous artists, such as the Met’s purchase of two monumental paintings by the Cree artist Kent Monkman that it commissioned for its Great Hall, or the recent gift of works by Southern self-taught artists to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Many institutions have made diversified collecting a top priority: among the 24 artists whose work the Whitney has acquired since last June, it says that 23 identify as people of colour or female.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) points to Jean Pigozzi’s 2019 gift of 45 contemporary works by artists based in Africa, the museum’s 2020 purchase of 55 prints of photographs by Gordon Parks and its 2019 acquisition of 13 performances by Pope.L. Last year, the NGA acquired its first painting by a Native American artist, I See Red: Target (1992) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, as well as 40 works by 21 African American artists from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. Still, the museum acknowledges that only around 1% of the works in its collection are by US artists of colour.

Museums are also adjusting the labelling and interpretive strategies for their collections so they can tell more diverse stories. The J. Paul Getty Museum’s antiquities department, for example, is revising its online descriptions of Greek, Etruscan and Roman artefacts depicting Black Africans. Many of the descriptions “overlooked issues of race, gender, violence, and enslavement”, the curators wrote in a blog post. “This silence is dangerous, as it leaves space for anachronistic assumptions and stereotypes to flourish.”

Rapid-response curating

As long-planned exhibitions devoted to Black or biracial artists have come to fruition—the travelling Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, now headed to the Phillips Collection; Bisa Butler: Portraits at the Art Institute of Chicago and Julie Mehretu at the Whitney, to name a few—museums are also learning to pivot more quickly in response to real-world events.

It took the Speed Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, just four months to organise Promise, Witness, Remembrance (until 6 June), an exhibition reflecting on the life of Breonna Taylor, her killing by Louisville police officers in March 2020 and the year of protests that followed.

When a Black Trans Lives Matter march and rally drew an estimated 15,000 people into the streets of Brooklyn as well as the grounds of the Brooklyn Museum last June, MoMA quickly arranged to stream Salacia, a video it had just acquired by the filmmaker and activist Tourmaline, on its website. The work reimagines the life of a 19th-century trans woman in Seneca Village, a Black community that was demolished to make way for Central Park.

“It was a way for us to engage on an issue that was clearly important for the community,” says Stuart Comer, MoMA’s chief curator of media and performance. “We didn’t have to wait for years—we could share it in the moment.” (MoMA says 44% of its staff of 734 and 20% of its 30 curators identify as people of colour.)

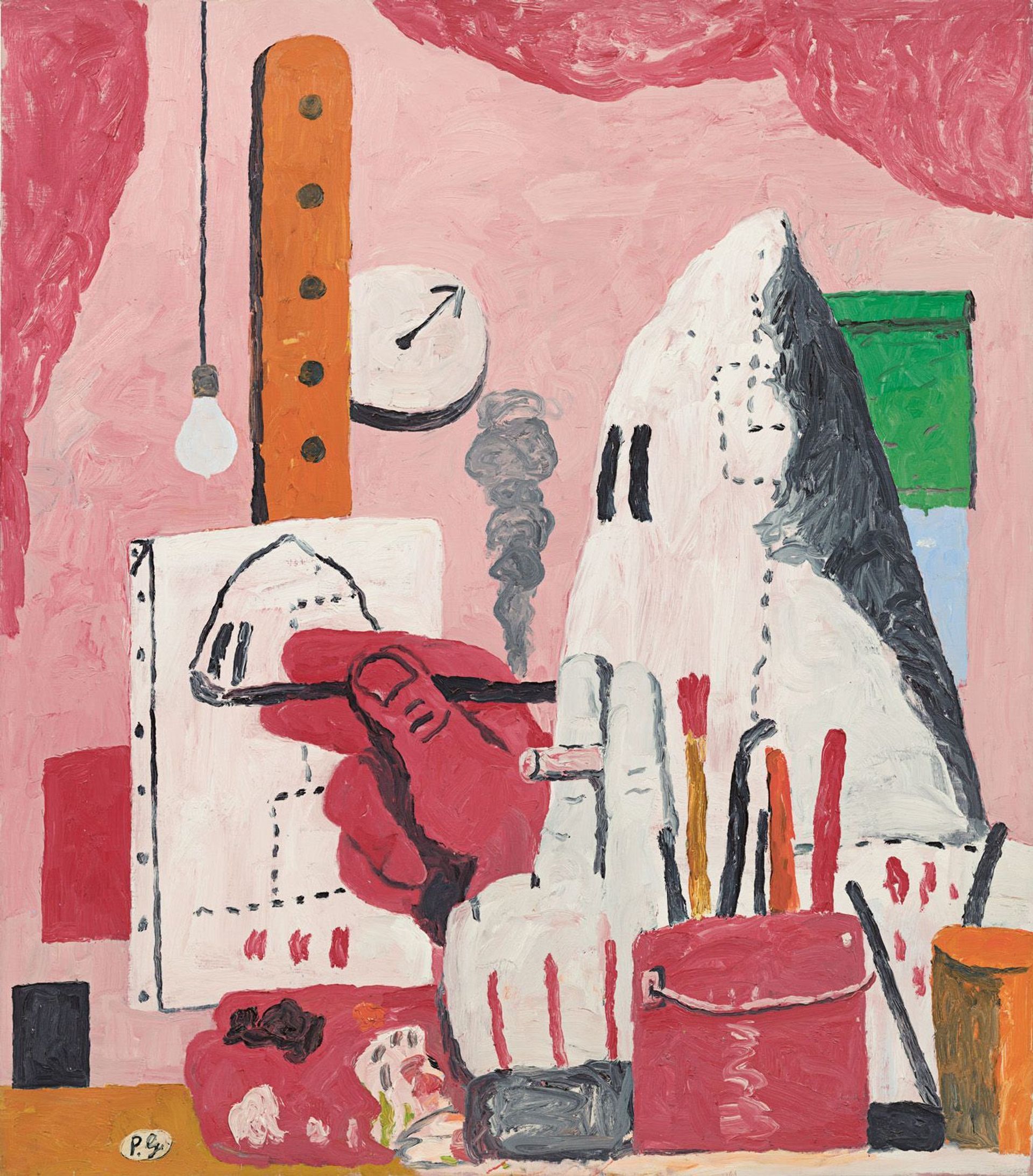

Yet in some cases, racial justice concerns have compelled museums to slow down. The NGA, the Museums of Fine Arts in Boston and Houston and Tate Modern in London deferred a travelling retrospective devoted to Philip Guston last September, citing concerns that his Ku Klux Klan imagery could offend visitors. The decision stirred accusations of censorship in the art world, with many noting that Guston was a vigorous proponent of social justice. With revised context for the images, the show is now scheduled to open in May 2022 in Boston.

Philip Guston's The Studio (1969) © The Estate of Philip Guston

Building community trust

Perhaps the biggest challenge that American museums face is diversifying their audiences. The latest study by the AAM, from 2010, found that on average 6% of museum visitors were African American. A 2017 survey commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts found that 27% of white adults in the US had visited a museum or gallery over the previous year, compared with 17% of Black adults.

The Guggenheim’s diversity, equity, access and inclusion plan cited a 2018 study that found that 73% of its visitors were white, while just 43% of New York City’s residents were. To attract more diverse audiences, “we’ve had a calibration of content,” Armstrong says, referring to the museum’s current exhibition of photography of Black subjects by Deana Lawson, the winner of the 2020 Hugo Boss prize, and Off the Record, a show of contemporary works that challenge dominant cultural narratives. The museum also points to an immersive project presented in its rotunda featuring the Rwandan-born Christian Nyampeta.

Chief, a photograph by Deana Lawson, winner of the 2020 Hugo Boss Prize. The work is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum © Deana Lawson, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

A survey conducted by the NGA in February 2020 found that 70% of that month’s visitors identified as white and a majority were 55 to 75 years old. The museum, which reopened on 14 May after two pandemic closures, has since rebranded itself as an institution “of the nation and for all the people” to emphasise inclusiveness.

The MFA in Boston contended with controversy over a 2019 field trip in which a group of Black middle school students and chaperones reported being racially profiled and closely followed by security guards and being hissed at by a white patron. After an investigation, the museum reached an agreement with the Massachusetts attorney general to embrace new policies and set up a $500,000 fund to promote diversity and inclusion.

Rosa Rodriguez-Williams, who was appointed the MFA, Boston’s senior director of belonging and inclusion last September, says her job is mostly visitor-focused: “really building trust with communities”. Growing up Latina in the Boston area and visiting the MFA on school trips, “I knew this wasn’t a space for me because a lot of people I saw didn’t look like me or my parents,” she says. Today, she says, she is heartened by offerings like the current exhibition Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation. (The MFA says that the percentage of staff members who identify as Bipoc has increased from 21% to 30% since 2017, and that of its 37 curators, 11% now do as well.)

Rosa Rodriguez-Williams, the senior director of belonging and inclusion at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

For the Brooklyn Museum, the quest for outreach has meant meeting with community organisations throughout the borough to determine how it can support their work, partnering with groups on food relief and “casting ourselves as an anti-racist museum”, says Keonna Hendrick, the director of diversity, equity, inclusion and access.

The institution has been labouring for years to welcome more diverse populations in Brooklyn, including African Americans, people of Caribbean descent, African immigrants and Latinos. In addition to highlighting the work of Black artists across the African diaspora, Hendrick says the museum tries to “create a space for people to come as they are” and “just have a really good time”. She praises the museum’s guards, who “smile at you and lead you in the space rather than police you”.

Keonna Hendrick, director of diversity, equity, inclusion and access at the Brooklyn Museum Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

Several years ago, the J. Paul Getty Museum approached arts and community groups in the Los Angeles area to encourage their Bipoc and LGBTQ members to participate in openings and other activities. In 2020, it launched a virtual classroom partnership with the Los Angeles Unified School District, in which more than 90% of students identify as Bipoc or Latino. (The Getty says that 29% of its 204 employees are non-white.)

“Neither the Getty Villa nor the Getty Center is well served by public transport, and that is a great pity, especially for transit-dependent communities,” says Timothy Potts, the museum’s director. As a result, he says, the education department financed bus links and docent-led tours for more than 154,000 students from underprivileged schools in 2019. Then came the pandemic, which closed US museums and still generally makes group visits an impossibility.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which estimates that 49% of its 464 employees and 42% of its 57 curatorial staff members are people of colour, has collection-sharing and exhibition partnerships with smaller museums in the area to widen access to underserved communities. During its year-long closure, it provided virtual school field trips, and it is now offering family activity videos in six languages as well as the talks programme Racism Is a Public Health Issue.

Truth and reconciliation

Some experts suggest that museums must fully reckon with their own histories of inequity in order to atone for them.

The Met pledged in its diversity plan to publish a public report investigating its racial history and current practices, although Weiss says the research has not yet begun. In March, the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore released an expanded account of its founders’ support for the Confederacy: Henry Walters and William Walters both profited from racist labour practices before and after the Civil War, the museum now admits.

The Walters also acknowledges on its website that the founding bequest reflected “the typical Eurocentric worldview that drove collecting at the turn of the 20th century in the United States and across Europe” and “biases that the museum field continues to grapple with today”. The museum has pledged to study the provenance of its collection and make those histories accessible to visitors in person and online.

Some cultural institutions want to “skip the truth phase and move straight to the reconciliation phase,” says Lori Fogarty, the director and chief executive of the Oakland Museum of California. “But it’s important to understand the history.” (Her museum, located in one of the country’s most diverse cities, estimates that 56% of its visitors were people of colour in 2019. People of colour make up 37% of the museum’s staff, 40% of its board and three of its four curators, it adds.)

The nascent efforts at self-examination parallel the recent tumult at American colleges, universities, libraries and other institutions founded by wealthy white benefactors in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Many are acknowledging a historical complicity with white supremacy.

“This is how museums were established—with those values and with that structure in mind—which is perpetuated today with an over-reliance on private philanthropy, which gives power to wealthy people who are disproportionately white,” notes Lott of the AAM. “We’re pausing a little bit to look back and really understand what damage we’ve done.”