The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) announced today that the collector and photographer Jean Pigozzi was donating a “transformative” gift of 45 works of contemporary African art to the museum, positioning MoMA to become a “unique institutional leader” in the field.

Glenn Lowry, the museum’s director, said in a statement that the gift would play an important role in the ambitious re-installation of MoMA’s permanent collection, which is taking shape as the institution prepares to reopen on 21 October in expanded galleries. The museum has cast the rehanging as an opportunity to rethink the entire history of Modern and contemporary art, highlighting and juxtaposing artists of more diverse backgrounds and geographic origins.

Among the highlights of Pigozzi’s gift, says Sarah Suzuki, drawings and prints curator, is Alphabet bété (1991), a “truly magnificent landmark work” in which the Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré created a pictographic alphabet with 449 individual drawings. “He tried to capture all of the aural sounds that are made across language systems,” she said, with the idea of creating “a tool for universal communication”.

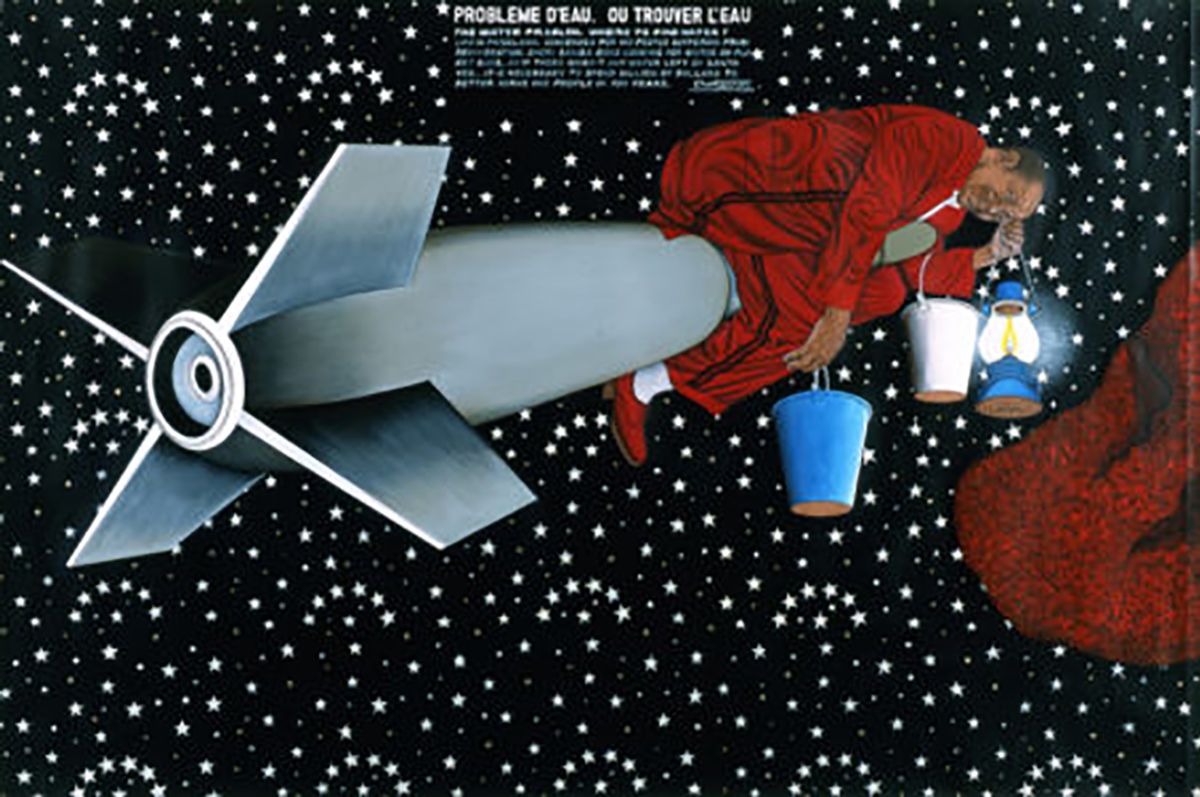

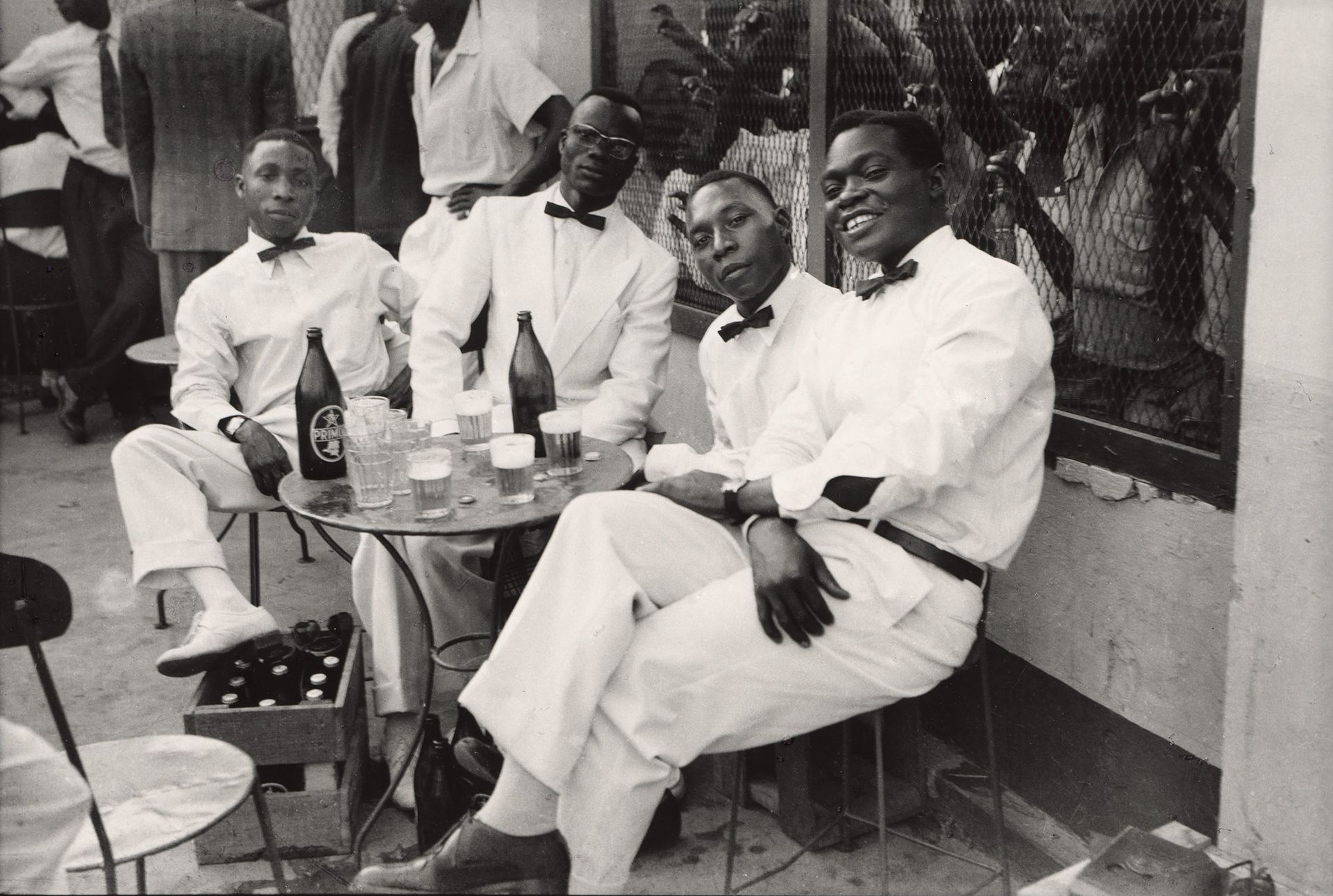

Other standouts include Water Problem (2004), Chéri Samba’s environmentally themed painting of a celestial sky in which holographic stickers form stars and the Congolese painter himself rides a rocket in space looking for new sources of water. And, reflecting Pigozzi’s passion for the medium, there are photographs by such artists as Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, Ambroise Ngaimoko/Studio 3Z and Jean Depara.

Jean Depara's The Musicians (1975)

Also among the collecting coups are four sculptures by Bodys Isek Kingelez, a Congolese artist who was the focus of a MoMA retrospective that Suzuki organised last year with Pigozzi’s involvement but was not represented in the museum’s collection. “His work is extraordinarily hard to come because of its fragility,” the curator says: one treasured promised gift she cited is a cityscape from 1994 that is an hommage to the agricultural village where Kingelez grew up, remade as a utopian supercapital.

Suzuki says that Pigozzi started collecting in 1989, when he was “gobsmacked” by Magiciens de la Terre, a “truly global” exhibition of artists from more than 50 countries at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. With the help of the curator André Magnin, he went on to form one of the world’s biggest collections of contemporary African art in private hands, the Contemporary African Art Collection (CAAC), although he has never visited the continent himself.

MoMA worked closely with Pigozzi on selecting the 45 works that would best resonate with the museum’s holdings, Suzuki says. Part of what makes his collection unusual, she adds, is that it is made up of artists who have not worked primarily within the Western system of museums and galleries.

Suzuki parried when asked which works donated by Pigozzi might be included in the reinstallation of MoMa’s permanent collection, and thereby help to recast the history of Modern and contemporary art.

“We’re not disclosing installation plans at the moment,” she says. “We’re looking forward to unveiling the totality in October.”

• For an interview with Jean Pigozzi, read In search of art out of Africa: an interview with Jean Pigozzi