One of the artist collectives shortlisted by Tate for this year’s Turner Prize has condemned the institution for exploiting Black artists and artists of colour.

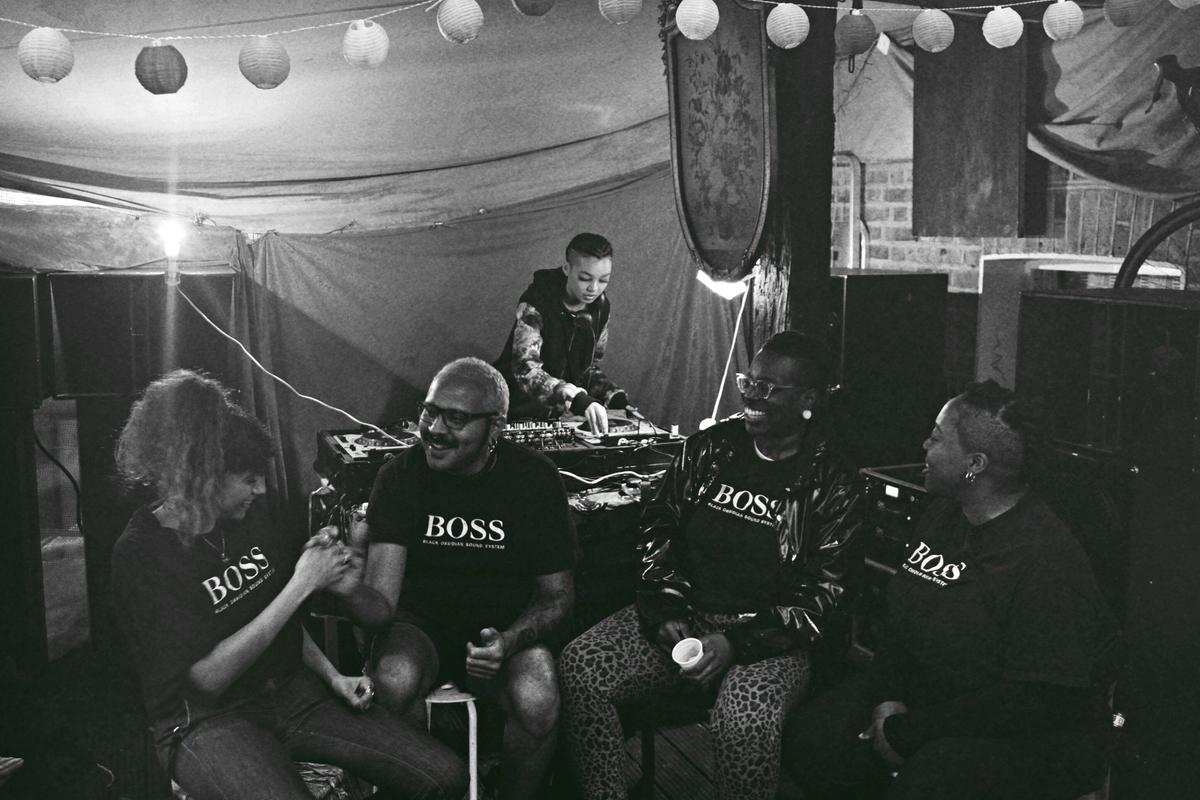

In a wide-ranging statement published on instagram yesterday, Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S.), a group set up in London in 2018 to bring together “a community of queer, trans and non-binary Black and people of colour involved in art, sound and radical activism,” noted the “exploitative practices” underpinning the Turner Prize and “prize culture” in general; accused Tate of failing to support artists whose work it displays; condemned the museum’s handling of sexual harassment accusations against one of its most important patrons as well as its response to strikes organised last year by Tate staff whose jobs were cut because of the pandemic.

B.O.S.S. acknowledges that it is “grateful” to have been shortlisted for the Turner Prize and for the “recognition of our work as a collective”. It also notes that it will participate in the prize but it adds that “it is important for us to name some of the inconsistencies” of this accolade. It then accuses museums like Tate of embracing social artistic practices without adequately supporting the artists and groups they are claiming to champion.

“Although we believe collective organising is at the heart of transformation, it is evident that arts institutions, whilst enamoured by collective and social practices, are not properly equipped or resourced to deal with the realities that shape our lives and work. We see this in the lack of adequate financial remuneration for collectives in commissioning budgets and artist fees, and in the industry’s in-built reverence for individual inspiration over the diffusion, complexity and opacity of collaborative endeavour,” B.O.S.S says.

It also condemns the amount of time given to shortlisted groups to prepare work for the Turner Prize exhibition which takes place this year at the Herbert Art Museum in Coventry from 29 September to 12 January 2022.

“The urgency with which we have been asked to participate, perform and deliver demonstrates the extractive and exploitative practices in prize culture, and more widely across the industry—one where Black, brown, working class, disabled, queer bodies are desirable, quickly dispensable, but never sustainably cared for.”

The Turner Prize shortlist this year consists of five grassroots organisations which “work closely and continuously with communities across the breadth of the UK to inspire social change through art,” Tate said on 7 May, when it announced the nominated groups, adding that the “collaborative practices selected for this year’s shortlist also reflect the solidarity and community demonstrated in response to the pandemic.”

Despite this statement of support for communal action, B.O.S.S. notes that “over the last year, there have been strike actions at several art institutions, including the sponsor of the Turner Prize, Tate, protesting the redundancies staff have been forced to take. It is not lost on us that the collective action of workers coming together to save their jobs and livelihood was not adequately recognised by Tate.”

Tate Enterprises, the commercial arm of the museum which operates retail, catering and publishing services at the four Tate galleries in London, Liverpool and St Ives, made 295 people redundant last year because of the pandemic. In December, Tate also announced plans to cut its own workforce by 12%, equivalent to 120 full-time roles.

Finally, B.O.S.S. refers to Tate’s handling of sexual harassment accusations against the retired dealer and collector Anthony d’Offay who gifted and sold an important contemporary art collection to Tate and the National Galleries of Scotland in 2008. The accusations first emerged in the Observer newspaper in January 2018 and Tate’s critics accuse the gallery of dragging its feet in severing ties with d’Offay while publicly proclaiming it had already done so in response to the revelations. It also expresses solidarity for the artist Jade Montserrat who has publicly accused d’Offay of racist, sexual and inappropriate behaviour and repeatedly raised these issues with Tate. D’Offay strongly denies all accusations against him.

“We understand that we are being instrumentalised in this moment. We ask ourselves: how can a BPOC queer collective of artists and cultural workers be nominated for the Turner Prize whilst Black women artists continue to be silenced?...It is crucial that we acknowledge the context from which our participation emerges. We demand the right to thrive in conditions that are nurturing and supportive.”

In a statement sent to The Art Newspaper, Tate responded to some of the points made in B.O.S.S.’s instagram post.

“Tate is committed to championing the work of artists and we always welcome critical dialogue and engagement. Artists must be free to express themselves and share their views however they wish. The Turner Prize jury were passionate about the work of all the collectives they shortlisted, recognising that these collaborative practices reflected the solidarity and community demonstrated across the UK in response to the pandemic. The jury, Tate and the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum are delighted Black Obsidian Sound System accepted the nomination.”

“Both the team at the Herbert in Coventry and Tate want the collectives to feel supported and look forward to working with them on the Turner Prize exhibition over coming months. Given the larger number of artists involved in the prize this year, all the shortlisted collectives are each receiving £10,000 for their participation rather than the £5,000 given in previous years.”

Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain and the chair of the Turner Prize jury, noted last Friday that “one of the great joys of the Turner Prize is the way it captures and reflects the mood of the moment in contemporary British art.” That observation has turned out to be prescient, just not the way Tate was expecting.