Lucy Raven’s protean, multidisciplinary practice defies simple definition. Over the past two decades, the Arizona-born, New York-based artist has drilled into the American bedrock and filmic history through experiments in light and moving image. Two new commissions for Dia Chelsea’s grand reopening—after a two-year, $20m expansion—boldly question the Land Art legacy Dia exists to enhance. Casters is a version of the slowly revolving spotlight installation Raven first showed at London’s Serpentine Gallery in 2016. Ready Mix, meanwhile, is an immersive projection of mesmeric black-and-white footage showing aggregate and cement being churned into ready-mix concrete. From extractive industries to industrial networks, Raven consistently focuses on the through-lines of a global economy etching itself into the landscape.

Raven on the set of her new film for Dia Chelsea, Ready Mix Photo: Charles Eshelman/FilmMagic

The Art Newspaper: You shot Ready Mix in a concrete processing plant in Idaho. In the accompanying materials, the film is described as contending with the myth of the frontier perpetuated by traditional Westerns. What does the film stem from?

Lucy Raven: I’m from [Tuscon] Arizona. As a kid, my dad would bring us to New York, where he is from. I really didn’t understand why he’d ever moved to the desert: I just wanted to come back here. Later, when I actually moved here, I began to see how the [American] east looks at the west. This project, and maybe quite a lot of work I’ve made, is an exploration of the fantasy of the west. I don’t really like Westerns. I find them quite boring; there are never any interesting female characters; it’s just dusty. This was more about how the west has been developed—the infrastructure necessary to quite literally pave over this so-called empty wilderness, which of course was populated.

It all started through a residency I did in the Philippines several years ago. I flew into Clark air base, [which had been] the biggest American military base outside the US. While there, I thought about how the late 19th-century American colonisation of the Philippines—not something I ever learned about in school—is not an aberration but rather part and parcel of the American doctrine of manifest destiny, and the so-called settling of the west. When California was, essentially, full, and the frontier declared closed, the purchase of the Philippines along with Puerto Rico and Guam happened, in 1898. All these forms of state architecture and concrete infrastructure in Manila came along at that moment too. So when I got back to the States, I decided to get kind of literal, and do a site visit at a concrete plant.

Why Idaho?

My partner and I have a cabin there. And in movie terms, Idaho is a kind of stand-in for the west in general. I also realised that if I made a concrete film in New York, it would be like a mob film so I knew I had to make a Western, out west.

The camera’s perspective and decisions are intriguingly tangible in the footage. Did you conceive of the camera as a character?

You know, we have musique concrète, concrete photography, concrete poetry. Going into this project, I wondered, what might the term “concrete cinema” mean? Instead of naturalising the eye of the camera, I thought about it choreographically. The drone shots, for example, are not shot the way a drone operator normally would: it’s almost misuse. Similarly, in order to shoot these flows and pourings of raw materials, you would usually use a higher frame rate, because it is all moving so fast. But I was really interested in that blur, the in and out of focus.

Aerial shots in Ready Mix were “not shot the way a drone operator normally would: it’s almost misuse”, Raven says © Lucy Raven; courtesy of the artist

Certain scenes in Ready Mix bring to mind the surprising abstract paintings of, say, Michael Heizer. Were you consciously making a connection between Abstract Expressionism, and what the Land artists made in the desert?

There ended up being so many sections that I now think of as, like, the Frankenthaler scene, the Pollock scene, the Heizer spill. While filming, though, I wasn’t thinking about that. It isn’t something you usually think of when you think about Land Art.

Of course, the big three—James Turrell’s Roden Crater, Michael Heizer’s City and Charles Ross’s Star Axis—are all nearing completion. Your work feels like an important counterpoint to these big, very male, very white projects, be that when you speak about the myth of the west or when you speak about Westerns having no strong female characters, given the women who have played central roles in, say, City, yet remain overshadowed.

I think about this a lot, having visited many of those sites, and seen the caretaking that goes into maintaining them. Ready Mix has a monumentality to it, in the way it will be projected, and also within the image itself. But it is not an imposition on to the landscape, which those works are. My question is, whose perspective is being projected there? I’ve always thought of works by, for example, Walter de Maria, as having a kind of violence to them. But it wasn’t until I visited [his 1977 work] The Lightning Field last year that I began to understand why. First, I hadn’t ever really internalised that all those poles are spikes. But also, the violence is in the very grid he’s laying out—it’s a Cartesian projection on to the landscape, and a neutrality that’s hard to parse. Is the work about the violence, or is it enacting it? I think that question is provocative.

Abstract Expressionism, and Land Art, of course, dealt in universality. But you’re making abstract images with raw materials that have been mined as resources, and are sold as commodities. You have referenced Robert Smithson’s idea of the exhaustion of the landscape. With Ready Mix are you delving into the kind of specifics those movements did not address—that is, whose land is being depleted? Who has been robbed of resources?

This notion of private property became quite central in Ready Mix. On one side, you have the development of public infrastructural projects. And on the other, you have what’s called the Dawes Act of 1887: the development of private property and the disenfranchisement of the indigenous peoples who lived there to begin with. Concrete is tied to the creation of private property, which immediately leads you to the protection of private property, which circles back to the police and the militarisation of protecting private property, and to the beginnings of film-making too—because those histories are so deeply intertwined. All of which is what Casters came out of.

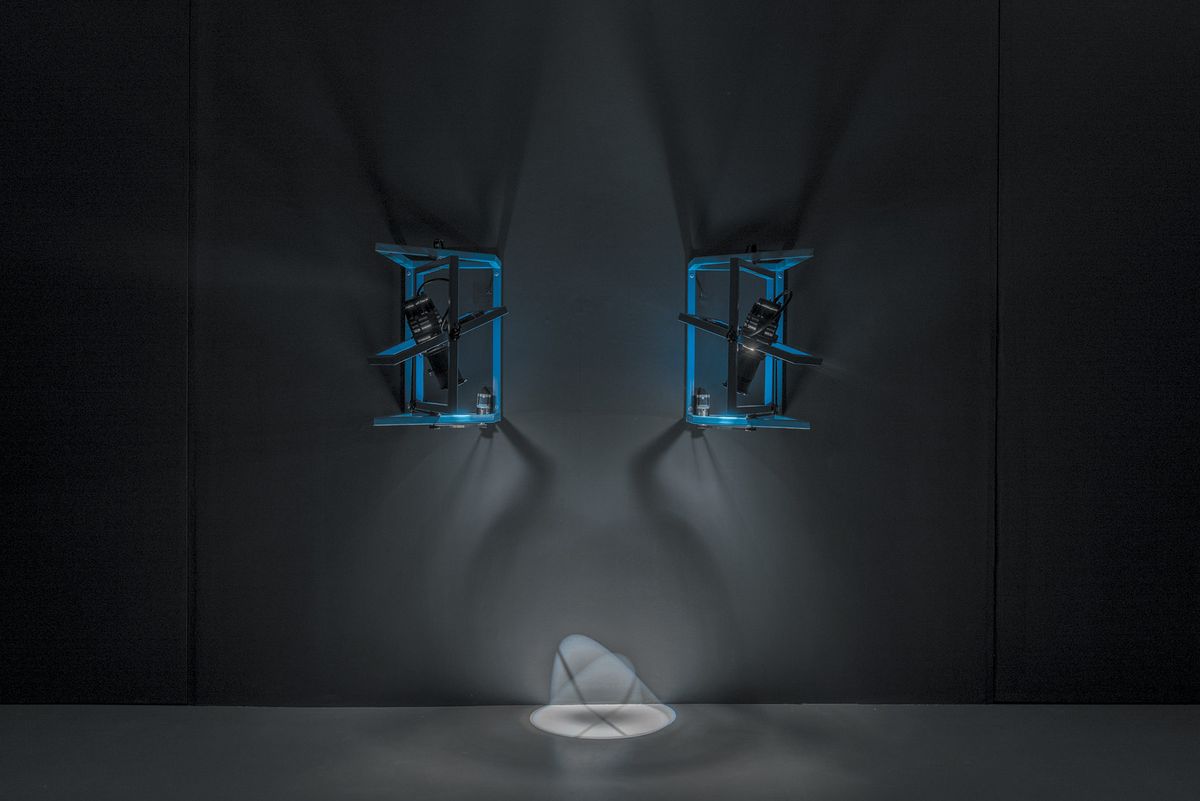

This new iteration of Casters involves two pairs of moving spotlights on customised armatures similar to roto-casters—devices used to mould objects in the round. What was the impetus for this work?

Casters evolved from a previous 3D film entitled Curtains, [as well as] Tales of Love and Fear, which involved these two counter-rotating projectors. I was thinking about Robert Smithson, but also Michael Snow’s 1971 film, La Région Centrale. Snow, a Canadian structural film-maker, had this idea to make a kind of total or absolute record of the landscape. He used an articulated robotic arm to shoot the view from the top of a mountain in Quebec. When you watch it, you’re watching the horizon spinning, slowly. I wanted to see if you could have a record of a place that was absolute at the site of reception, rather than production. I was interested in liberating the medium from the frame. In its first iteration, Casters felt like the beginning of a way of thinking about light and motion that I knew I’d been looking for.

The light becomes a presence in the room and a way to describe that physical space too. Is there a bodily aspect to the piece, for you?

Another starting point was a visit I’d made to the rock-cut temple of Ajanta in India. The temple is filled with all these paintings, which you can only observe by flashlight. You end up with this haptic connection between what your hand is holding—a light—and what your eye can see. There is something about touch, and physicality, in Casters. And then there’s the carceral aspect: searchlights, much like the amplified slip rings used in Snow’s piece and in the Casters machines (to allow for 360º rotation without the wires getting tangled), evolved out of military equipment.

The lights’ tracing is relentless, ominous, inescapable. How did you determine the patterns they would follow?

I knew what I wanted these things to do. And my friend Robert de Saint Phalle made it happen. I was thinking about the spiral animations John Whitney made for Alfred Hitchcock’s [1958 film] Vertigo, which are thought of as the first computer animations. We made rudimentary visualisations to figure out patterns and pacing. But here too, it is a kind of choreography, and as such needs to be staged and programmed in the space itself. It is tricky to get something to move super slowly and really smoothly.

And those mechanisms determine what it sounds like in the space too?

Exactly. Like, how loud is too loud? The other way I’ve been trying to think about the movement has been through drawing. Particularly during the pandemic. They started out as technical drawings and then became their own thing—a non-linguistic way for me to think through ideas about light and speed in space.

Biography

Born: 1977, Tucson, Arizona.

Lives: New York

Education: 2008 MFA, Bard Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts, Annandale-on-Hudson; 2000 BFA studio art, BA art history, University of Arizona, Tucson; 1999 Escola Massana, Centre D’Art i Disseny, Barcelona

Key shows: 2019 Bauhaus Museum, Dessau; 2018 Los Angeles County Museum of Art; 2016 Serpentine Galleries, London; 2014 Portikus, Frankfurt; 2012 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; 2012 Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Not currently represented

• Lucy Raven, Dia Chelsea, New York, 16 April- January 2022

• Read Linda Yablonsky's review of the exhibition here