Re-emerging as a force in Chelsea after a two-year, $20m renovation, the Dia Art Foundation’s space there will reopen on Friday (16 April) with a renewed purpose: to champion under-recognised artists and to serve as an information hub for all 11 of Dia’s long-term art sites.

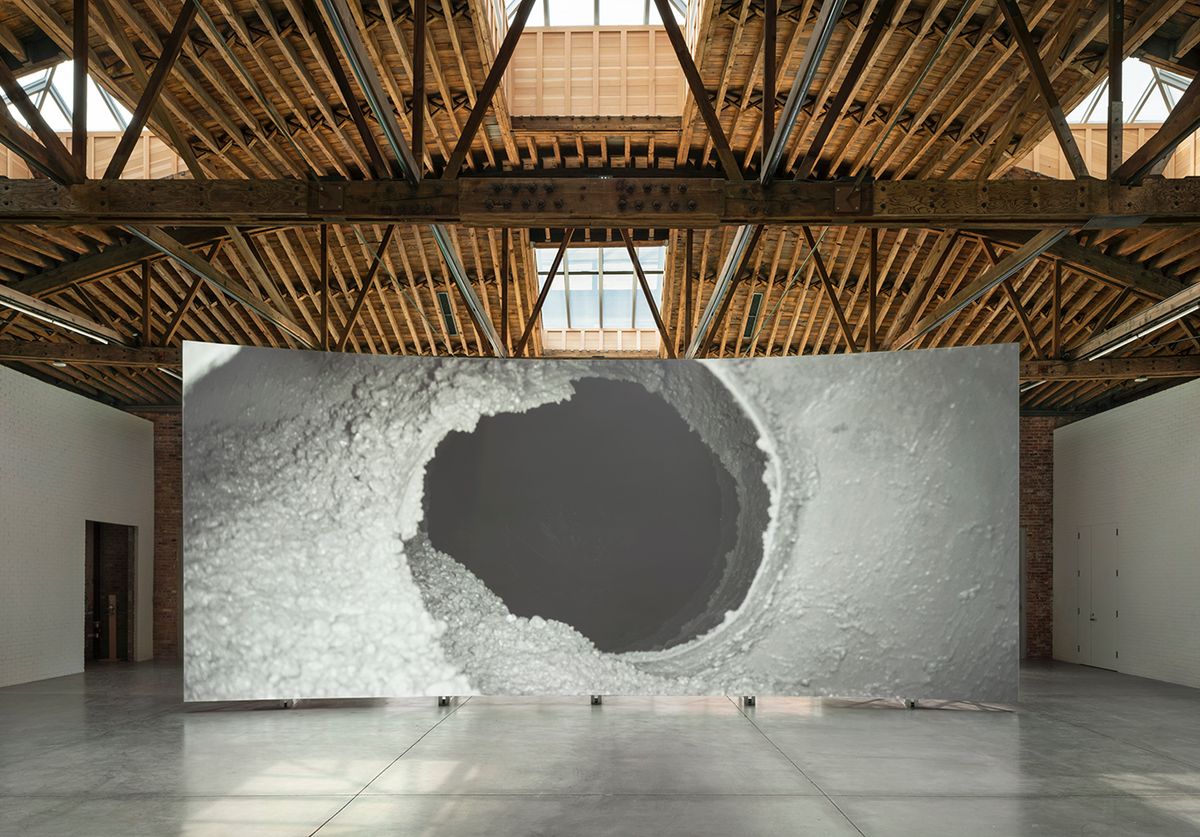

The foundation’s Chelsea renovation unites its three contiguous buildings on West 22nd Street and underlines its gritty history of inventively revitalising existing structures. The 32,500 sq. ft project, which includes 20,000 sq. ft for exhibitions and other programming, embraces the neighbourhood’s traditional character and architectural vernacular, with wide-open industrial-style spaces, exposed brick, wooden ceiling beams and rehabilitated skylights that allow natural light to pour in and illuminate the art. It also reasserts the foundation’s importance in championing long-term art installations that flood the senses.

Dia’s goal in the revamped Chelsea space is to keep artists’ works on display for as long as nine months or more, beginning with a film and two pairs of light sculptures commissioned from the artist Lucy Raven. Her black-and-white 50-minute film Ready Mix, shot at a plant in Idaho, records the transformation of minerals and binders into concrete and evokes the historical preoccupation of several Dia artists with the American West; the lights in her sculptures, part of a series titled Casters, will move continually in and out of synchronisation with each other in a cavernous space.

A scene from Lucy Raven's film Ready Mix, 2021 © Lucy Raven, courtesy of the artist, Dia Art Foundation, New York

Lucy Raven, Casters X-2 + X-3, 2021 Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, courtesy of Dia Art Foundation

Jessica Morgan, the nonprofit foundation’s director, notes that Raven is not represented by a dealer. “We’ve always tried working with curators on what artists we can make a difference with,” she said in an interview, “what does not align itself so easily with gallery representation for one reason or another, and therefore needs space, needs support, needs funding.”

For the Dia Chelsea renovation, Morgan says she consulted artists whom Dia had sponsored in the past, including Zoe Leonard and Roni Horn, about their instincts for the site. “They both were very clear about the humility of the industrial spaces that we use: they’re not spaces that compete with that work,” she says. “They were definitely not encouraging any move toward new building,” but “rather thinking about what we have and using that most effectively.”

To that end, Morgan enlisted the firm Architecture Research Office (ARO), whose projects have included the restoration of Donald Judd’s former residence and studio in SoHo and of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, to lead the design and construction while keeping costs down. “They've been just so thoughtful, but also understanding of what our goals were ultimately with the spaces–which was to try and keep them looking as close as possible to their original state, which isn't necessarily the most exciting thing for an architect,” she says.

The sidewalk view of Dia Chelsea, with its uniform brickwork uniting three spaces Dia Art Foundation

One result is the creation of a united brick façade for all three buildings that evokes the brickwork at Dia Beacon, the foundation’s sprawling exhibition space in a converted Nabisco factory on the Hudson River, 55 miles north of New York City. (Two of the Chelsea buildings were purchased in the 1990s, and the one linking them in 2011.)

Two mammoth galleries in Chelsea will operate, and the overall space will be open even while installations are being dismantled, inviting visitors to a bookshop, reading room, “talk space” and one full storey for educational programming, Morgan says. Office spaces have also been expanded and renovated. The bookshop, a reincarnation of one in a previous Chelsea space, celebrates the historic role of Dia’s publications in promoting its programming as well as more recent forays into commissioning poetry, fiction and critical essays.

Admission in Chelsea will be free, as it is at all of the foundation’s New York sites; Covid-19 restrictions will still limit visitors to 25% capacity, and groups are not yet allowed.

ARO is also overseeing projects like the planned renovation of a Dia space on Wooster Street in SoHo, which is now being leased but is destined to be a 2,500 sq. ft exhibition venue due to open in the autumn of 2023; the renovation of two nearby Dia installations by Walter De Maria, The Broken Kilometer (1979) and The New York Earth Room (1977), which are also due for completion in 2023; and the restoration and expansion of the lower level and surrounding landscape of Dia Beacon, for which no timeline has been set.

Jessica Morgan, director of the Dia Art Foundation Photo: Gabriela Herman, courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York

The initiatives are part of a $90m capital fundraising campaign, with $80m raised so far by the foundation, according to Morgan. In addition to financing the renovation and construction projects, the foundation hopes to boost its endowment, currently at $85m, to $100m, she says.

Nathalie de Gunzburg, chairman of Dia’s 24-member board of trustees, says the board has provided most of the $80m raised so far. “We’re doing quite well,” she says, despite the economic downturn precipitated by Covid. De Gunzburg and Morgan both note that Dia is not largely dependent on ticket income and therefore did not suffer from the precipitous decline in revenue experienced by many art institutions.

A forgivable $1.25 m Paycheck Protection Program loan from the federal government helped Dia cover employees’ salaries during its Covid-19 closures at various sites last year, de Gunzburg says. After furloughing 86 employees after the pandemic last March, they returned in staggered phases as sites reopened, the museum says, while the jobs of three employees in the bookshop, on the curatorial staff and in development, were cut. Morgan says Dia now has 140 employees—“a lean team”—spread over its 11 sites.

The Chelsea opening is an affirmation of the role that Dia has historically played in the area, where the foundation first established a presence in the 1980s. Back then, it was a declining industrial area populated by warehouses and garages, and Dia, Gagosian gallery and the Kitchen were the art pioneers. Dia had a space across the street from the buildings it owns now and was a pathbreaker in promoting work by such artists as Dan Graham, Dan Flavin and Jorge Pardo.

While Chelsea is of course today the premier weekend mecca for New York gallery goers, some galleries are now questioning their commitment to the area as others decamp for neighbourhoods like TriBeCa in search of more space.

Donna De Salvo, the former deputy director and chief curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, joined Dia last year as a senior adjunct curator for special projects. It was a homecoming for her, as she had worked as a curator there in the 1980s, when Chelsea was “a ghost town”, as she puts it, and Dia led the way for the rest of the art world in planting roots.

She casts the Chelsea reopening as a reaffirmation this history while also embracing a “continual redefinition and expansion of the artists we work with”. Like the installations and acquisitions at Beacon, in which she is now playing a big role, De Salvo says, “it gives us an opportunity to rethink different histories and write new histories”, while endeavouring to “see art in the context of the world”.

Founded in 1974 as a kind of counter-museum that would support contemporary artists’ projects, and eventually encompassing Land Art wonders like Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake (1970) and Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973-73) in the Utah desert, Dia is known for its commitment to prolonged meditative viewings of art. Its name comes from the ancient Greek word for “through”, linking the foundation to the idea of a passage or conduit for artists seeking an outlet for creative expression.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty (1970) © Holt/Smithson Foundation and Dia Art Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: George Steinmetz, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

Over the years it has expanded its collection, acquiring additional works by the 1960s and 1970s figures it first championed while embracing later artists who mesh with a philosophy of putting viewers in touch with a wider reality.

When Morgan took over as Dia’s director in 2015 after serving as a curator at the Tate Modern in London, the foundation had relinquished its position as an art force in Chelsea and was leasing its 22nd Street spaces to generate income. Dia Beacon, which had opened in 2003, had meanwhile risen in stature and was attracting enthusiastic young audiences with its mix of mammoth permanent installations like Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses (1996) and temporary viewings like a 2014-15 retrospective of Carl Andre’s sculpture, poetry, works on paper and assemblages.

“When I started, my feeling was, we have these spaces” in New York City and “we need to figure out exactly what we want to do,” Morgan says. “And why don’t we do that through programming, so we can at least get a sense of what works we want and where we ultimately want to land?”

In addition to its three buildings on West 22nd Street, The Broken Kilometer and The New York Earth Room, the foundation’s New York City sites include Max Neuhaus’s Times Square (1977), a sound work on a pedestrian plaza in that area; and Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks), a series of pairings of basalt stone columns and trees adjacent to Dia Chelsea that have grown in number with the galleries’ scheduled reopening.

A pairing in Joseph Beuys, 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks) © Joseph Beuys/Artists Rights

Morgan’s reflections led to a series of artists’ installations in the Chelsea galleries from 2016 to 2019, culminating in a viewing of Holt’s Holes of Light (1973) and Mirrors of Light 1 (1974) tied to Dia’s acquisition of Sun Tunnels. Then the galleries closed for the two-year renovation.

In the art world, “certainly, when I started, there had been this obsession about coming back to Chelsea, and about what was going on with Dia” after the ascendancy of the Beacon outpost, Morgan says. “I think there was a lot of mystery about it. It was a bit of mystery to me, too. And to a large extent, I’d say those questions seem to evaporate, the more we’re doing.”

Linda Yablonsky, The Art Newspaper's contemporary art critic in New York, says Dia’s historic role still reverberates, decades after it cemented Chelsea’s art world status in the 1980s and 1990s when many galleries were weighing a move from SoHo.

“Its advantage over galleries and museums was that it could keep solo shows on view for an entire year—a great luxury (as was the space of its building) that focused attention on each artist in a very particular way,” she says, referring to its earlier space across West 22nd Street. “The installations by Jenny Holzer, Robert Irwin, Robert Gober, Jessica Stockholder, Juan Muñoz, Richard Serra—I think of all of these as high points in my life as a viewer.”

For years, the governance of the Dia Art Foundation was uneven and at times contentious, with trustees sparring over goals and finances and directors abruptly departing. Yablonsky suggests that Morgan has put the organisation back on course by putting its renovation projects on a solid footing and mustering support while also “correcting a serious imbalance of gender representation in the collection” through acquisitions.

It is notable that after Raven’s installation, the next artists in the pipeline at Dia Chelsea are women as well: the US-born, Norwegian-based artist Camille Norment, known for her sound-based pieces, and Delcy Morelos, a Colombian sculptor who works in earthen materials and is attuned to indigenous culture.

De Gunzburg credits Morgan with forging cohesive goals that paved the way for the renovation and the plans for the SoHo and Beacon renovations. “Dia didn’t have a strong director for 10 years,” she says. While Philippe Vergne, Morgan’s predecessor, who held the post from 2008 to 2014, “was a very good curator,” she says, “you have to be a visionary. And Jessica is an incredible manager.”

“It took her one, two, three years to wrap her head about what she wanted for Dia, and when she did, we were very happy with it.”

Morgan says that while the Chelsea space has a crucial role to play in presenting artists, she also hopes that it will also be “incredibly important as an informational hub” that illuminates what Dia’s other ten sites have to offer, especially the free New York locations.

“Our audience in Beacon is around 70% under the age of 30, and it’s very young people who are coming from Queens and Brooklyn and Manhattan,” she notes. “They're repeat visitors, and getting them to connect Dia Beacon with all of our other sites is important for us. It’s really wanting people to connect the dots.”

Lucy Raven, Casters X-2 + X-3, 2021 Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York