In a world where more than 200 million people pay for Netflix and 155 million are premium subscribers on Spotify, cash-strapped museums are slowly waking up to the monetary gains of online content.

While galleries of masterpieces have lain empty for months, museums have poured their energies into digital channels in a bid to stay connected with audiences confined at home. And amid the torrent of free 360-degree tours, webinars and social media challenges, a handful of institutions are testing out a new revenue-generating model: selling on-demand exhibition films, expert talks and art education classes online.

Last November, two London museums announced virtual tours of popular exhibitions that had been postponed by the first UK lockdown and then abruptly curtailed by a second wave of restrictions. The National Gallery’s half-hour film explored highlights of its survey of Artemisia Gentileschi, presented by the curator Letizia Treves—for the price of £8, or free for members (from £60 a year). The Design Museum rallied curators, musicians and designers to illuminate its show on the history of electronic music; the video tour, running until 3 May, costs £7 (free to members, from £65 a year).

The Artemisia show at London's National Gallery Photo: National Gallery

Elsewhere, the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris gave “micro-tours” of its closed Cindy Sherman retrospective for up to nine people at €4 each. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York—which is also open for physical visits—runs a range of hour-long virtual tours by appointment, costing $300 for groups of up to 40 adults and $200 for students. Online lectures explore themes in the collections of the UK’s Birmingham Museums Trust for £12.50 each, while a monthly package costs £20. And in Vienna, the Kunsthistorisches Museum is hosting live Zoom sessions, from a €3 lunchtime talk to customised private tours priced €150 to €200.

“It was a punt in a way—we thought there might be demand,” says Tim Marlow, the director and chief executive of London’s Design Museum, about the virtual tour for Electronic: from Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers. Even before the show opened in July last year—with 30% capacity to allow social distancing—£18 tickets for weekend slots were booked until the autumn. Making a documentary-style film was a way to engage audiences unable to travel to London, Marlow says, as well as a contingency against a second shutdown.

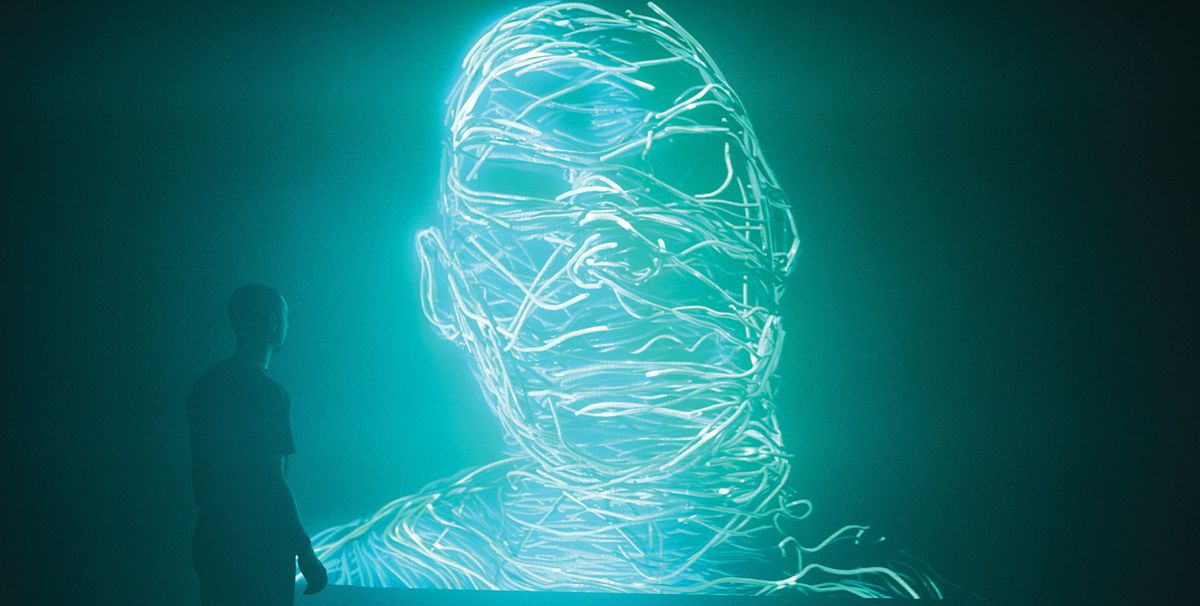

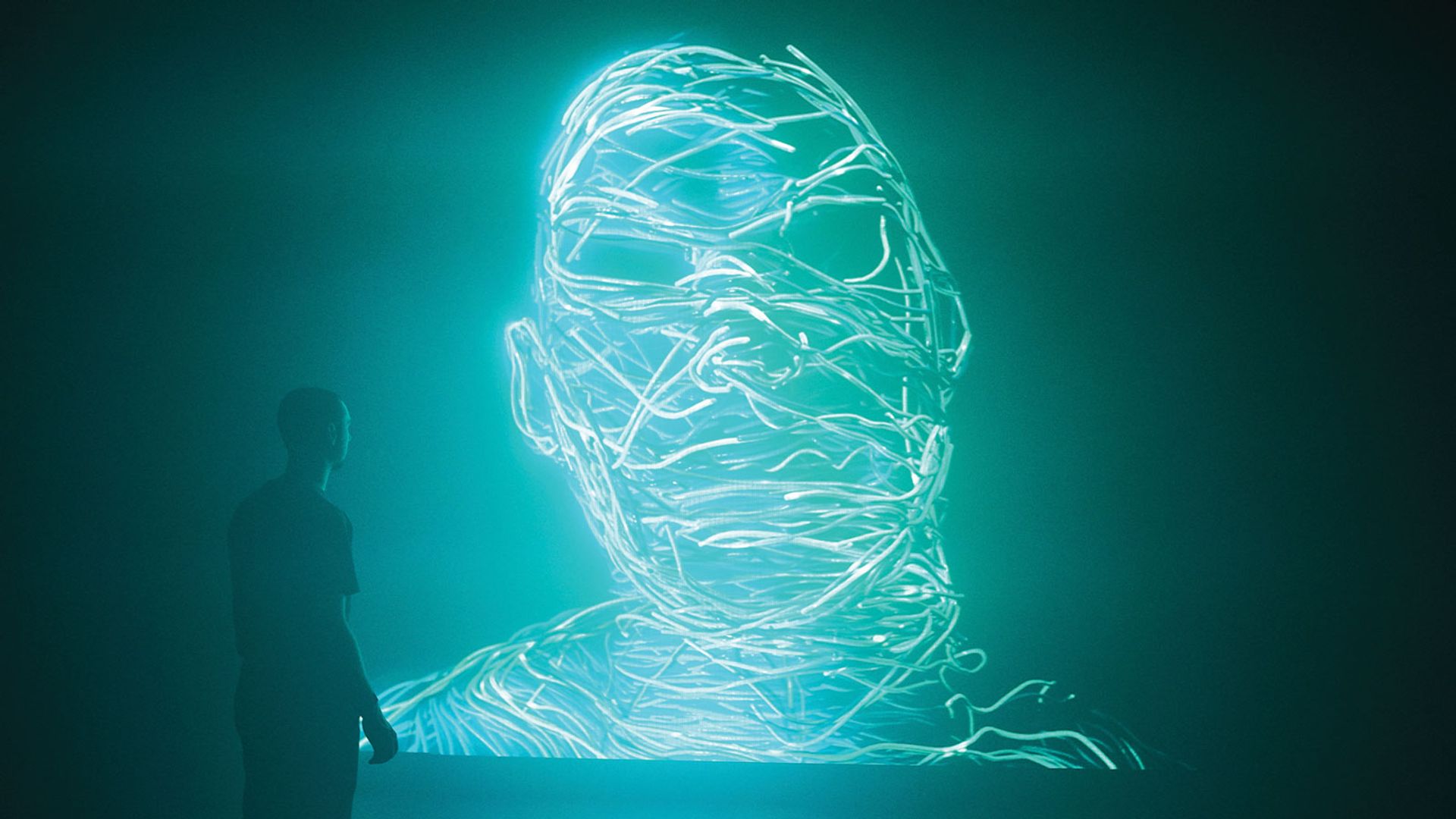

Got To Keep On (2019), an installation by The Chemical Brothers and Smith & Lyall was on show at the Design Museum Photo: Feliz Speller for the Design Museum

The National Gallery’s online Artemisia tour was also driven by the “unique circumstances” of 2020, says Chris Michaels, the director of digital, communications and technology. “Two things were happening: a remarkable year of exhibitions was heavily disrupted and there was an upsurge in digital adoption from our audiences.”

From March 2020 to January this year, the gallery saw a 1,125% leap in traffic to its webpage for new digital content. Since June, it has met the growing public interest by staging more than 200 virtual events, including educational workshops, talks and courses. The mix of free and paid offerings mimics the gallery’s public programme before the pandemic, Michaels says. So far, educational audiences and members “have been comfortable to pivot”, he adds, helped by the “mass adoption of Zoom”.

Show me the money

But how many online museum visitors are willing to pay—and can they offset the drastic loss of income from the traditional box office, café and gift shop? Even as museums reopen, tourists are not expected to return for years to come.

For now, “money can’t be a priority [for digital engagement] simply because there is no market reference,” Michaels says. The National Gallery had no revenue targets for the virtual Artemisia tour and sales are undisclosed. The figures are “pretty good” but the “most important thing is learning”, Michaels says. The more museums experiment with their own paid initiatives, “the quicker we’ll find out the format, the price, how it works”, he thinks.

Premium digital content “won’t be a big cash cow, but it will reach different audiences”Tim Marlow, Design Museum director

Premium digital content “won’t be a big cash cow, but it will reach different audiences and suggest an equivalence of the experience if you can’t visit”, Marlow says. Compared with the 50,000 who bought tickets for the Electronic show, more than 4,100 had paid to access the video tour by late February. Strikingly, most of the latter came via the Facebook Live “premiere”, which included an introductory talk. Marlow says the “sense of an event” also bolstered attendance to a £5 online talk on rave culture with the artist Jeremy Deller, which drew 1,000 viewers.

The results have encouraged plans for more revenue-generating digital activity around a forthcoming exhibition on footwear, but “it’s not about coming up with a formula”, Marlow asserts. “The model will be mixed going forwards.” A summer show on the designer Charlotte Perriand, for instance, will have a free app sponsored by Bloomberg.

Exclusive experiences

Yet rather than attempting to recreate the crowd-pulling allure of exhibitions through a computer screen, museums might do better to monetise more bespoke, interactive and expert-led experiences online.

“An exhibition is hard to translate into digital,” says Bernadine Bröcker Wieder, the founder and chief executive of Vastari, an online platform that facilitates exhibition loans between museums and private collectors. Besides their grand buildings and rich collections, Bröcker Wieder argues that museums harbour an overlooked asset: the expert interpretation at the root of exhibition-making. “Private views, expert tours—those are what people are willing to pay for,” she says.

Museums have developed “all sorts of monetisation models” for their buildings but “their entire digital ecosystem was focused around this physical experience”, observes Wouter van der Horst, the head of content and learning at the museum app Smartify. Rather than seeing digital platforms as purely a marketing tool for exhibitions, museums could use them to create meaningful and educational “online experiences” that are “worth subscribing for”, he thinks. “There is so much untapped potential.”

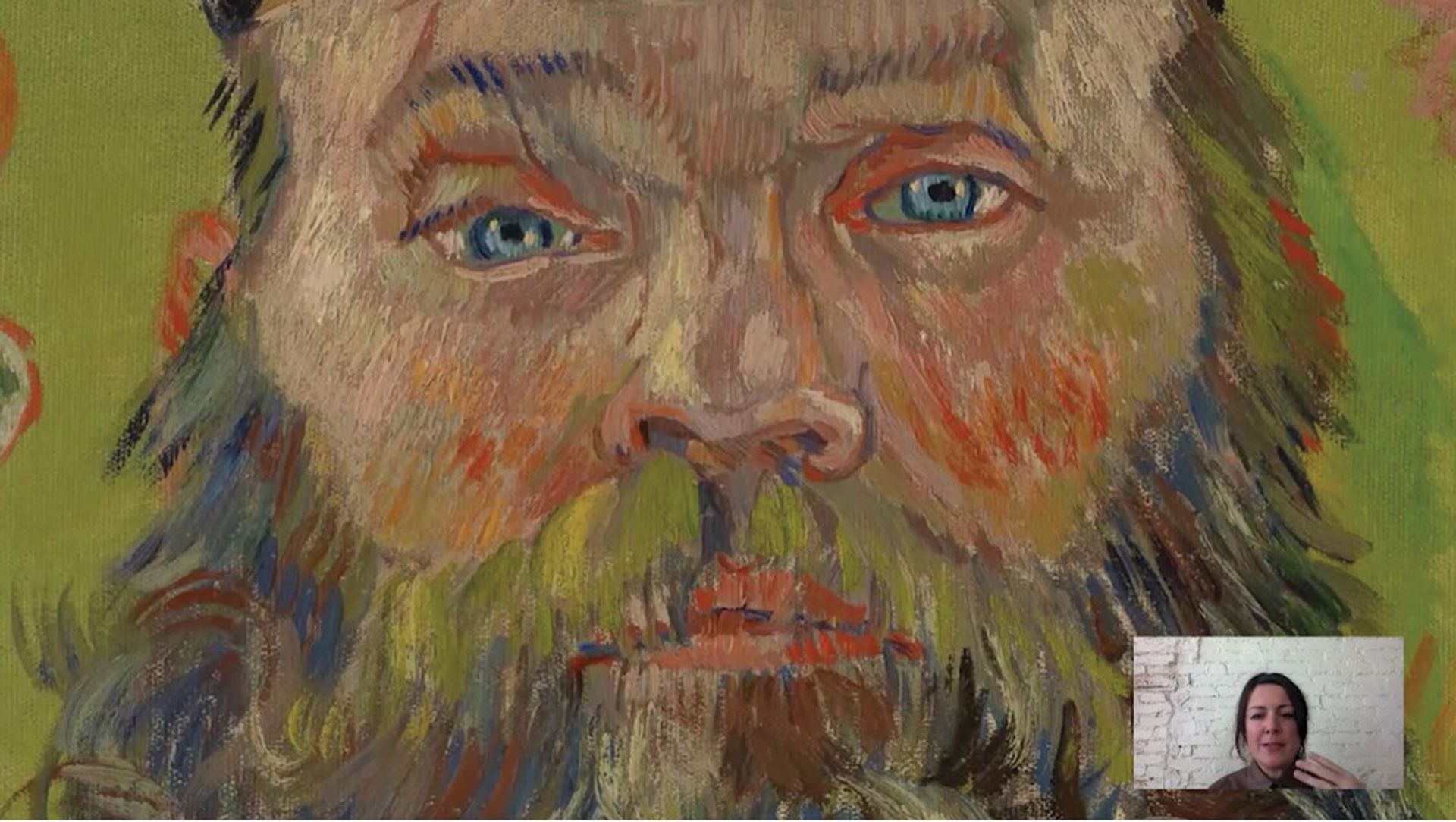

Seeing high demand during lockdown for its free educational videos such as this one on Van Gogh’s Postman, the Barnes Foundation decided to expand its offerings of paid online courses Barnes Foundation

The success of online classes at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia seems to bear these theories out. Upholding the educational mission of its founder, Albert C. Barnes, the museum switched its in-gallery adult programme to Microsoft Teams last March. Seeing high demand during lockdown for its free educational videos on YouTube, the foundation decided to expand its paid online courses, says Will Cary, the chief of business strategy and analytics. Forty-six new classes were added from April to December, catering to more than 2,800 students across the US and abroad.

“Last year has taught us that there is a market for high-quality adult education online”Will Cary, chief of business strategy and analytics at the Barnes Foundation

Thanks to Deep Zoom technology that allows educators to livestream digitised works of art down to the brushstrokes, the Barnes Foundation “tapped into the core of what we’ve done for the better part of 100 years”, Cary says. And with tuition fees of $220 for four classes, the online programme has already raised more than $600,000 in revenue, more than double that of in-gallery classes in 2019. According to a spokeswoman, this helped the foundation to achieve “a budget surplus” for 2020, despite the loss of income during 25 weeks of closure.

The museum plans to “scale up” online classes even after teaching in the galleries resumes later this year, Cary adds. “Last year has taught us that there is a market for high-quality adult education online that can provide a significant new source of earned revenue for our institution,” he says, noting that tuition fees “go directly to support free and low-cost programmes”.

As museums worldwide struggle to balance the books after a year of crisis, now may not seem an obvious time to invest in digital. The risk is that the sector will “shrink back rather than thinking about this as an opportunity to grow”, Bröcker Wieder says. “What I hope in 2021 is that museums realise, actually, there is something here we can do.”

• Read all our Visitor Figures 2020 content here