In January, the French department for marine archaeological research—known as Drassm from its French name—launched the Alfred Merlin, the newest member of its highly specialised fleet. Built in a shipyard in La Ciotat on the Côte d’Azur, the ship is a 46m-long gleaming white beauty with red and blue stripes running at a slant down its side. Ahead of testing this month and delivery in May, the vessel has been equipped with, among other things, a stern gantry that is tall enough to load a small submarine and a bridge bristling with the latest technologies called “une passerelle du futur”—a bridge of the future.

The Alfred Merlin is named after the French archaeologist who in 1907 led the world’s first underwater excavation, off the coast of Tunisia. France became the first nation to have a dedicated underwater heritage department when André Malraux, the then culture minister, created the Drassm in 1966.

Its global leadership in the field has remained unchallenged, not least because it has a lot on its plate. France’s underwater territory is the world’s second largest, with European waters accounting for a mere 5% of that: the nation’s colonial past writ large.

France’s underwater territory is the world’s second largest Photo: Teddy Seguin/DRASSM

Part of the archaeological riches discovered on the wreck of the Jeanne Elisabeth near Maguelone in the south of France Photo: Teddy Seguin/DRASSM

The Alfred Merlin’s 2021 schedule is already full, with surveys in the Mediterranean and an ongoing search off the coast of Brest for the 16th-century wrecks of the Cordelière and Henry VIII’s Regent. The Alfred Merlin will also contribute to the ongoing search for the Leusden slave ship in Suriname and French Guiana waters. Locating the site of this catastrophic 1738 sinking, in which 664 African captives drowned after the Dutch crew imprisoned them in the hold before jumping ship, is crucial as it is both a mass burial ground and a historical crime scene.

Drassm’s existing single-hull vessel, the André Malraux, was the epitome of cutting-edge shipbuilding when it was launched in 2012, and the department’s director, Michel L’Hour, says it was soon in overwhelmingly high demand. By 2015, the Alfred Merlin was in the research and development stage and had been dubbed Nessie, which stood for Novel Efficient Survey Ship Initiative, and also hinted at a certain collective incredulity. The Drassm team was pouring all of its ideals and half a century of French expertise into a dream boat they were not certain would ever surface.

Drassm’s existing single-hull vessel, the André Malraux, was the epitome of cutting-edge shipbuilding when it was launched in 2012 Photo: Teddy Seguin/DRASSM

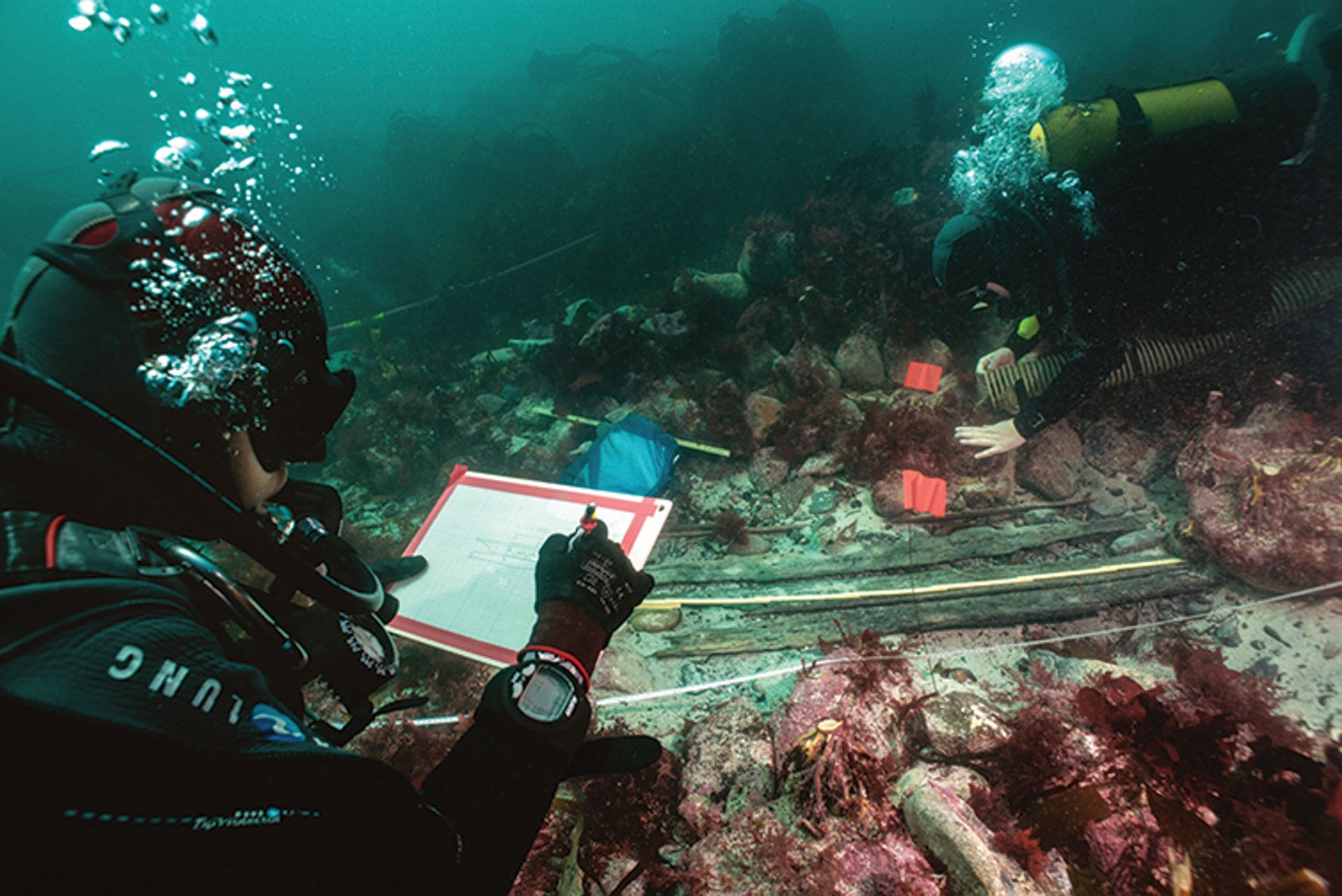

The André Malraux ship during the excavation of the wreck of the Indian, an English ship that sank in December 1817 off the coast of Kerlouan in northwestern France Photo: Teddy Seguin/DRASSM

L’Hour says the Alfred Merlin sits “just this side of Jules Verne territory”, midway between science- fiction and history. It is one of the largest ships ever to be made entirely of composite materials (and will serve as a floating laboratory for studying these over time). From an archaeological point of view, it is also a game changer.

Where the André Malraux cannot cross the Atlantic, the Alfred Merlin will easily make it from Brittany to, for example, Saint Pierre and Miquelon off the coast of Newfoundland, or—with a pit stop in the Canary Islands—to the French West Indies. It has space for 28 people to live and work for ten days, air and nitrox gas capacity for up to 20 divers, high-end electronic detection and measurement systems, the latest in computers and, crucially, robots.

Over the past decade, in concert with roboticists at Stanford and Montpellier universities, Drassm has developed a unique underwater “crew”. There is the humanoid Ocean One (more avatar than machine, it is piloted by an archaeologist on deck via haptic interfaces so “if Ocean One breaks something,” L’Hour says, “that’s on you”); a couple of revolutionary robotic hands, capable of the delicate, precise manipulation that a dig requires; and a fleet of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), of which one, Hilarion, is a videographer able to relay footage to its surface operator in real time. Arthur, meanwhile, is a new lightweight robot with a diving range of up to 2,500m—two and a half times deeper than what had previously been possible.

The Ocean One underwater robot is piloted by an archaeologist on deck via haptic interfaces Photo: Frédéric Osada/Teddy Seguin/DRASSM

The Capo Sagro 3 wreck (2nd century BC) off the eastern coast of Corsica in the Mediterranean, was surveyed by French archaeologists at a depth of 1,500 feet Photo: Frédéric Osada/DRASSM