A district judge recently ruled that the Vermont Law School in South Royalton can erect a wall to hide a mural many of its students have criticised as offensive, without violating a 1990 federal law that protects works of art from destruction or modification without the artist’s consent.

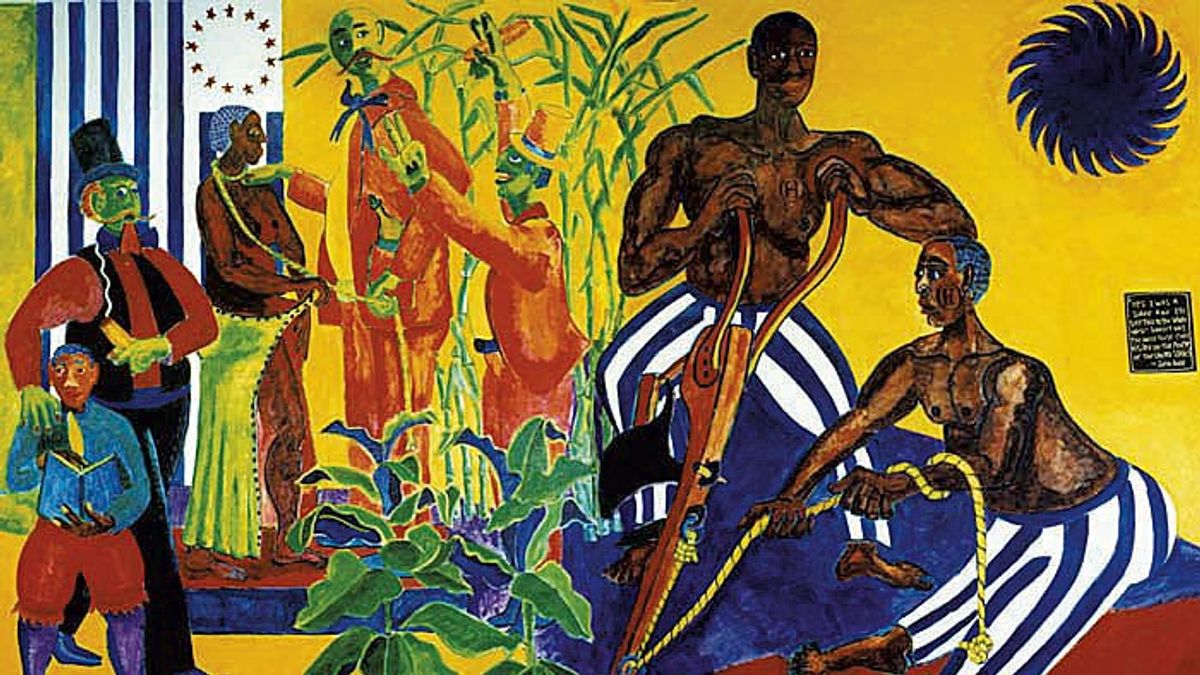

The Underground Railroad, Vermont and the Fugitive Slave, which was painted in acrylic on two panels of sheet rock by the Canadian artist Samuel Kerson in 1993, depicts scenes of escaping slaves and white Vermonters protecting them. Black students at the school described the cartoonish images of half-naked Africans as “unsettling” and “eerily similar to Sambos, and other anti-Black coon caricatures”, while the mural’s idealised presentation of white abolitionists helping them—and decision to have the slave owners in the mural painted with ghoulish green skin instead—“perpetuates white supremacy, superiority, and the white savior complex”.

The student’s complaints led the law school’s dean Thomas McHenry to issue a statement that “the depictions of the African-Americans on the mural are offensive to many in our community and, upon reflection and consultation, we have determined that the mural is not consistent with our School’s commitment to fairness, inclusion, diversity, and social justice.” Last July, the law school announced that it planned to paint over the murals.

But when the artist learned about the decision, he informed the school that his work was protected by federal law: the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act, an amendment to US Copyright Law that protects works of “recognised stature” from “any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification”. In August, the law school sent Kerson notice that he had 90 days to remove the murals and, failing that, the school would remove or cover them. Kerson, however, concluded that he could not remove the painted image from the sheetrock affixed to the building without destroying the mural, and filed a lawsuit against the school in early December.

The law school’s solution was to sidestep VARA, opting not to destroy or even touch the murals but to put up a wall in front of them. Kerson tried to put a stop to those plans but lost his case, with US District Court Judge Geoffrey W. Crawford writing in his 12 March decision that “in the limited law available concerning the VARA, an owner’s decision to conceal a work does not constitute modification or mutilation”. The judge added that covering the murals without damaging them is comparable to an art museum removing a painting and putting it into storage.

Kerson, responding to questions by email, calls Judge Crawford’s ruling an error, allowing his mural to be “entombed”. He adds that “as part of the social history of Vermont, the mural might be taught about rather than feared”. The Vermont Law School did not respond to The Art Newspaper’s requests for comment on either the controversy or the court ruling, but Justin Barnard, a lawyer for the school told the Valley News: “It is not Vermont Law School’s plan to make it available for viewing again.”

Opinions on the ruling are divided among those in the legal community. Rebecca Tushnet, a professor of first amendment law at Harvard Law School, says that Judge Crawford’s decision had precedent in another ruling involving an installation at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, in which “the court ruled that covering a work with a tarp wouldn't violate VARA’s right against distortion.” She added that “I find it hard to see how simply walling off the art could violate VARA.”

On the other hand, retired Harvard Law School professor Laurence Tribe, notes that from “the artist’s perspective and that of all who might want to view the mural, walling off the work with solid brick is the functional equivalent of destroying it”. He adds that “the law school’s ‘solution’ does seem likely to have exploited a loophole in the federal statute.”

Tribe describes Vermont Law School’s action as an example of “cancel culture,” while Tushnet says that “it’s natural to rethink those things as our collective values change”. She adds: “Sometimes that might mean contextualising existing art, but sometimes it could just mean replacing it.”