“When we say, ‘This is a Botticelli,’ what do we mean? If the phrase implies that the master conceived the work and executed it without assistance, few paintings would qualify,” writes Jonathan Nelson, teaching professor at Syracuse University, Florence, in his 2009 article, “‘Botticelli’ or ‘Filippino’? How to Define Authorship in a Renaissance Workshop”.

“With the exception of some very small works,” Nelson notes, “virtually all paintings by major Renaissance artists were made with varying degrees of workshop assistance.”

This is not what the trade in Old Masters wants to hear. For centuries, it has relied on connoisseurial expertise to judge to what extent a painting has been executed by a famous artist or by unknown assistants. Financial value depends on whether a painting is deemed “autograph” or not.

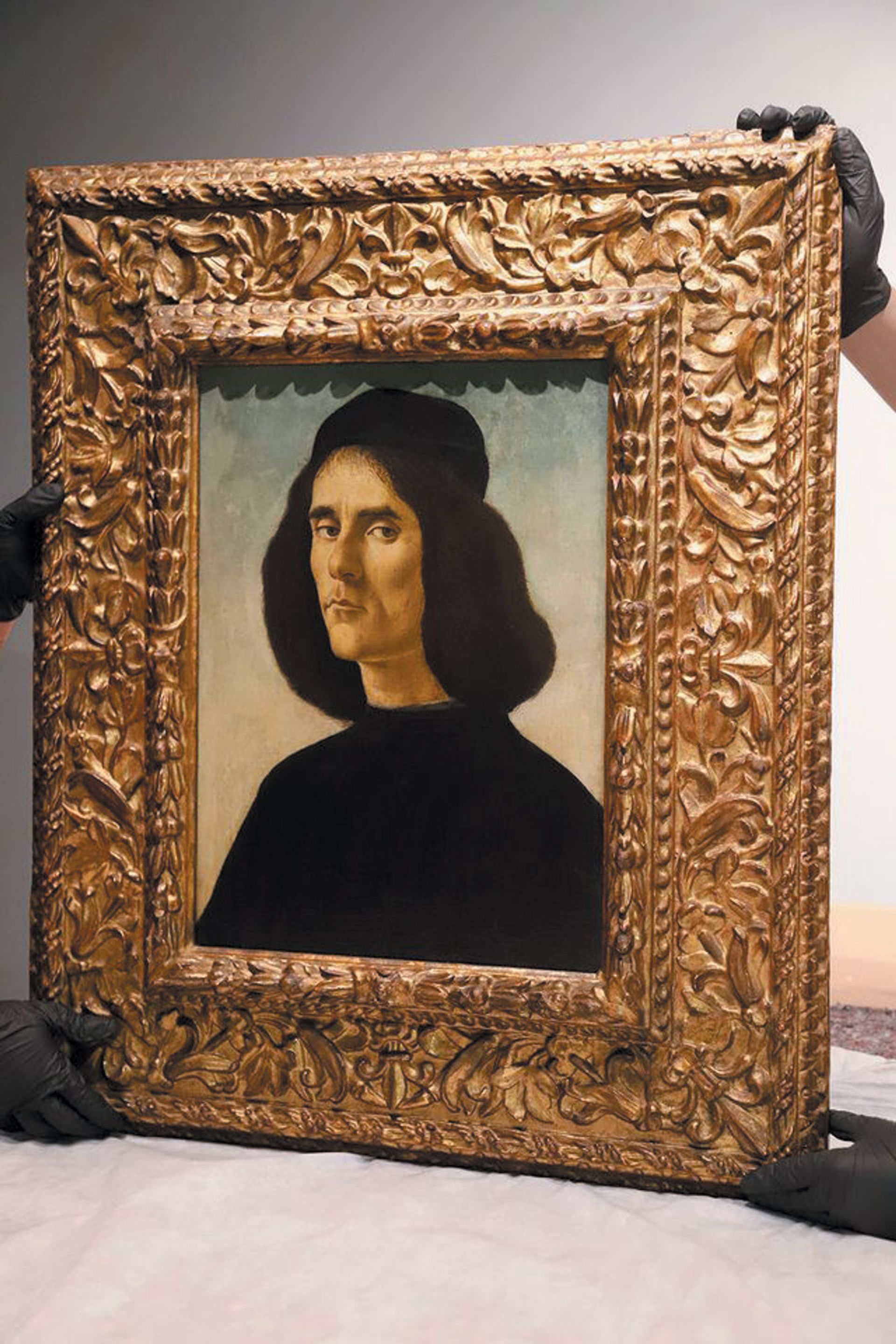

Sandro Botticelli portrait of the Greek-born poet and soldier Michele Marullo Tarcaniota Courtesy of Trinity Fine Art. Photo: Mark Dalton

In January, Sandro Botticelli’s Young Man Holding a Roundel (around 1470-80) sold for $92.2m (with fees) at Sotheby’s in New York—the highest price ever achieved for an Old Master at a Sotheby’s auction. It was also way above the $30m asked by Trinity Fine Art in 2019 for a portrait of the Humanist poet, Michele Marullo Tarcaniota, billed, a little prematurely, as the last fully accepted Botticelli painting left in private hands.

But Young Man Holding a Roundel has only recently acquired “autograph” status. Ronald Lightbown’s 1978 catalogue raisonné of Botticelli’s paintings included it among works “attributed to Botticelli or his school”. In 1982, when the portrait last appeared at auction, it was declared by the then-influential art critic Brian Sewell to be by Francesco Botticini, an attribution favoured by the eminent Renaissance scholar, Everett Fahy. As a result, it sold at Christie’s for just £810,000.

The transformation from catalogue addendum to what Sotheby’s described as one of Botticelli’s “finest and most significant works” has been remarkable. This kind of attributional upgrade has become the main way collectors, dealers and auction houses can lift the value of a centuries-old picture. But while art historians currently do seem to agree that Sotheby’s portrait is an “autograph” Botticelli, scholars increasingly view this as an anachronistic form of assessment.

“The concept of authorship in the Renaissance is very different from how we are inclined to think now,” says Ana Debenedetti, a curator at the Victoria & Albert museum. “Any ‘Botticelli’ implies a workshop contribution.”

Debenedetti is the co-curator of an exhibition (scheduled to open in September) at Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris, which will show the importance of Botticelli’s studio as a “laboratory of ideas and training centre”, characteristic of the Italian Renaissance.

“He has a very strong style, ranging from his highly recognisable prototypes through his many replicas. He created his own brand,” says Debenedetti, who estimates that Botticelli had at least five assistants at any one time.

“Part of the problem is terminology. How do we refer to pictures made by more than one person?” says Michelle O’Malley, the professor of Renaissance Art History at the Warburg Institute in London, who has made a special study of Botticelli’s workshop-produced religious paintings.

O’Malley points out that auction houses’ determination to catalogue Renaissance paintings as “by” an individual artist dates back to the era when Sotheby’s and Christie were founded. “In the late 18th century, English and Italian collectors began to look again at the Italian Renaissance and tried to match up paintings with names in Vasari [Lives of the Artists, 1550/68],” O’Malley says. “At that time, painters were working alone, in individual studios or even garrets. Probably because of this, the people who collected Renaissance works were no longer speaking in terms of corporate production, but of the heroic, genius artist.”

Adoration of the Christ Child (around 1510) by “Lorenzo di Credi and Workshop”

No room for dissent

Romantic notions of the artist as heroic genius still underpin the huge price-tags for trophy Old Masters. The merest hint of collaboration, let alone an alternative attribution, can result in a massive reduction in value, or auction failure. Adoration of the Christ Child (around 1510) by “Lorenzo di Credi and Workshop” from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, estimated at $600,000 to $800,000, proved the point when it found no takers at Sotheby’s in January.

Little wonder, then, that in 2017, prior to the $450.3m (with fees) sale of the Salvator Mundi, Christie’s catalogue reassured would-be bidders that there was an “unusually uniform scholarly consensus that the painting is an autograph work by Leonardo.” A preparatory drapery study exhibited as “Leonardo da Vinci and Workshop” in the National Gallery’s 2011-12 Leonardo exhibition was illustrated in Christie’s catalogue as “Leonardo da Vinci”.

Auction houses and their sellers are today understandably nervous that attributional doubts will soften demand for a big-ticket Old Master. Dissenting voices are not encouraged.

In 2019, the French auctioneers Marc Labarbe and Eric Turquin were commendably open to debate before their scheduled auction in Toulouse of a painting of Judith and Holofernes they believed to be a rediscovered masterwork by Caravaggio. Three years earlier, the painting had been the subject of the conference, “A Question of Attribution” at the Brera museum in Milan. Afterwards, Keith Christiansen, the chair of European paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, wrote a report, saying that while experts agreed the picture had “undeniable quality”, it contained too many crude details to be regarded as an autograph Caravaggio.

Although estimated to sell for at least €100m, the picture in the end sold privately for an undisclosed price nearer the reserve of €30m.

“There’s a deep-seated desire to see the individual operating”Jonathan Nelson, professor

Meanwhile, auction houses continue to sell earlier Italian paintings that have been matched up with names in Vasari’s Lives. This month, for instance, Sotheby’s will offer a portrait of a young man catalogued as an autograph quality work from around 1470 by the Florentine painter, Piero del Pollaiuolo, the brother of the goldsmith Antonio del Pollaiuolo, who, according to Vasari, “identified himself completely with Piero, and in conjunction they produced a quantity of pictures”.

Estimated at £4m to £6m, Sotheby’s painting, like the Botticelli, had formerly been owned by the English scientist Thomas Merton. This portrait has also been subject to a certain amount of attributional to and fro.

Subjectivity of connoisseurship

Back in 1985, it was sold at Christie’s as a portrait by the less-lauded Cosimo Rosselli for £91,800. In 2005, the painting was reattributed to Piero del Pollaiuolo in Alison Wright’s The Pollaiuolo Brothers: the Arts of Florence and Rome. However, Laurence Kanter, the chief curator of the Yale University Art Gallery, whom Sotheby’s cited as an admirer of its ex-Merton Botticelli, tells The Art Newspaper: “The painting has nothing to do with Piero Pollaiuolo. I believe the old attribution to Cosimo Rosselli, despite its apparent unpopularity, was correct.”

Sotheby’s says in response: “Although an alternative attribution to Cosimo Rosselli was subsequently proposed, the view that the painting is by Piero del Pollaiuolo is now supported by the overwhelming majority of leading scholars in this field, including Alison Wright, Keith Christiansen, Antonio Natali, Angelo Tartuferi, Aldo Galli and the late Everett Fahy.”

Ultimately, such connoisseurial attributions remain subjective. Opinion and information can change. Would the rarefied world of Old Masters benefit from being a bit more relaxed about this situation?

Although Judith and Holofernes has been attributed to Caravaggio, its authorship has been hotly contested and in 2019 it was sold privately, well below its auction estimate Photo: Jonathan Brady; PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo

“There’s a deep-seated desire to see the individual operating,” Nelson says. “At times we have to let go.” Nelson is relaxed about Sotheby’s cataloguing Young Man Holding a Roundel (a painting he knows well) as an “autograph” Botticelli, even though he can imagine the workshop being involved in details such as a ledge or even an area of drapery. “Most Renaissance patrons didn’t have a clear sense of individual style,” Nelson adds.

This is exactly how today’s patrons feel about most of the art produced by successful living artists—such as Damien Hirst, Takashi Murakami and Jeff Koons—most of whom run extensive studio operations. They are buying an instantly recognisable brand, rather than a unique expression of individual genius.

“There is a very clear through line from the studio practices of Old Masters to how many contemporary artist studios work today. And attribution is never considered as anything other than by the artist,” says Christopher Apostle, Sotheby’s head of Old Master paintings in New York. Nonetheless, Apostle sees no reason to update the long-standing catalogue terms for Old Masters, in which the unmodified name Giovanni Bellini, or Sandro Botticelli, denotes that in Sotheby’s “best judgment” the work is “by” the artist.

The slick pre-auction marketing for the Botticelli said it was a masterpiece that would “establish art market history”. In the end, it attracted just two bids. But Sotheby’s did make history by partnering with a jewellery brand that used the auction itself as a marketing platform. The live stream of the sale was preceded by a Bulgari advertisement, and Sotheby’s staff took bids wearing Bulgari watches and jewellery. Auctioneer Oliver Barker, pausing between bids, enthused about “the fabulous Bulgari necklace” one of his colleagues was wearing.

Traditionalists were predictably appalled by the Bulgarisation of something as venerable as a Sotheby’s Old Masters auction. But how would a wealthy 15th-century Florentine have felt about this fusion of brand-name art and brand-name luxury?

Maybe Botticelli and Bulgari have more in common than today’s art world cares to admit.