Sotheby’s sale this month of an arresting Botticelli portrait, owned by the late real estate billionaire Sheldon Solow, has been heavily publicised.

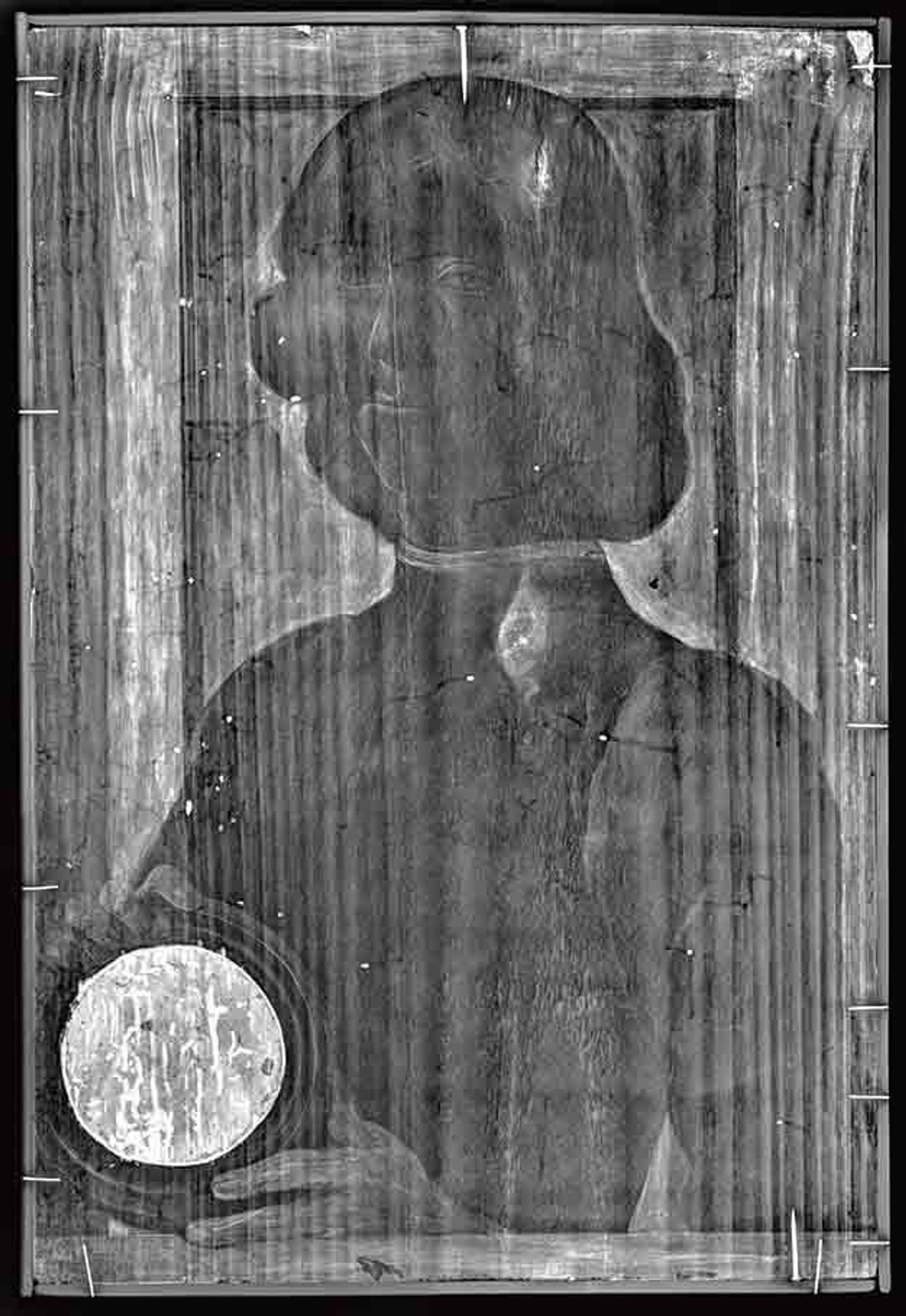

Yet, while Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel (around 1480) is accompanied by the obligatory paraphernalia of X-ray and infra-red images, its many mysteries continue to confound trade and scholars alike.

And the estimate, in excess of $80m, has no precedent: works fully attributed to Botticelli rarely come up and the auction record for a painting by the artist is just $10.4m, set in 2013 by the “Rockefeller Madonna” (or Madonna and Child with Young Saint John the Baptist). In December, Sotheby’s in London sold a (guaranteed) oil on panel of Christ on the Cross attributed to Botticelli for only £1m (with fees, est £800,000-£1.2m), selling to an online bidder based in Asia.

There is, as a Sotheby’s spokesman puts it, a considerable “scale in estimates”.

The attribution

The present portrait, in tempera on poplar panel, is both the quintessential visual expression of 15th-century Florentine culture and profoundly modern “in its high degree of abstraction”, as the sale catalogue puts it. It was first auctioned as a mature work by the great Florentine Renaissance master in 1982, although the attribution—dating back to 1941, when it first entered the physicist Thomas Merton’s celebrated collection—was only definitively endorsed in 1987 by Richard Stapleford.

"It is surprising how often scholars have questioned its attribution to the master.”David Alan Brown, author

No one doubts the striking beauty and quality of the portrait, yet there are those who still question whether it should be ascribed to Botticelli or to his school. When it was exhibited at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in 2001-02, David Alan Brown wrote in the catalogue entry: “Given the superb quality and inventiveness of the portrait, it is surprising how often scholars have questioned its attribution to the master.”

Among scholars who regarded it with caution were Frank Zöllner, who, in his 2005 catalogue of Botticelli’s works placed it in the group of “contested and uncertain attributions”, partly due to a lack of provenance. Sotheby’s can now trace this back to 1850 Wales, but no further. New technical examinations have also contributed to Sotheby’s confident attribution and to a more confident assessment by Zöllner.

The roundel, which the young man holds, contains a 14th-century fragment; the X-ray (below) shows clearly that this is a “foreign body” COURTESY OF SOTHEBY’S

The Renaissance expert Laurence Kanter was recently invited to view the portrait by Sotheby’s, New York. For Kanter, its chequered critical history is “totally immaterial”, while the latest X-rays and infra-reds don’t tell him anything that he can’t see with his own eyes: an “enthralling” Botticelli.

When it was last sold by Christie’s in 1982, the portrait achieved £810,000. The Getty hoped to buy it but stepped aside, according to its chief curator Burton Fredericksen, after the authority Everett Fahy, then the director of New York’s Frick Collection, declared it to be by Francesco Botticini (a follower of Botticelli; Fahy apparently later changed his mind). It now comes to auction naked, with no guarantee at Solow’s behest—unusual for a high-value lot in these unsettled times. In marked contrast to its exceptional condition (no doubt due to its long hibernation in Wales), the simplicity of its window casement setting, and the clarity of its line and palette, the picture is shrouded in layers of mystery that only add to its allure.

The sitter

Various candidates have been proposed as the owner of those unflinching hazel eyes (which perhaps lack the lustre that Botticelli usually imbues the eyes of his subjects with). A. Scharf, in his 1950 catalogue of Merton’s collection, suggested the second cousin of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Giovanni di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici. This is considered plausible by some, as Botticelli did work for this branch of the Medici family, but cannot be proven. The picture was last auctioned by Christie’s in 1982 as “Portrait of Giovanni di Pierfrancesco de’Medici” and chosen as the poster boy for the Royal Academy’s 1960 exhibition of Italian art in Britain.

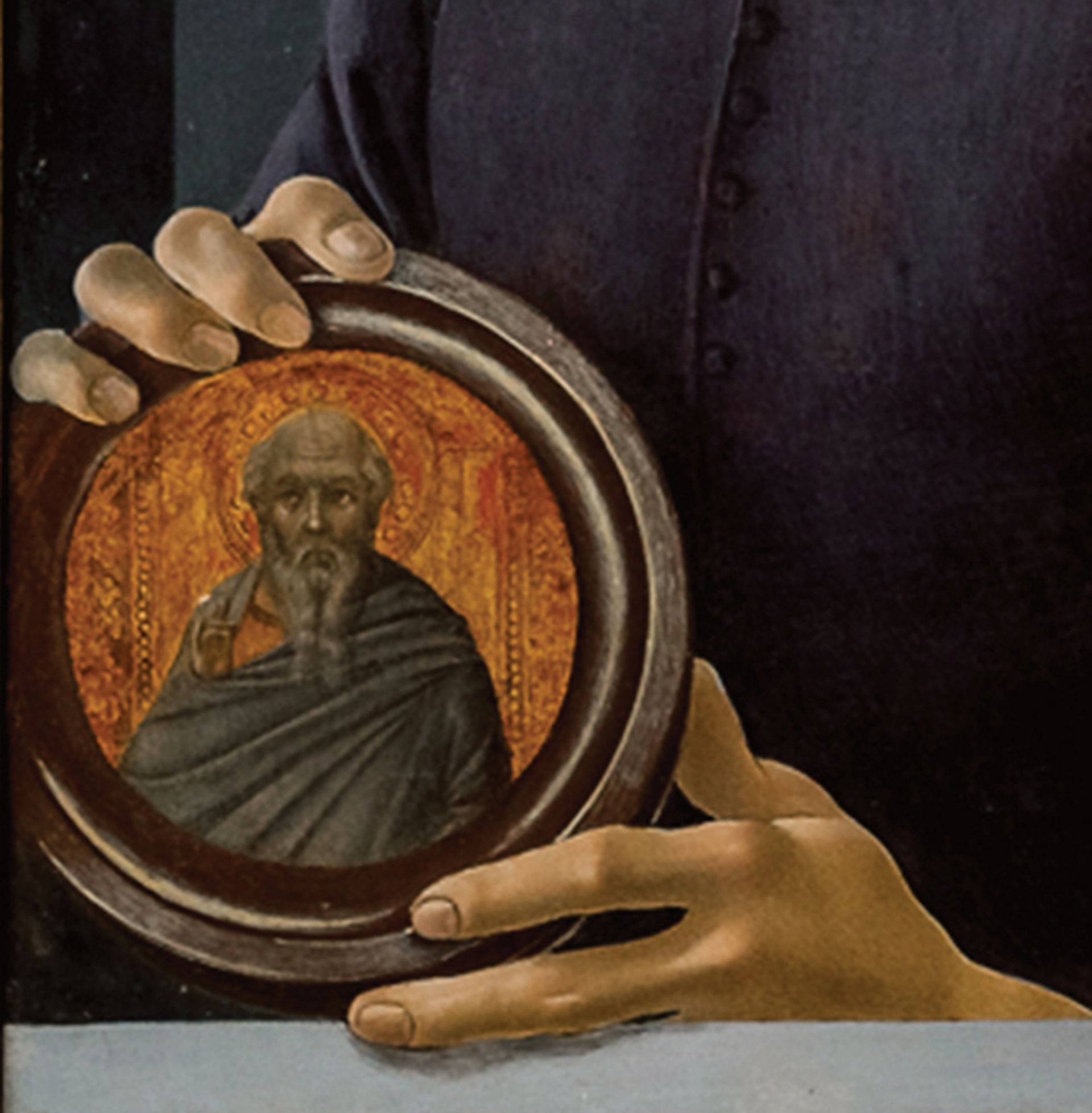

The roundel is by the 14th-century Sienese artist Bartolomeo Bulgarini

The roundel

The youth’s handsome, unblemished features contrast markedly with the hoary bearded saint (hand raised in blessing), who gazes abstractedly from within a framed roundel that the sitter holds in his elegant hands. The roundel is tilted slightly towards us, resting on an illusionistic parapet, which the youth’s fingers overlap, spilling into our space. The panel is an actual fragment of a 14th-century altarpiece; 15th-century antique dealers apparently had no qualms in chopping them up. The author of this fragment has been identified as the Sienese painter Bartolomeo Bulgarini. But why would Botticelli have incorporated Bulgarini’s panel into his portrait?

There is a precedent for a portrait of this type in Botticelli’s own work: Young Man Holding a Medal of Cosimo de’Medici (now in the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), dating from the mid-1470s. Here, another beautiful young man also holds a medallion up to the viewer, this time containing an actual gilt gesso cast of a medal of Cosimo de’ Medici (Lorenzo’s father). This may identify the sitter as a Medici partisan, while ingeniously combining two- and three-dimensional mediums (Botticelli trained as a goldsmith) in one image.

Some have argued that the Bulgarini addition may be similarly integral to the concept of this portrait. Perhaps the venerable saint is the name saint of the youth (the fragment may be of St Peter or St John), and there is a similar play on stylistic mediums—the tooled punch gold ground of the one, the airy painted sky of the other. Others have suggested that it replaced a damaged stucco relief (Roberto Longhi), and that the addition is modern (Keith Christiansen). Brown conjectures that the portrait may have originally had a circular mirror inserted into the painted frame, perhaps to reflect an image of the youth’s betrothed, in keeping with the aristocratic ideals of courtly love that dominated Florentine culture at the time. Kanter believes it could be original to the picture, although there is no way to be certain. He argues that the modern dismantling of such altarpieces usually ends up with several pieces surviving. But this is the only known single fragment.

Who commissioned it?

The dating of the portrait on stylistic grounds to around 1481 to 1485—when Botticelli produced his Sistine Chapel frescoes in Rome and mythological compositions like The Birth of Venus—sheds little light on who might have commissioned it. All we know is that the unusual aspects of this portrait, with its inventive illusionism, belong to a convention of portraiture that was clearly expensive and exclusively the preserve of the upper classes.

The one real certainty is that whoever is fortunate enough to acquire the picture will have the chance to come up with some absorbing theories of their own.

Sandro Botticelli’s Young Man Holding a Roundel, Sotheby’s, New York, 28 January, estimate in excess of $80m