Past Present Future: the title of Mary Heilmann’s exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in Zurich, which launches online on 6 February due to pandemic restrictions, reflects the fact that this is not an ordinary gallery show. Rather than revealing a body of new work, the exhibition brings together diverse works—paintings, ceramics, furniture and a slideshow—made across six decades, closer to a museum survey. But it reflects a preoccupation for the 81-year-old San Franciscan with seeing her work as a continuum. “It's an idea that’s in my head all the time: no linear time. It's all a chunk,” she says. “And especially now, during the lockdown, where I'm hiding out in my studio in the country and I'm not going very many places. I obsess about all these thoughts about the whole last time of my life.”

The show’s earliest works are from the 1970s, when Heilmann had begun to make an impact after a struggle to define her practice at two University of California campuses: Berkeley and Davis. She was caught between her impulse to make radical work—she met with artists like Bruce Nauman during her studies—and the discipline she had then chosen: ceramic sculpture. “I went up to Davis to meet William Wiley because I was having a hard time at Berkeley, because I was trying to do edgy, radical art—I was inspired by John McLaughlin, Eva Hesse, Robert Smithson, and that kind of stuff. And [at Berkeley] they were still traditional New York School sculptors.” She admits that she had “a big attitude, too”.

Mary Heilmann, Our Lady of the Flowers (1989) © Mary Heilmann. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth and 303 Gallery, New York

Her fierceness was often necessary in a male-dominated art world, especially the one in New York gathered around the legendary bar Max’s Kansas City. Antagonism was “the style for women artists, because you were sort of the enemy or the underdog”, she says. And it was also combative. “I was kind of prejudiced against the women, too,” she admits, “because I wanted to be with all the guys. Just me and Eva Hesse and two or three others… It wasn’t about seducing them, it was being at war with them or competitive with them. That was the attitude and that's deeply psychological. And that faded away, as time went along.”

Taught by David Hockney

Heilmann had moved to the East Coast in 1968 and also made the bold—and deeply unfashionable—move to painting, a medium then despised by many of the emergent artists of the New York scene, like Robert Smithson. “I started painting because I couldn't get any attention for the sculpture,” she says. She recalls the dismissal of this new direction, and the artist who most inspired her to take painting up, among her peers. “I remember sitting in Max’s, as was Smithson, who I spent time with, and I was a huge fan. When I was at Berkeley, David Hockney came over, and none of the painters would take David's class because—my theory is, I never talked to anybody about it—they were very conservative in their work. And David was amazing… And so when I was at the Max’s, I said to Smithson: ‘Oh, my teacher was David Hockney.’ And that started a whole fight. And he said: ‘I can't believe we’re even talking about him.’”

Other than in its high colour, Heilmann’s work has little in common with Hockney’s. From the start, she made essentially abstract paintings which nonetheless evoked aspects of the real world. Then, as now, they possessed a directness and vibrancy that suggested an apparent ease in Heilmann’s making of them. “That sort of off-the-grid casual attitude toward doing the work, like a sort of Asian Wabi-sabi, is a big part of my work ethic and style and philosophy—and my lifestyle, the way I live,” she says. “I had to figure out how to do it for a long time. That's part of my background in thinking about work. One of my main teachers was Peter Voulkos, teaching ceramics, and we came up in the post-beatnik, early hippie era. And we were all rough-edge hippies, so doing things in a rough, rude way, was something that he really inspired in me.”

Mary Heilmann, Clubchair 59 (2008) © Mary Heilmann. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth and 303 Gallery, New York

Nail polish and lipstick

A key factor in her work was her engagement with popular culture and other media, conflicting with prevailing tendencies in abstraction, which aimed for loftier, meta-physical ideals. Two paintings were inspired by adverts for the 1950s Revlon lipstick and nail polish Fire and Ice, for instance. “Fashion was huge for me when I was coming up. I was always getting dressed up all special, which is very much about creativity and art, also. And then music culture and dance and film.”

A group of pink-and-black paintings made in 1978 and 1979 were influenced by the punk and new wave scene in New York at the time and drew their titles from music she was listening to in the studio. “One of the main ones was Save the Last Dance for Me, which was derived from this rhythm-and-blues song by The Temptations," she says. But the works were poorly received. "And my dealer at the time came over a couple of years later and told me they'd like me to leave the gallery, in a very nice, polite way.” But, she says: “I made it to be provocative because it was minimal. And pink was a really bad colour to use, to foreground that way. It was provocative and seductive at the same time.”

Film and video also influence her. She is now “obsessed” with the way that movies “are getting made in this really provocative, non-linear way, edited and cut all over the place and inspired by artificial intelligence, being able to jump linear ideas all over the place—which is totally influencing the world, and I think in a helpful way.”

A moving image work—Heilmann’s ongoing slideshow Her Life—is part of the Zurich exhibition. It derives from the lecture using two projectors and a cassette sound-track (later a PowerPoint presentation), which made her “very popular as a visiting artist” to students who were “so bored” with conventional lectures at art schools, she says. The photographs in Her Life led to her artist book The All Night Movie, which she has toyed with making into an actual film. “I wanted to edit it in a very clever, complicated way, which could happen,” she says, “but it’s a long shot.”

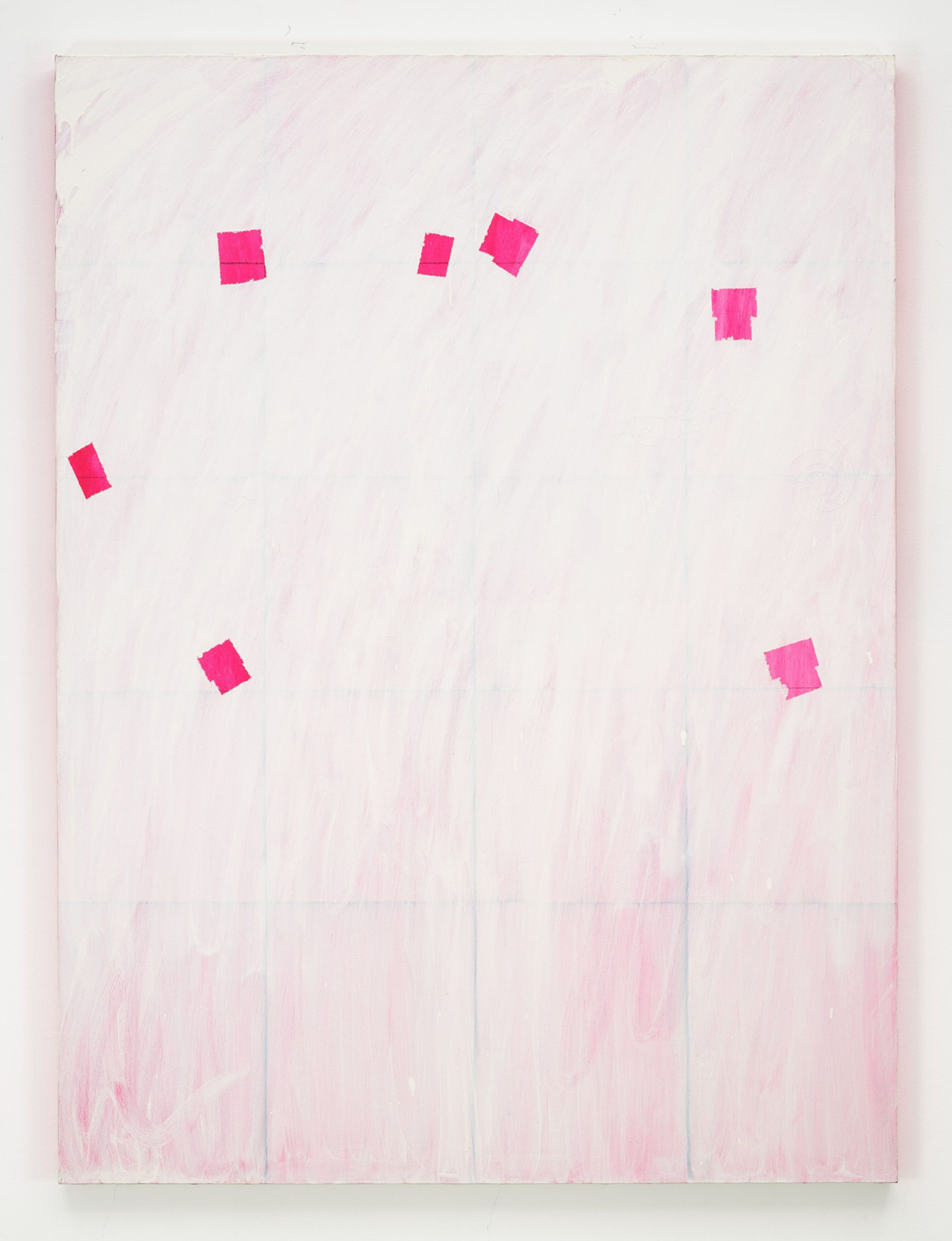

Mary Heilmann, Montauk (2020) © Mary Heilmann. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth and 303 Gallery, New York

For now, Heilmann is happy making paintings in her studio in Bridgehampton on Long Island, where she has spent more time than ever during the pandemic. It has been the inspiration for a series of pictures of the sea. “The energy of the ocean is totally here. And I do a lot of wave paintings, which will be in the show in Switzerland,” she says. “The ocean is a big part of the reason I live here. I look at it all the time.” It returns her, of course, to her native West Coast, and the beach culture there. “I never was a surfer. But I was part of that world. I went to Santa Barbara, which was a surfing school. So I call it a spectator sport, for me. And I’m really interested in the geometry of waves and the sound, the colour.” Heilmann’s waves have a freshness, a sense of deep pleasure and also a timelessness, as if Heilmann could have painted them at any point in the decades she has been coming to Bridgehampton—past, present, future, indeed.

• Mary Heilmann: Past Present Future, Hauser & Wirth Zürich, launches online on 6 February 2021