Facing challenges from a federal planning authority and advocacy groups, the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC is under pressure to revamp or justify elements of a significant redesign of its sunken sculpture garden.

The original Japanese Zen-inflected garden, which spans 1.5 acres next to the National Mall, was completed in 1974 by the architect Gordon Bunshaft as a complement to the museum’s distinctive Modernist drum-shaped concrete and granite building. The garden’s Brutalist gravel walkways and lack of shade made it inhospitable to visitors during Washington’s hot summers, however, prompting the Hirshhorn to enlist the landscape architect Lester Collins three years later to add trees, plant beds and other vegetation in a choreographic procession as well as introduce ramps for wheelchair accessibility. That renovation, which crucially retained Bunshaft’s central reflecting rectangular pool in the garden, was completed in 1981.

Since then the garden’s infrastructure has deteriorated, with cracks appearing in its walls and poor stormwater drainage leading to flooding. Noting that the garden and its 30-plus outdoor sculptures currently draw only 150,000 visitors a year, versus one million for the museum and 30 million for the adjacent National Mall, the Hirshhorn proposes to add more sculptures and make the space more welcoming and better suited for contemporary art installations and art events.

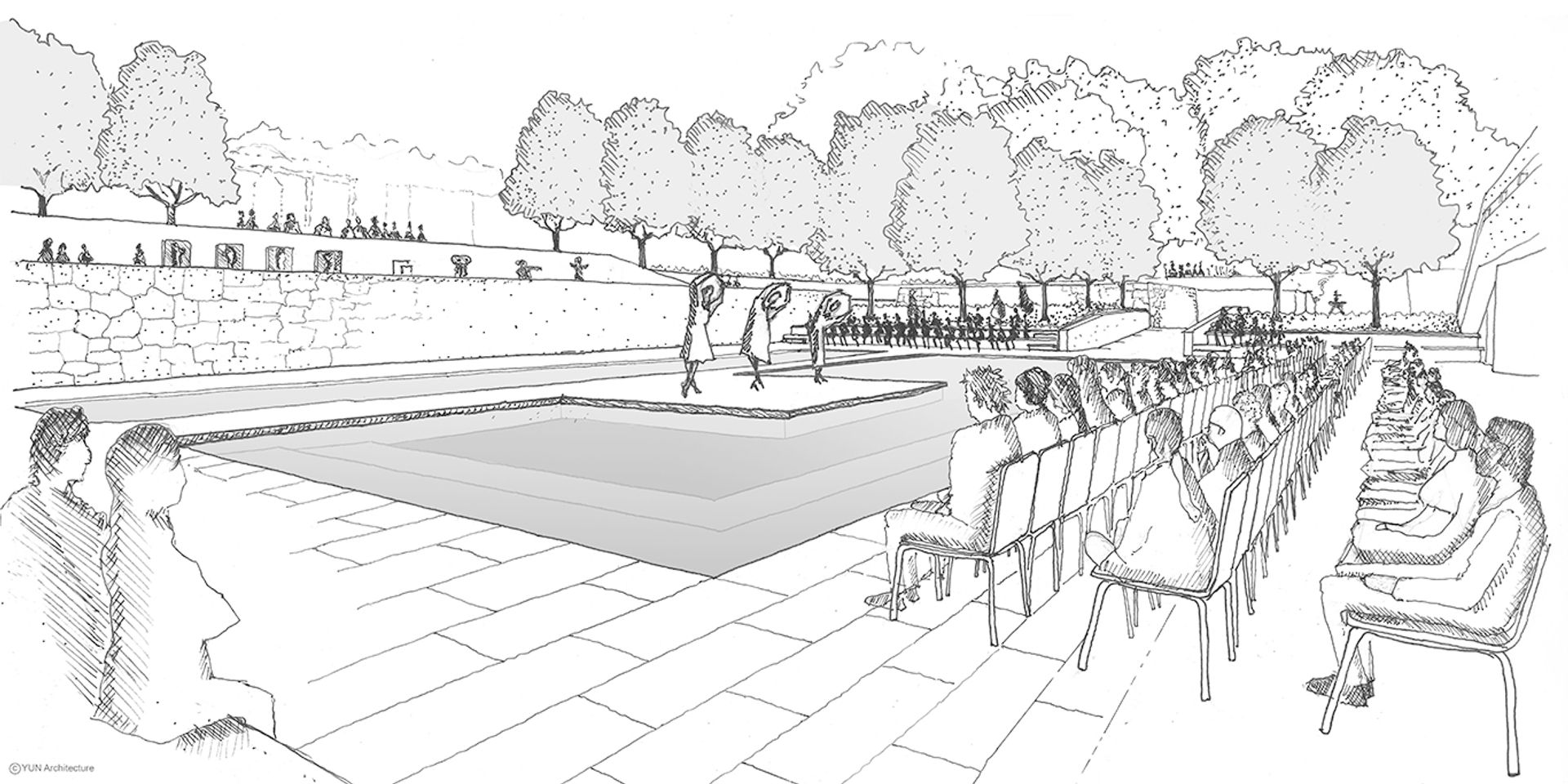

In a revitalisation masterminded by the Japanese architect and photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, the Hirshhorn would add a flexible central space for performance art and temporary exhibitions, a series of interconnected outdoor “galleries” for the museum’s bronze sculptures, and expanded reflecting pools and a performance stage.

A rendering of a proposed expansion of the reflecting pool that could transform it into a venue for performances Smithsonian Institution

Sugimoto’s design, which has undergone repeated revisions, would also create overlooks and ramps from the National Mall, replace the original perimeter concrete walls with new concrete walls, introduce stacked stone to replace an interior concrete partition wall, add other stacked stone walls, and reopen and modernise an underground tunnel below Jefferson Drive that connects the museum’s plaza with the garden.

The east garden would feature modern sculptural masterpieces; the central space, performance art and time-based media; and the west garden, contemporary work including large-format commissions, the Hirshhorn says.

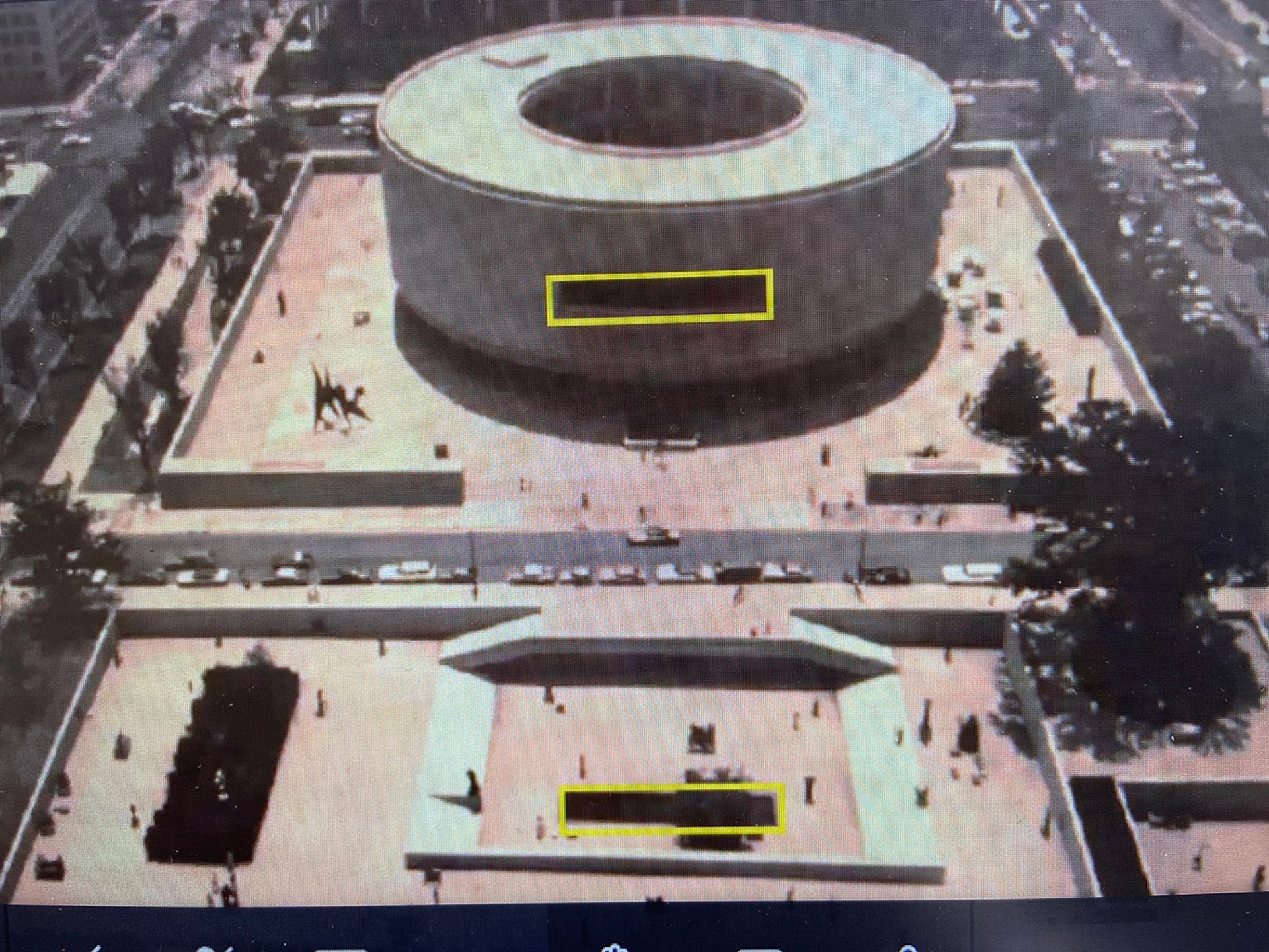

But champions of landscape architecture argue that some of the changes would divest the garden of its core identity. A key point of contention in Sugimoto’s design is the expansion of Bunshaft’s original rectangular reflecting pool, which intentionally echoed a horizontal window and balcony in the museum’s northern façade. The plan calls for an added apron of water on three sides of the existing pool plus a new U-shaped pool to the south that could be a staging area for performances with amphitheatre seating.

An illustration of the relationship between a window and balcony on the Hirshhorn's façade and a reflecting pool in the sculpture garden, as it exists now Cultural Landscape Foundation

Defending the original pool

The original pool “is a powerful and unifying gesture”, sharing a minimalist vocabulary with the rest of the garden and the museum, says Charles A. Birnbaum, president, chief executive and founder of the Cultural Landscape Foundation, a nonprofit advocacy and education group that seeks to valourise landscape heritage. “And you don't read that in any of the variations of the [Sugimoto] schemes that we have seen over time. They all have new geometries.”

Critics also blanch at the plans for the variegated stacked stone walls, which they say would war with Bunshaft’s unifying smooth Modernist concrete surfaces. But Dan Sallick, chairman of the Hirshhorn’s board of trustees, counters, “We believe the stacked stone is critical,” arguing that it provides a more evocative contrast to the museum’s Modern and contemporary sculptures.

At an online meeting on 3 December, the federal National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) approved Sugimoto’s preliminary site development plans with the exception of the proposed changes to the reflecting pool and inner partition wall. Commissioners asked that the Hirshhorn explore an alternative to the expanded pool design that would retain the historic dimensions of the existing one. It also recommended that the Smithsonian find a way to make the new stacked stone walls more compatible with, while still distinct from, the material that Bunshaft used for his historic perimeter wall.

One commissioner, Mina Wright of the federal General Services Administration, compared the Hirshhorn’s mockup images of stacked stone to something that “just reeks of Olive Garden [the chain restaurant] and that is not a good look on anybody.”

A mockup of the kind of stacked stone walls that Hiroshi Sugmioto is proposing for the Hirshhorn's sculpture garden, with Alberto Giacometti's Monumental Head (1960). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution

Now it falls to the Hirshhorn and Sugimoto to respond. (In addition to the NCPC, the US Commission of Fine Arts must approve the design, and another review process, in which the changes are being considered as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s overall South Mall Campus Master Plan, is underway under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.)

'A truly 21st-century garden'

The Hirshhorn is determined to forge ahead. “We want a truly 21st-century garden,” says Sallick, “with really exciting spaces where artists would want to create large-scale outdoor projects”. He said the redesign would essentially create “a new front door” for the museum by creating sightlines that would invite visitors to enter from the National Mall, and emphasised that Sugimoto had been deeply sensitive to the Japanese Zen influences in Bunshaft’s original design.

The project has drawn letters of praise from such figures as Glenn D. Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art; Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery of Art; the architect David Adjaye; and Kristopher Jon Takács, who leads the Washington office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which was Bunshaft’s architecture firm.

Reached by telephone in Japan, Sugimoto emphasised that his garden design is faithful to Bunshaft’s concrete aggregate perimeter wall: “I thought this was a very important design characteristic of this garden,” he says.

But Sugimoto adds that he has a mandate to update the sculpture garden to meet contemporary needs, including the performing arts, while also underlining that he has made many modifications in response to comments and that negotiations continue. “It’s a process of negotiating and talking and I have no answer yet," he says. "My opinion is just 10% or 20%. I tell people what I want to make."

“This restoration—Bunshaft is an artist and Lester Collins is an artist and I am the third artist to show up, so my position is one-third of the position. This is a new job for me to negotiate with the history. This is a very important and interesting process for me,” says Sugimoto, who has longstanding ties to the Hirshhorn. (He designed a new lobby for the museum that opened in 2018 and was the focus of a major survey at the institution in 2006.)

At the same time, he defends the enlarged pool and the stacked stone walls. Historical sketches show that at one point Bunshaft wanted to create a “huge” pool, the architect says. And the stacked stone walls offer what he views as a more striking “premodern medieval style” backdrop for the institution’s modern sculptures, in accordance with the Japanese Zen aesthetic, he adds. “If you cannot accept this key part of the redesign—I do everything 100% and I would have to withdraw from the redesign,” Sugimoto says of the stones. “Take me or not take me—I hope this won’t happen, but that’s what I have to say. To be or not to be.”

Eligible for a historic designation

Like Birnbaum, Liz Waytkus, executive director of the nonprofit group Docomomo US, which champions the preservation of Modern architecture, was among those questioning the redesign at the 3 December hearing of the NCPC. She pointed out then that the Hirshhorn and its sculpture garden had been deemed eligible for potential listing on the National Register for Historic Places.

“The frustration with the sculpture garden and those two elements is a rigorous explanation as to why they need to be altered,” she said in an interview. “The pool has a visual connection to the building—the relationship is critical and should absolutely be left alone. And the addition of the stacked walls would change the landscape and the feeling that you have when you’re in there.”

Waytkus says she supports proposed changes such as reopening Bunshaft’s original underground passage between the museum plaza and the garden and adding ramps for accessibility. But she challenges the need to create zones within the garden for what she calls “wildly different” types of art programming. “Not everything needs to be Instagram-worthy or flashy,” she says. “We do need places where we can sit and contemplate.”

Birnbaum emphasises that the Cultural Landscape Foundation champions the general need for changes to the garden and has limited its opposition to the expanded pools and stacked stone walls “to show that we weren’t being dogged”. “We’ve just thought, let’s keep our eye on what’s important here,” he says.

He argues that because the space essentially belongs to the public through the nation’s Smithsonian Institution, planners have an obligation to heed the objections. “This is not a private museum on Park Avenue,” he says. “It’s a public institution on the National Mall.”

His organisation was quick to question the letters of support that the Hirshhorn said it had received from defenders of the project. After demanding and receiving copies of those letters, the Cultural Landscape Foundation has now requested copies of letters and emails in which the institutions sought backing from its contractors.

Requesting letters and emails

“We are concerned that Smithsonian contractors could feel pressured by Smithsonian official to endorse the Sculpture Garden project in order to avoid the risk of being viewed less favourably for future work,” Birnbaum wrote in a 21 December letter to the Smithsonian’s general counsel. The group says it has also sent a letter to the Smithsonian’s Office of Inspector General asking it to investigate whether officials at the Hirshhorn and the Smithsonian have been guilty of an abuse of power or inappropriate behavior by soliciting Smithsonian contractors to write letters or testify in favour of the project. The Hirshhorn says it has no comment on the request.

Kate Gibbs, a spokeswoman for the museum, says that its next step will be to prepare its response to the NCPC. In an email, she said that “any urgency” in the approval process “comes from a small circle of preservationists looking to slow if not stop outrightly the deliberate creation of a public sculpture garden for the 21st century”.

“If you were standing in the National Mall today, you’d see the National Air and Space Museum undergoing a top-to-bottom multi-year renovation to our left, and to our right, renovations to the Arts and Industries Building and the Castle,” she says. “Smithsonian facilities are changeable spaces.”

The Hirshhorn estimates that the remaking of the sculpture garden will take three years but so far does not offer a cost estimate.

An aerial rendering of how the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden would appear when viewed from the National Mall under Hiroshi Sugimoto's proposed redesign Smithsonian Institution