An advertising campaign by Unesco that calls attention to illegal art trafficking has undergone further revision after accusations that it misrepresented the background of the objects pictured in the ads.

The campaign, titled “The real price of art” and conceived with the Paris ad agency DDB, depicts art objects in elegant Western interiors with captions indicating that they were looted from their countries of origin. Last month, Unesco hastily pulled back three images of objects that had been culled from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s permanent collection—a Buddha’s head, a funerary monument and a mask—after the Met complained and others pointed out that the works were not looted in recent years as the ads claimed and in fact had a much longer provenance.

Those high-resolution images, all in the public domain, were evidently harvested from the Met’s website, although the advertising text did not identify the Met as the owner of the objects. Also pulled from the ad campaign was an image of Pre-Columbian vessel from Peru that was apparently a stock image from the photo agency Alamy.

In swapping out the images last month and publicly expressing its “regrets” to the Met, the UN agency retained just one work of art of the five it originally used in the campaign: a 15th-century panel from the Ghent Altarpiece that was verifiably stolen in 1934 in Belgium.

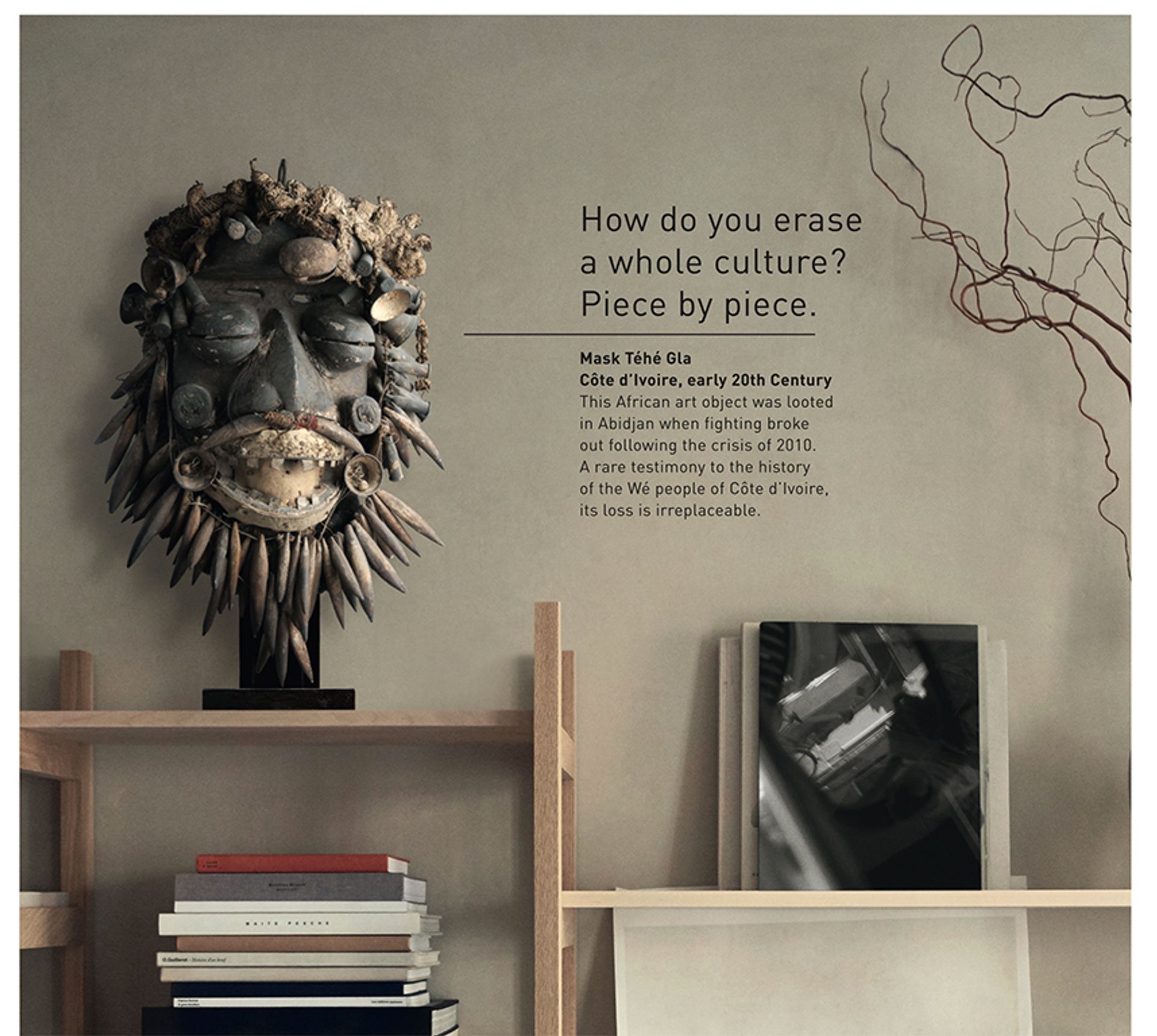

It immediately added two others: a statuette of a Sumerian Woman With Polos, or headdress, dating from 2650-2350BC (it was originally mistakenly labeled 2659-2350AD) that Unesco said was looted in 2014 from the National Museum of Aleppo in Syria, and a tribal mask dating from the early 20th century that it said was stolen in Abidjan in the Ivory Coast “when fighting broke out following the crisis of 2010.”

Lazare Eloundou, the director of culture and emergencies at Unesco, told The Art Newspaper then: “To avoid any misunderstanding on the purpose of the campaign, the campaign is now exclusively composed of items that have been looted.”

The problem was that neither of the added objects was looted: both still reside in museums in their country of origin, as the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA) pointed out last week in its monthly newsletter. “Unesco may well regret the embarrassment, but it doesn’t seem to have learned from it as the two hastily inserted replacement photos for the campaign testify,” wrote Ivan Macquisten, an industry consultant who is also an occasional contributor to The Art Newspaper.

The Aleppo statuette, which in reality is small, is reproduced in the ad at several times its size atop a bookcase next to a fuzzy armchair in a well-appointed living room.

The National Museum of Aleppo and the Syrian government’s directorate-general of antiquities and museums in Damascus, which oversees the institution, did not respond to requests for information on the whereabouts of the statue. Several scholars contacted by The Art Newspaper confirmed that the statuette remains in the museum, however, including Zainab Bahrani, a professor of ancient Near Eastern art and archaeology at Columbia University.

The statuette can also be glimpsed in a video about the reopening of the Aleppo museum last year. A separate video prepared by the Syrian tourism authority, the IADAA newsletter notes, quotes Khaled Al-Masri, director of Aleppo museums and antiquities, as stating that despite an attack on the museum with mortars and missiles a few years earlier, the collection inside was totally preserved rather than looted.

After the IADAA newsletter went out, Unesco changed the text of the ad depicting the Woman With Polos. Under the headline “Supporting an armed conflict has never been so decorative,” it had read: “This priceless antiquity was stolen from the National Museum of Aleppo when the fighting was at its peak in 2014, before being smuggled into the European market.” Now the underlying blurb says: “A priceless antiquity similar to this was stolen from Syria, when the fighting was at its peak in 2014, before being smuggled into the European market.”

A blurb in a Unesco advertisement after being changed to eliminate the contention that a statuette was stolen from the National Museum of Aleppo Unesco

Asked where this similar antiquity had resided before its reported theft, a Unesco spokeswoman said in an email, “If you think there was no looting in Syria of objects similar to the Woman in Polos, we leave it to you to state this in your article.” No further explanation was given.

Unesco has said that the ad campaign underlines the severity of the threat from illegal trafficking in art and artefacts and has been acclaimed by member states. “All images and texts used in the current campaign have been carefully chosen and drafted in cooperation with all the institutions concerned,” says a statement from the culture and heritage sectors of the agency relayed by the Unesco spokeswoman.

The director of the Musée des Civilisations de Côte d’Ivoire in Abidjan, Silvie Memel-Kassi, confirmed by email that the mask described in the campaign as having been looted from her museum is still in the collection. A similar mask by the same sculptor was stolen from the museum during an armed conflict in 2011, however, along with other objects from the institution, she adds.

A blurb in a Unesco ad says the mask depicted was looted after a crisis in 2010 in Abidjan. The director of the Musée des Civilisations de Côte d’Ivoire in Abidjan says it remains in the museum's collection, however. Unesco

Memel-Kassi emphasises that she authorised the use of the photo, which she says was originally shot in 2016 and distributed to advance an awareness campaign about stolen objects. That image also accompanied a recent article she wrote about illicit trafficking of Ivorian collections for The Journal of Art Market Studies.

“The National Museum of Côte d'Ivoire is a partner of Unesco, and therefore supports the campaign of this organization which, in my humble opinion, responds to the aspirations of member states,” she says in an email. “The image we have given enters into this concept of illicit traffic. This is why we did not hesitate for a single moment.”

Memel-Kassi adds: “The antique dealers who protest against the use of this image certainly have their reason which I ignore.”

Unesco also confirmed that Memel-Kassi “gave us her full permission to use the image of the mask, and agreed to the text accompanying the image”.

But representatives of the antiquities trade counter that the blurb accompanying the image of the mask is deceptive. They note that the text, under the headline “How do you erase a whole culture? Piece by piece,” reads: “This African art object was looted in Abidjan when fighting broke out following the crisis of 2010.”

Since the IADAA sent out its newsletter, another work of art has been added to the ad campaign: an Inca ceramic jug from Peru dating from 1470-1532 that Unesco says was looted in an illegal excavation at an unspecified date. The object is certain to be scrutinised by those associated with the antiquities trade.

“Several things indicate how poorly Unesco have handled this updated campaign,” Macquisten said in an email. “They still list the tribal mask as looted, when it was not. The Woman With Polos is depicted roughly at a scale of around three times its actual size,” and “the original caption was made up, as our evidence showed and as their alteration to it now shows.” He adds that the campaign was supervised by at least five Unesco officials named in the online version of the ad campaign, “none of whom acknowledges any real wrongdoing even now”.

The antiquities trade has long been at loggerheads with Unesco, of course, accusing the agency of overstating the dimensions of illicit trafficking in antiquities, including Unesco’s current $10bn global estimate, and undermining what dealers claim are legitimate sales.

Last month, Cinoa, the international federation of art and antiquities dealers associations, protested the inclusion of images of objects in the Met’s collection. “The campaign is fraudulent, with the desired intention to mislead the public on the provenance of works of art and to damage the credible reputation of the art trade and collectors,” Cinoa’s president, Clinton R. Howell, wrote then in a letter to the director general of Unesco, Audrey Azoulay.

Erika Bochereau, secretary general of Cinoa, says in an email that her group has been working with Unesco to “suggest effective and focused legislation that enables the legitimate trade to flourish”. She adds, “We however, cannot accept the insinuation of Unesco's latest campaign that the art trade operates in an untrustworthy way with criminal groups.”

The campaign, which opened on 20 October, is timed to the 50th anniversary of the 1970 Unesco convention against illicit trafficking in cultural property, which the UN agency marked in November.