Unesco has pulled back images from an advertising campaign intended to highlight international trafficking in looted artefacts after receiving complaints that it misrepresented the provenance of the works pictured. Among the objects used in the campaign were three from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York that were not stolen in recent years as the original ads indicated.

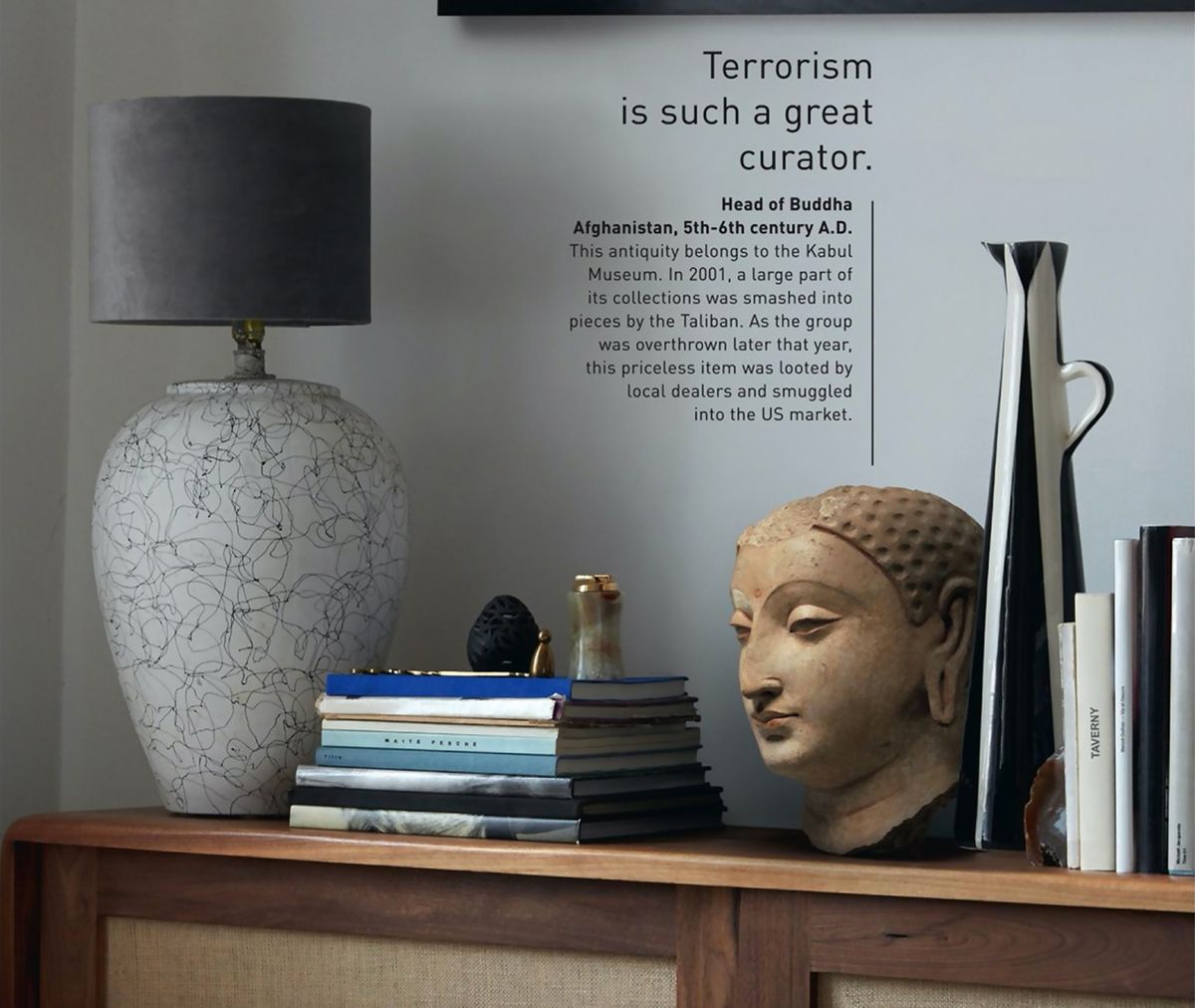

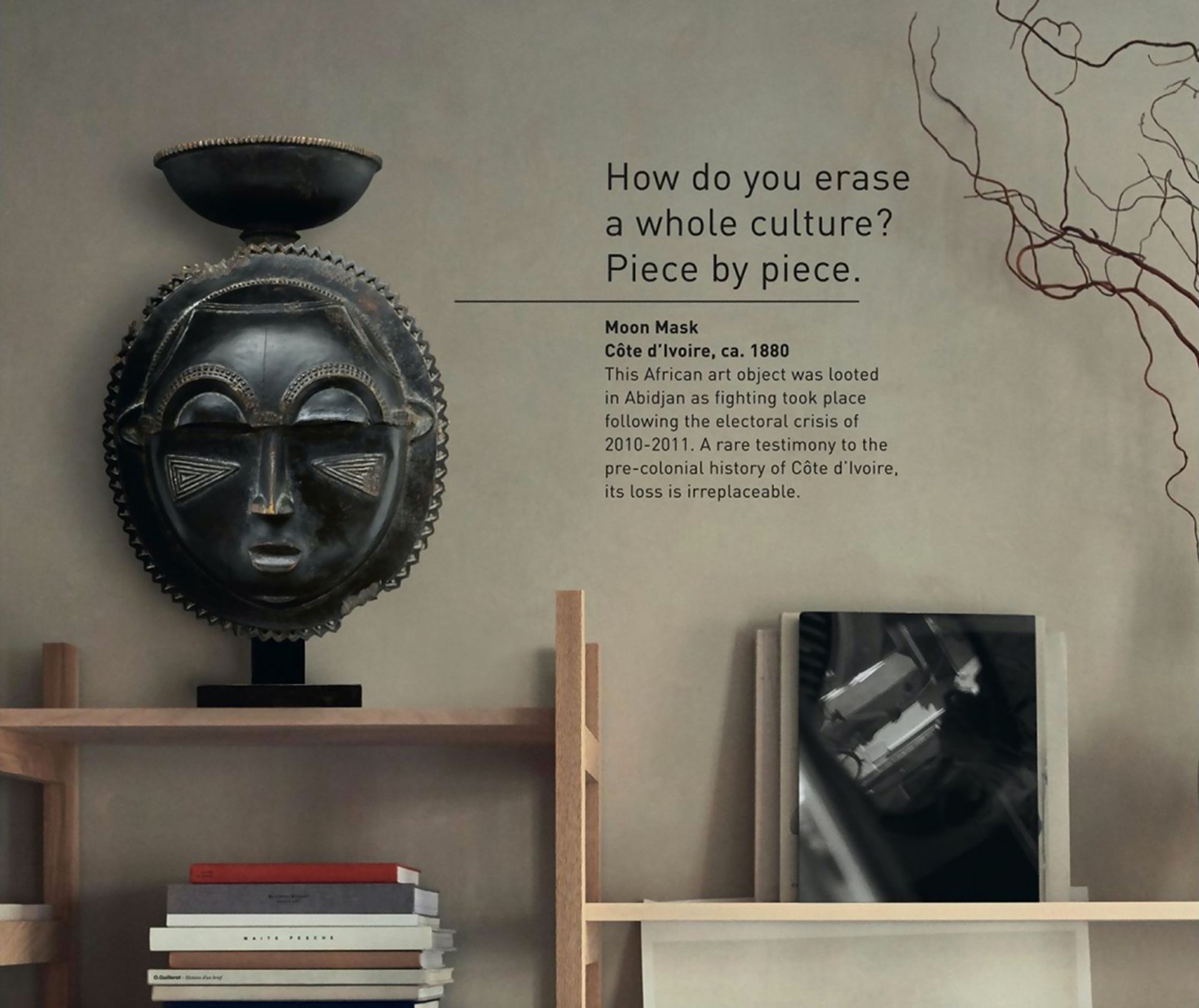

The ads, from a campaign billed as “The Real Price of Art”, initially depicted five different objects inserted into domestic interiors that viewers would associate with affluent present-day collectors. The Met was not mentioned, nor were the actual whereabouts of any of the works of art depicted.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired this Buddha head in 1930, and it is the first object that comes up when you search for similar objects in its digital collection

“The Real Price of Art campaign, created with the communication agency DDB Paris, draws on the language of the worlds of art and design to reveal the dark truth behind certain works,” Unesco says at its website. “Each visual presents an object in situ, integrated into a buyer's home. The other side of the decor is then revealed: terrorism, illegal excavation, theft from a museum destroyed by war, the cancelling of a people's memory... Each message tells the story of an antique stolen from a region of the world (Middle East, Africa, Europe, Asia and Latin America).”

The ads are keyed to the 50th anniversary of the 1970 Unesco convention against illicit trafficking in cultural property, which the agency is celebrating this weekend. An international conference on the theme of illegal trade is planned from 16 to 18 November.

A spokesman for the Met says: “When this came to our attention recently, we immediately reached out to Unesco to have the Met images removed from the campaign—and they assured us that that will take place.”

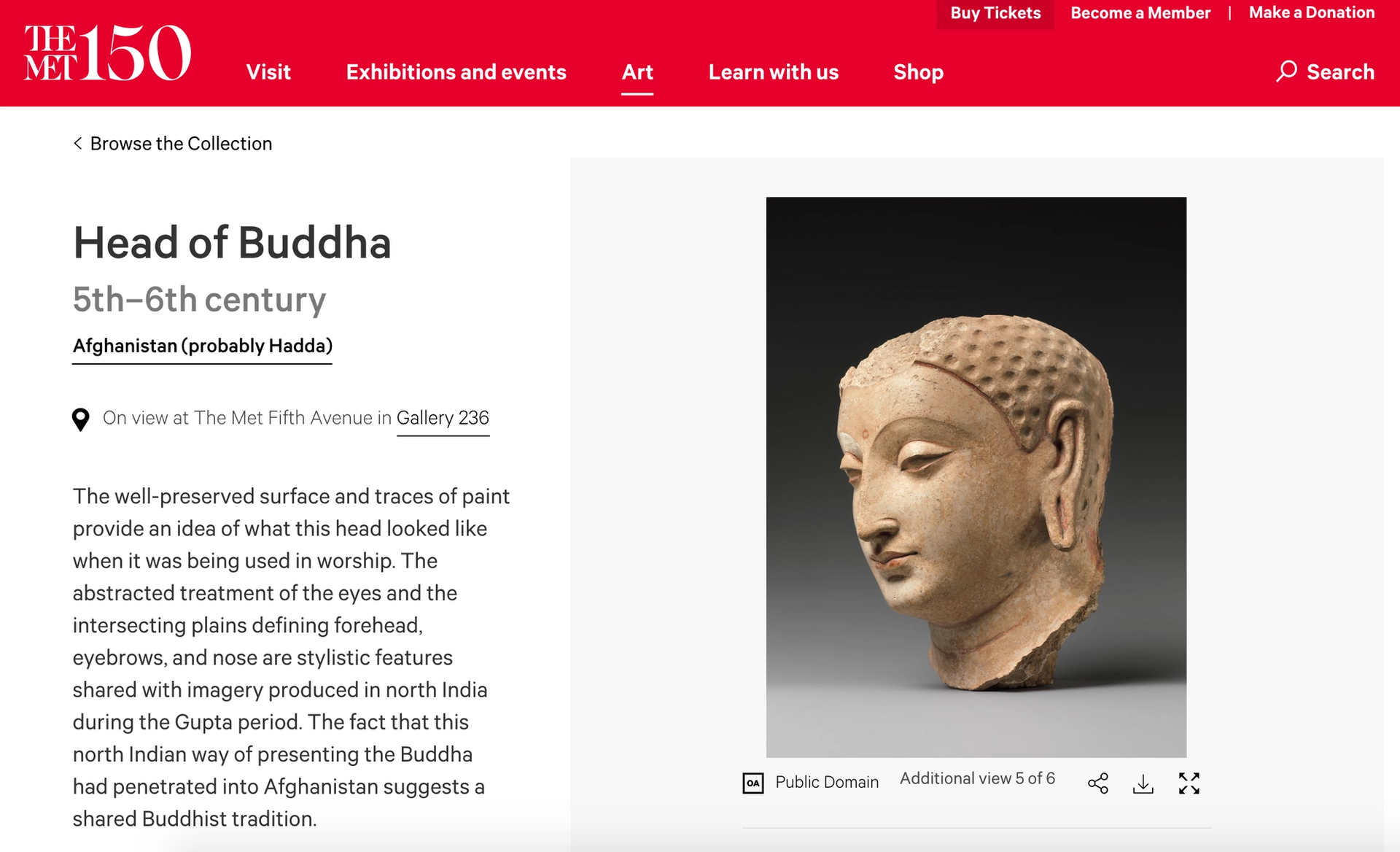

The museum makes many high-resolution images of objects in its collection that have entered the public domain available online; it remains unclear why Unesco or the DDB ad agency decided to use these specific works, but they are among the top results when searching for similar objects—such as “head of buddha or "funerary relief”—on the Met's website.

Cinoa, the international federation of art and antiques dealers associations, also protested the inclusion of the images. “The campaign is fraudulent, with the desired intention to mislead the public on the provenance of works of art and to damage the credible reputation of the art trade and collectors,” Cinoa’s president, Clinton R. Howell, wrote in a letter today to the director general of Unesco, Audrey Azoulay.

In a “clarification” at its website, Unesco said it “regrets the use of Met images that caused any misunderstanding”.

“In an initial version of Unesco's campaign, the ‘Real Price of Art’, some posters displayed items from the Metropolitan Museum of Art database, which is in the public domain,” it said. “Unesco's intention was to alert the general public by depicting objects of high cultural value, which should be on display in museums, presented in luxurious private interiors. Unesco had no intention of questioning the provenance of items in the Met collection.”

“After discussions with the Met, who is a valuable partner to Unesco, and in order to avoid any misunderstanding, Unesco decided to remove all pictures of items from the Met collection. Only three magazines had already been printed. The digital versions of these publications were modified.”

The original ads inaccurately described the provenance of the objects drawn from the Met’s collection, giving them a recent illicit history. For example, alongside an image of a Buddha head dating from the fifth to sixth century and originating in Afghanistan, which appeared in an ad perched on a sideboard next to books and a lamp, a description reads: “This antiquity belongs to the Kabul Museum. In 2001, a large part of its collections was smashed into pieces by the Taliban. As the group was overthrown later that year, this priceless item was looted by local dealers and smuggled into the US market.” The headline over the text proclaimed: “Terrorism is such a great curator.”

In fact, the Buddha head has been in the Met’s collection since 1930, according to documentation at the museum’s website. The acquisition clearly precedes the 1970 Unesco convention prohibiting trade in illegally trafficked art.

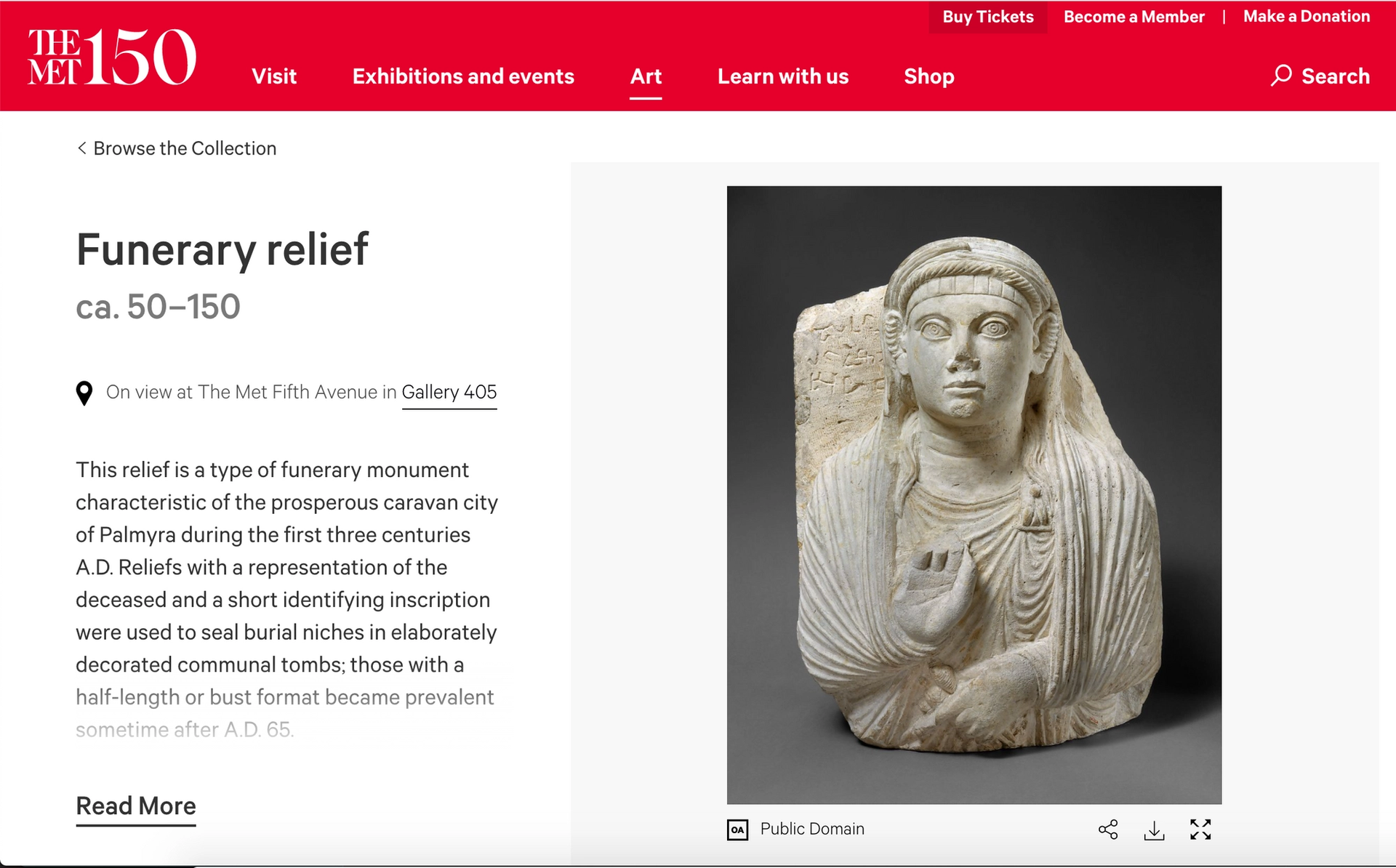

A funerary relief thought to be from Palmyra dated from AD50-150 as depicted in a Unesco advertising campaign. The ad text says that it was stolen from the National Museum of Palmyra by Islamic State militants, but the Metropolitan Museum of Art reports that it acquired the object in 1901. Unesco

Similarly, another ad in the series with the headline “Supporting an armed conflict has never been so decorative” depicted a funerary monument that the Met says is thought to be from the city of Palmyra in Syria and created during the first three centuries AD, placed on a bookcase next to some tasteful vases and a fuzzy armchair. “This priceless antiquity was stolen in the National Museum of Palmyra by Islamic State militants during their occupation of the city, before being smuggled into the European market,” the ad read. “The trade in antiquities is one of the terror group’s main sources of funding.”

But the Met’s online database shows that the sculpture was acquired by the museum in 1901.

The Met’s online database shows that this funerary relief from Palmyra was acquired by the museum in 1901

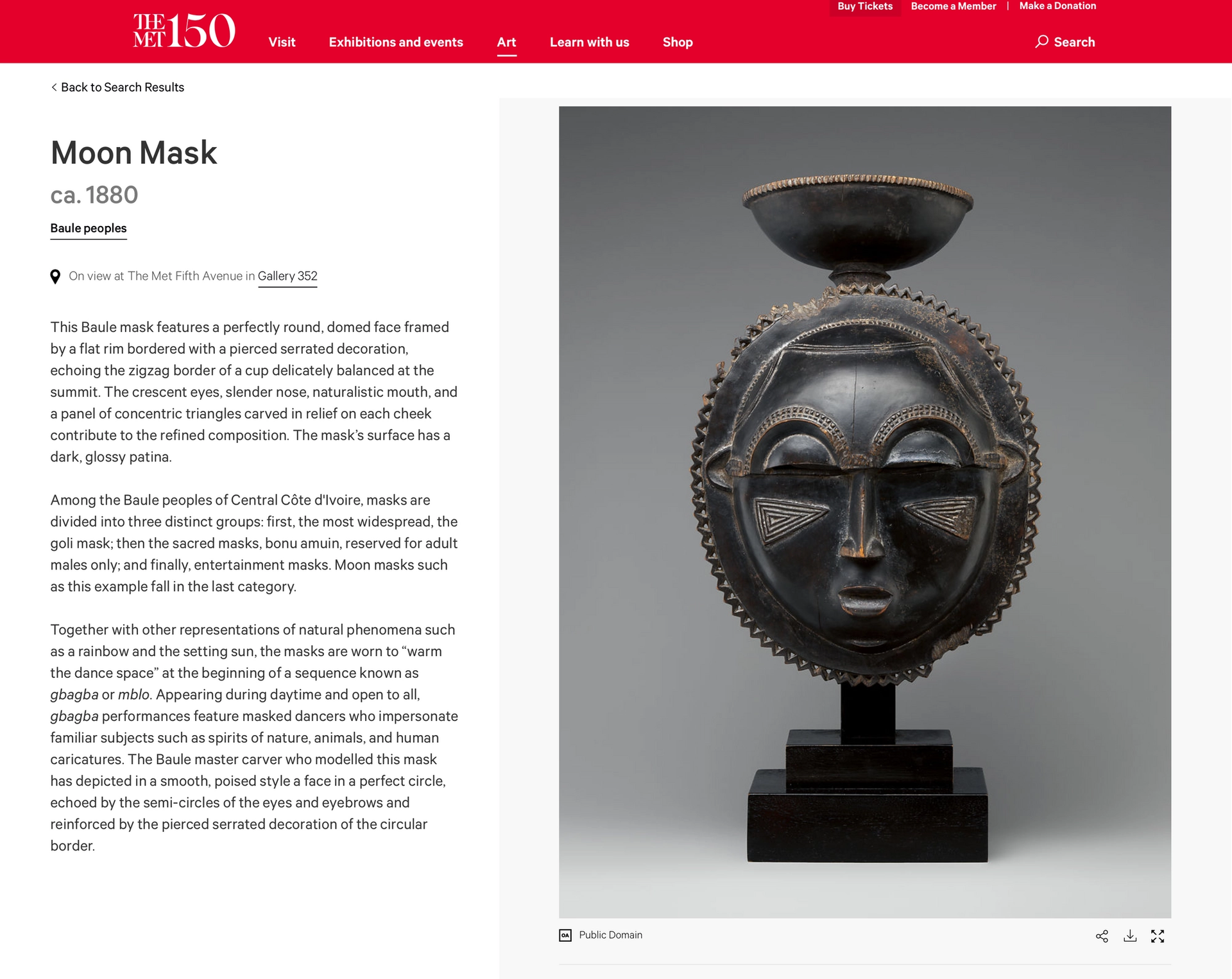

Also depicted in a contemporary interior was an Ivory Coast moon mask dating to around 1880. Under the headline “How do you erase a whole culture? Piece by piece,” the advertising text reads: “This African art object was looted in Abidjan as fighting took place following the electoral crisis of 2010-2011,” adding, “Its loss is irreplaceable.”

But the provenance information at the Met’s website relates that the mask was acquired by a US collector in 1954 and sold to another in 2003 before entering the museum’s collection in 2015.

A moon mask from Ivory Coast whose provenance dates back to 1954 and was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2015. Unesco erroneously describes it in an advertising campaign as having been looted in Abidjan after an electoral crisis in 2010-11. Unesco

Provenance information at the Met’s website relates that this Ivory Coast Moon mask was acquired by a US collector in 1954 and sold to another in 2003 before entering the museum’s collection in 2015

The other two images in the original ad campaign included a stock image from the photo agency Alamy of a Pre-Columbian vessel from Peru and a 15th-century panel from the Ghent Altarpiece by Hubert and Jan van Eyck that was (verifiably) stolen in 1934 in Belgium.

The van Eyck panel remains in the ad campaign, and two images of other objects have now been added online with texts indicating they were stolen. Oddly, one of them, a Woman With Polos that Unesco says was stolen in 2014 from the National Museum of Aleppo in Syria, is pictured with the date “2659-2350 AD,” reflecting some confusion in the research or editing process.

Asked for comment, a Unesco spokesman, Matthieu Gueval, said in an email that the Met had raised its objections to the ads two weeks ago and “We decided to remove other images and replace them, to be on the safe side, and to avoid any misunderstanding about the campaign.”

“We wanted to highlight that behind illicit trafficking of cultural objects are some critical issues like the financing of terrorism, the weakening of societies, etc.,” he adds. “We did not want to document any specific object (THIS mask, THIS funerary portrait), but rather highlight a category of objects that are extremely vulnerable to looting. The idea behind [this] was that these objects that may look nice on the shelves of a private apartment, have an important meaning for an entire people, and may hide a dark side if they come from unverified provenance.”

Asked whether it was Unesco staff members or employees of the DDB advertising agency who decided to harvest the photos from the Met’s website, Gueval said: “It is not as simple as that. A campaign is always a joint exercise between a client and an agency, there are back and forth, both on the texts and images.”

“Of course along the way there can be mistakes or shortcuts: this is an ad campaign, not a PhD thesis for the university,” he adds. “The point and key argument of the campaign remain clear and strong. Hope this is not overshadowed by secondary debates.”

In a phone interview later, Gueval added: “It was a shared thing. The choice of the images led to a misunderstanding. If we had chosen the Mona Lisa in a domestic apartment, it would have led to an impression that it belonged to the Louvre. Our objective was really to alert and mobilise the public.”

After indicating on Thursday that it would prepare a response, DDB said today that it would not reply to a request for an explanation of how the ads were conceived and designed.

Lazare Eloundou, the director of culture and emergencies at Unesco, said of the images in an email: “They were chosen to convey the understanding of the general public that artefacts are frequently looted for their mere aesthetic value–beyond their economic and cultural value.”

“To avoid any misunderstanding on the purpose of the campaign, the campaign is now exclusively composed of items that have been looted,” he says, adding: “It has received a very positive feedback by states party to the Unesco 1970 Convention.”

Unesco is meanwhile under scrutiny as it celebrates the 50th anniversary of the convention. Some dealers and independent researchers dispute the organisation’s $10bn estimate for the size of the illicit trade in cultural property, saying that it is vastly inflated and not based on reliable statistics.