After an initial statement that prompted more questions than answers, the directors behind the museums that postponed the exhibition Philip Guston Now have begun to put flesh on the bones of their decision. After stating in September that the exhibition would be postponed until 2024, they met with outrage that clearly surprised them, and have now announced that the tour would begin in May 2022 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, before its stints in Houston from October 2022, Washington from February 2023 and London from October 2023.

But there are still inconsistencies in their arguments. In a letter which appeared on 5 November, Matthew Teitelbaum, the director of the MFA Boston, wrote at length about the need to “thoughtfully reconsider how the work could be presented” when “the context in which we will present the work has changed since we first envisioned the exhibition”.

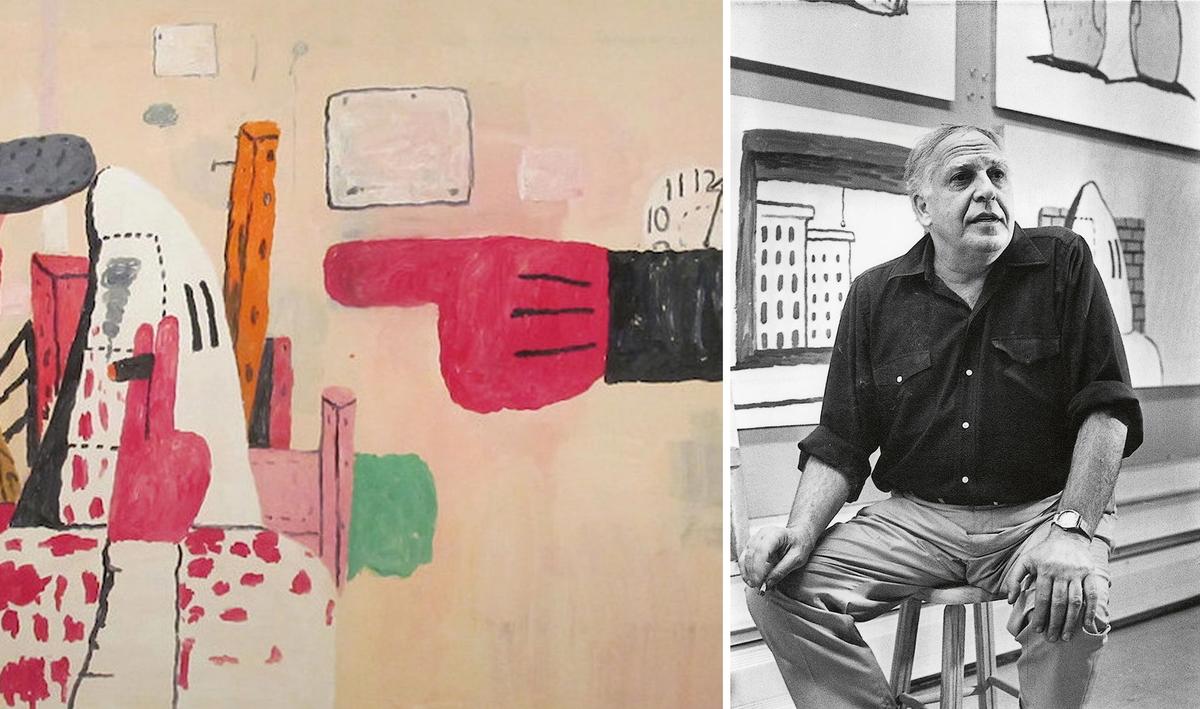

Kaywin Feldman, the director of the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, also offered her views, in lengthy interviews. Among the reasons she gave on the Hyperallergic podcast was: “In today’s America, because Guston appropriated images of Black trauma, the show needs to be about more than Guston.” The images she means are those paintings in which Guston features Ku Klux Klan figures.

Teitelbaum, meanwhile, evoked Guston’s work as a whole and wrote of how conversations about Guston’s work with people from numerous constituencies had brought to the surface “numerous expressions of unease and anxiety, and in some cases, intimations of vulnerability” in the face of “images of Ku Klux Klan figures, of social unrest, racial conflict, the profound challenges of social polarisation—and even invocations of the Holocaust.”

Teitelbaum’s understanding of Guston’s work seems far more nuanced that Feldman’s. Because while the artist explored Klan violence against Black people in his work, it is too simplistic to describe his works as “appropriations”. The Klan are most associated with atrocities against African Americans, of course. And it is only right that the museums should respond quickly to the ramifications of George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter movement. Indeed, long before Floyd’s death, the curators, clearly conscious of the need for Black voices in discussing Klan imagery, invited the African American artists Trenton Doyle Hancock and Glenn Ligon to write about these images for the show’s catalogue.

But Guston’s Klan imagery is bound up with anti-semitism and Jewishness as well as his horror at violence against Black people. In his collaboration with Reuben Kadish on The Struggle Against War and Terrorism in 1935, one of the Klan figures clasps a swastika. Guston gave the key explanation of his Klan figures—the “little bastards”, he called them—in the late 1960s, citing the Ukrainian Jewish journalist Isaac Babel, who had joined the Cossacks and witnessed their antisemitic atrocities: “I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan,” Guston wrote. “What would it be like to be evil?” In the catalogue for Philip Guston Now, the curator Mark Godfrey explores the hoods in the context of Jewish golem figures; the artist Art Spiegelman ponders Guston casting himself as a Klansman in the context of his “regret” at changing his name from Goldstein to Guston, to accommodate the anti-semitism of his wife’s parents.

When Feldman talks about “today’s America”, that country is not just the one in which George Floyd can be brutally murdered but also one in which US President Donald Trump sees “very fine people” among those white supremacists who marched into Charlottesville chanting “Jews will not replace us”. Guston was trying to get under the skin of their equivalents in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As his daughter Musa Mayer pointed out in a statement when the show was first postponed, “he dared to hold up a mirror to white America, exposing the banality of evil and the systemic racism we are still struggling to confront today”. And Teitelbaum was right to highlight that images of the Holocaust—including those piled legs in works like Pit (1976)—were as common in Guston’s late work as the hoods were in the short period between 1968 and 1971.

In a recent open letter to the Brooklyn Rail, dozens of artists and writers argued that Philip Guston Now should be reinstated and the museums’ staff should prepare themselves to engage with the public and “do the necessary work to present this art in all its depth and complexity”. They were right: the more courageous response from museums would not be to re-curate the show in the coming years, but to re-interpret it for now.

And when Teitelbaum describes what form the reframing of the show might take from 2022, one wonders again what got into the museums to delay the show until 2024. In his message, Teitelbaum suggests that the new Philip Guston Now would have “more diverse voices contributing to the preparation of historical framing materials that allow us to appreciate the context in which Guston worked and achieved his vision; more fellow artists’ voices within the exhibition to share what the work means to them; more interactive moments with visitors that allow them to express views on how the images create their effect. More video clips with contemporary voices, including historians. More opportunity to create teaching modules for students within the Museum and with school audiences. More staff input to allow us to continue our work in celebrating and representing America’s history in ways both responsive and responsible.”

All of which is welcome, but why lurch towards lengthy postponement, rather than making urgent use of a delay already caused by the pandemic to recontextualise the show in the ways that Teitelbaum suggests? After all, the NGA version would not have opened until July next year, rather than June this year; the Houston version was already delayed by 17 months to March 2022.

It is cheering that we will not have to wait as long as we first thought for Philip Guston Now. But as the artists’ and writers’ letter to the Brooklyn Rail proves, there are passionate, diverse, learned voices itching to engage with Guston right now, and the museums have ample skilled educators and technicians to deliver the kind of re-interpretation the MFA director describes.

This was a moment for the museums to show bravery and fleet-footedness; to hold up their hands about their organisational inequities; to look their diverse publics in the eye. And to question themselves unflinchingly, just as Guston did in these extraordinary, troubling works.

• For more on the Guston controversy, listen to our podcast What does the Philip Guston delay tell us about museums and race?

• To hear Robert Storr speak about his book on Philip Guston, listen to This is America: Grayson Perry on race and class and for an extract from the biography, see Philip Guston’s fascination with the ‘funnies’ was key to developing his distinctive later style

UPDATE: This is an updated version of an article that appeared in the November 2020 issue of The Art Newspaper