The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) has announced that it is deaccessioning three works–by Andy Warhol, Clyfford Still and Brice Marden–to generate $65m to finance care of its collection, salary increases for underpaid staff members, diversity and equity initiatives and acquisitions.

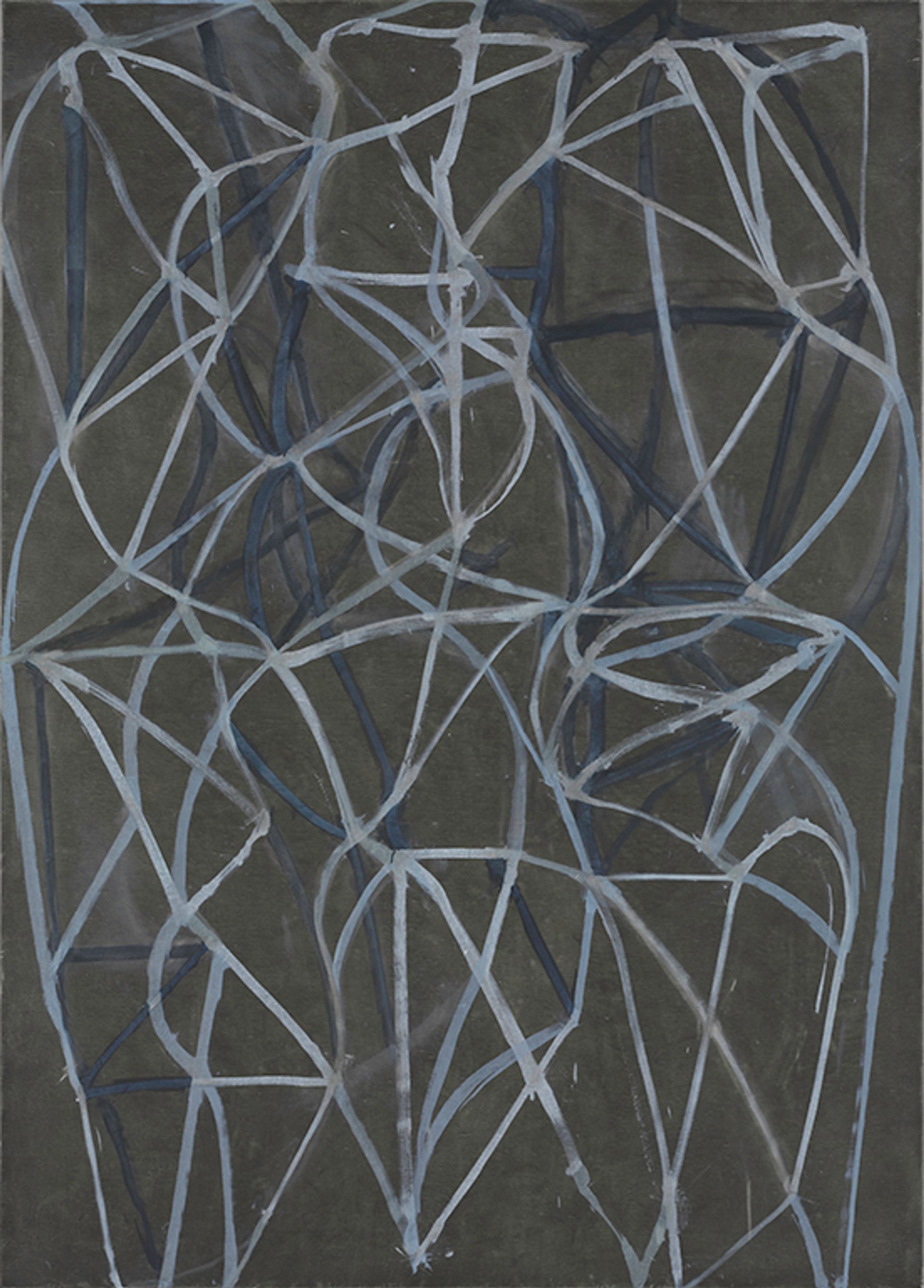

The museum says all the works will be sold this autumn through Sotheby’s. The works–Warhol’s The Last Supper (1986), Marden’s 3 (1987-88) and Still’s 1957-G (1957)–were selected by curators “to ensure that the narratives essential to the understanding of art history could continue to be told with depth and richness” by the BMA, it adds. The plan was approved by the museum’s board of trustees on Thursday.

The Warhol will be offered in a private sale. The Still, estimated at $12m to $18m, and the Marden, estimated at $10m to $15m, will be auctioned.

“It was an incredibly long, searching process,” Christopher Bedford, the museum’s director, said of the deaccessioning decision in an interview today, “with conversations occasionally heated, as they should be.”

The move follows a decision by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) in April to temporarily suspend the censures or sanctions it imposes when a museum uses proceeds from the sale of works for purposes other than buying more art. The moratorium on such sanctions, an acknowledgment of the financial squeeze that museums are facing amid the coronavirus pandemic, extends to April 2022.

The AAMD said then that it would also refrain from censuring or sanctioning any museum—or museum director—that decides to use restricted endowment funds, trusts, or donations for general operating expenses.

Taking advantage of this relaxation of rules, the Brooklyn Museum recently announced that it was selling 12 works at auction to finance care of its collection, including a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder that was the sole work by the artist in its holdings. The decision, which followed staff cuts at the museum, raised eyebrows even though it was in line with the AAMD’s changed guidelines.

The Baltimore museum has managed to avoid layoffs and furloughs but says it needs to heed “ongoing calls for radical thinking and change across the arts and culture sector”. Of the $65m that it hopes to raise through the sales, $10m will go to its acquisitions fund, allowing it to “rebalance” its collection by seeking out more works by women and people of colour–“particularly as they interweave with the history and present of Baltimore”, a majority black city, the institution says in a statement.

Around $54.5m would be used to create a new “Endowment for the Future” for the direct care of the collection, it adds. The BMA projects that this would generate approximately $2.5m in annual income that will be used to offset costs for research, conservation, documentation and exhibition of artworks as well as the salaries of 46 staff members including curators, registrars, conservators, preparators, art handlers, administrative staff and fellows. And $500,000 will go toward a new initiative to promote internal and external diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion (DEAI) initiatives.

“I was beginning to feel even before Covid-19 that there was a really indefensible asymmetry between what we declared about our identity and how we operated within our institution behind the walls,” Bedford says of the DEAI initiatives.

As part of the Endowment for the Future, the BMA will also draw approximately $590,000 annually toward eliminating admission fees for its special exhibitions and most public programs and extending its evening hours to 9 p.m. one weekday each week to meet the needs of the local public, it says. The museum reopened on 16 September after a months-long shutdown necessitated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The decision to sell the three works was first reported by The New York Times.

The Baltimore museum says the loss of the three works will not prevent the museum from presenting a textured historical narrative of post-war art. “The BMA has a significant post-war and Modern art collection with important examples of Abstract Expressionism, Post-Minimalism and late works by Warhol,” it says.

Nonetheless, the move is likely to unsettle some deaccessioning watchdogs. The Marden painting is the only one by the artist in the BMA’s collection–it also owns 16 of Marden’s works on paper–and the Still is the only work by the artist in any medium in the museum’s holdings. (A spokeswoman says the BMA has 91 works by Warhol, including other late paintings in addition to The Last Supper.)

Brice Marden, 3 (1987-88) Courtesy of Baltimore Museum of Art

The Warhol being sold, purchased by the museum in 1989, “is close to meeting the definition of collection redundancy,” Bedford says. Devoting a full gallery to Warhol, he adds, would not fit into the museum’s curatorial ethos.

As for the work by Marden, 81, acquired in 1989, the director notes that “there are no rules that make the work of a living artist untouchable.” “We are very sensitive to Brice Marden’s place in history,” he adds. “But it’s established with great force and clarity through our holdings of works on paper,” which he describes as “compelling and subtle”.

For the Still, meanwhile, a 1969 gift from the artist, curators “have broadened the definition of redundancy to focus more on the broader narration of art history than on focusing on one particular artist”, Bedford says, noting that the museum has rich Abstract Expressionist holdings but hopes to enrich its narrative of the movement by adding artists who had been excluded.

The museum previously stirred controversy in 2018 when it sold seven paintings by prominent artists to help fund purchases of works by underrepresented artists of colour. Now it is seeking equity on another front, redressing salary imbalances within its staff.

“This includes individuals in front-of-house positions throughout the museum as well as roles across education, marketing, advancement, facilities, and other administrative areas and departments,” the museum says in a statement. Bedford cited the example of museum guards, whose pay will rise from $13.50 an hour to $20 an hour by July 2022.

“We have not experienced the insurrection you’ve seen at other institutions, but we do have a very vocal staff,” he says. “We’ve heard a great deal in the last six months, and of the greatest achievements of the movement sweeping the museum world is that people have finally found their voice.”

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (1986) Courtesy of Baltimore Museum of Art

Across the country, museum employees are rallying not just for greater pay equity but for greater diversity within the ranks of their overwhelmingly white-dominated institutions. In addition to acquiring and exhibiting more works by women and people of colour, Bedford says, he is seeking “a radical policy shift that will change the constitution of our staff”.

“We have to bring people not commonly shepherded through the hierarchy into the institution so that the colour and the cadence of our staff completely shifts,” he says.

Christine Anagnos, the director of the AAMD, said in an email today that the museum’s plans are in alignment with what the museum association authorised in its April resolutions.

“But this is also clearly part of a wider set of issues facing the field, and I think any conversation about deaccessioning—or, really, any area of art museum operations right now—has to be seen in the context of the two big present challenges,” she says.

“One is the pandemic, and the other is the ongoing work to address a range of DEAI needs; both are important and both require resources. Given that, whether the focus is Brooklyn or Baltimore, what these museums are doing makes some sense.”

“In both cases,” she says, “these new approaches make use of AAMD’s resolutions, and then we will have to evaluate, together as a field, whether these temporary measures make sense in the long run.”