Philip Guston (1913-80) knowingly risked his art-world standing and livelihood in 1970, when he first exhibited paintings abrasively different in style from those that had won him a place among luminaries of the so-called New York School of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s.

Most critics and artist contemporaries greeted his new work with punishing responses but, as the painter and art historian Robert Storr—who published an earlier monograph on the artist in 1986—recounts in this critical biography, Guston lived to see admiration begin to revive. He died shortly after the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (not then the prestigious institution it has since become) opened a retrospective in 1980. But he could merely dream of the eminence accorded his work posthumously as a hinge between modernist painting and what has come after. Riven by doubts and ambivalence, Guston took a jaded view of predictions of his future influence when they did appear, as in the New York New Museum’s 1978 exhibition ironically called “Bad” Painting.

“American Abstract art is a lie, a sham...”PHILIP GUSTON

Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting appears in the run up to Philip Guston Now, a career survey due to open in London at Tate Modern next year (4 February-31 May 2021) before travelling to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (3 July-3 October 2021), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (7 November 2021-6 February 2022) and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (6 March-30 May 2022). As the survey show rolls round, readers of Storr’s book can confront eyes-on many of the works crisply illustrated here.

By the luck of a scantly published young critic, I happened to attend the Marlborough Gallery exhibition in Manhattan where Guston unveiled the work that would explode—in a double sense—his position in the post-1945 US art world. I arrived early, knowing a little of Guston’s abstract work, and felt as baffled as anyone by the big canvases sporting ham-fisted images of glumly risible Ku Klux Klansmen at home or cruising cityscapes cluttered with rubbish cans, nail-studded lumber, heaped-up body parts, faux-Stone Age architecture and other figural flotsam. “Shoes. Rusted iron, Mended Rags... Bricks, bent nails and pieces of wood... Cigarette butts... Empty booze bottles,” were among items he had put on a list, found following his death. Yet the lushness of Guston’s colour and touch, and his confident address of big pictorial expanses, cast a spell that outlasted bafflement long after I fled the thickening crowd, social tension and cigarette smoke of the gallery opening. (I met the painter himself only several years later.)

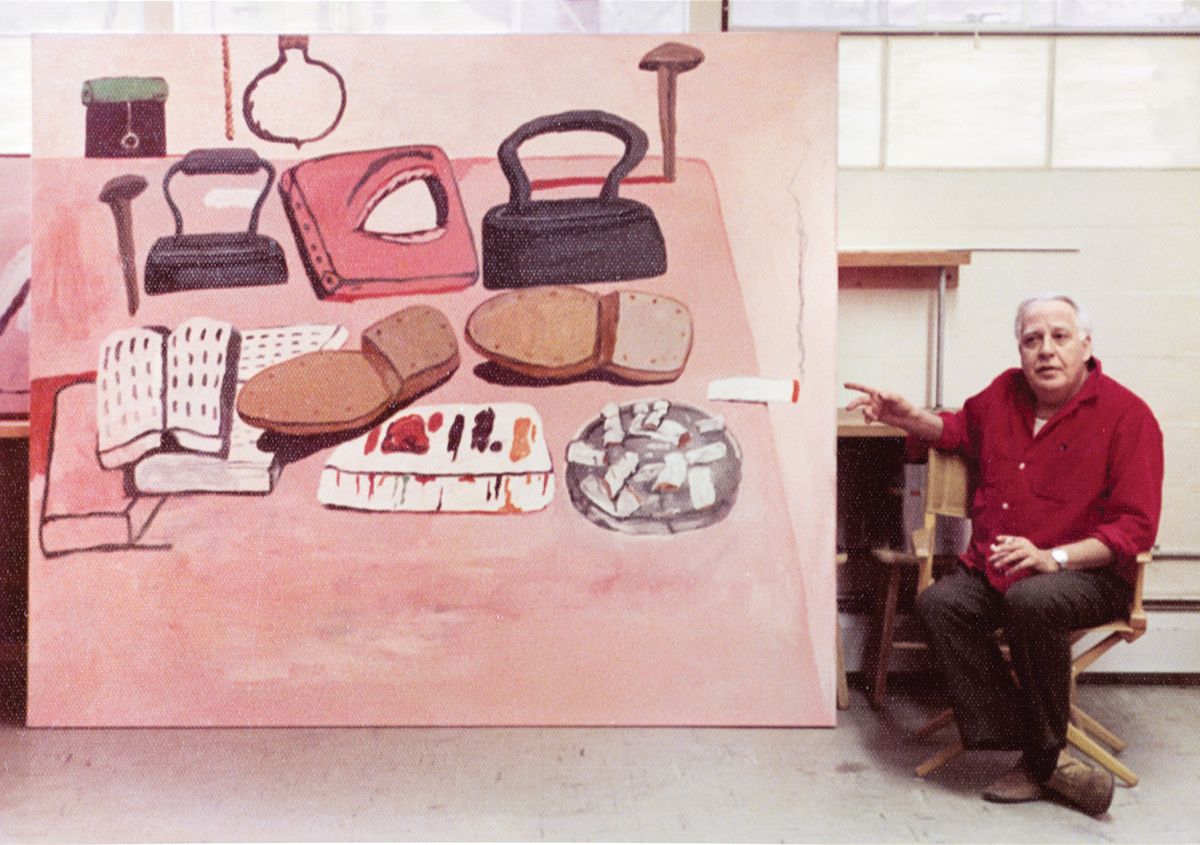

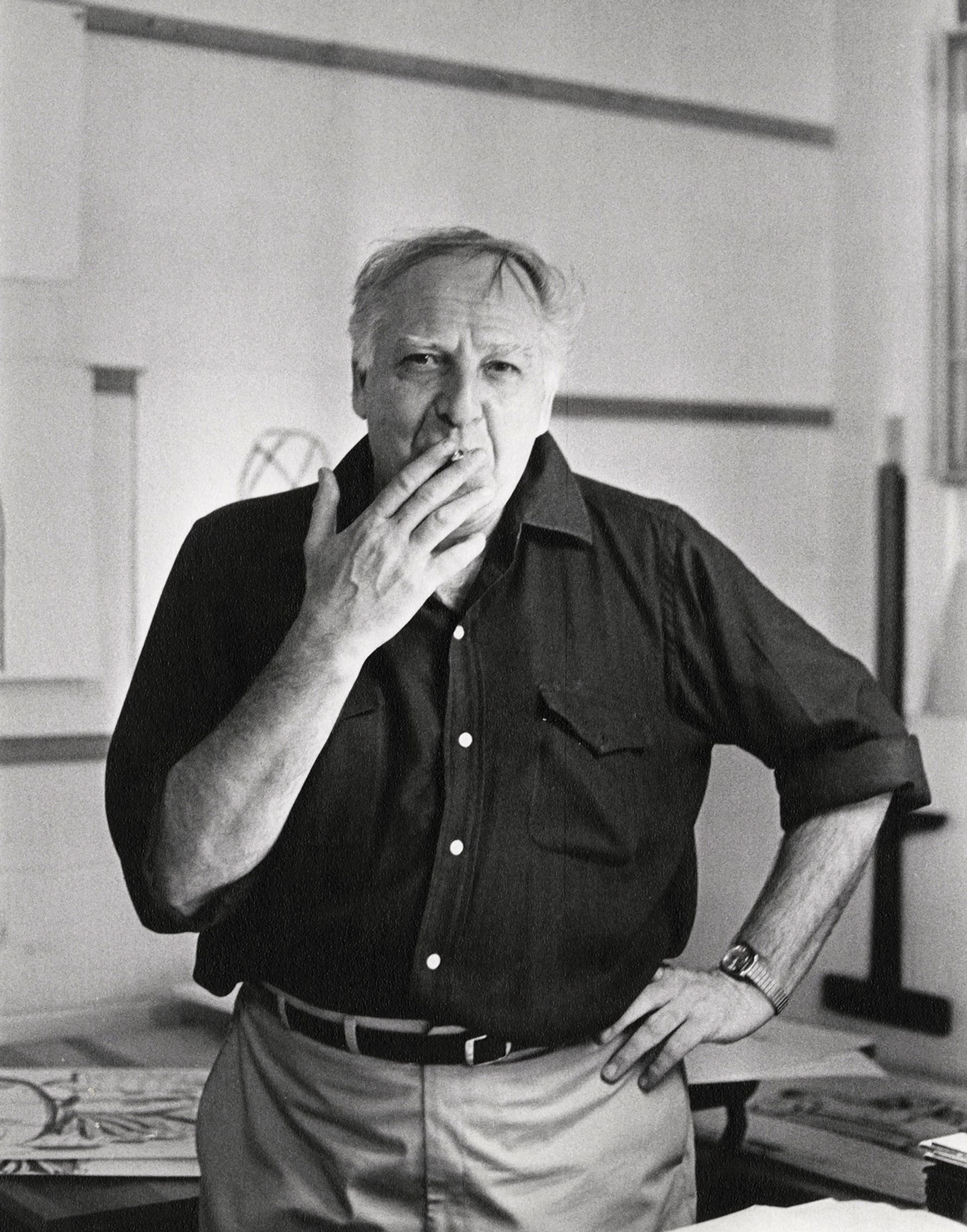

Philip Guston in his studio © Barbara C. Sproul

Fearing the worst, Guston had arranged to sail with his wife to Europe on the morning after the event. They were abroad for nine months, but news of the critical reaction eventually caught up with him. Two headlines evoke its scope: “A Mandarin Pretending to be a Stumblebum” on the review by Hilton Kramer in the New York Times and “Liberation from Detachment” in the New Yorker, on an article by Harold Rosenberg, a long-time friend of the artist.

“Kramer excoriated the formerly refined Guston of the 1950s,” Storr writes, “for having crossed over to the camp of vulgar aesthetic slumming epitomised for him by Pop Art. [His review] was... carefully aimed to do the maximum damage by a man with an insider’s awareness of the insecurities and prejudices of readers among the old guard Abstract Expressionists and their followers.” Rosenberg took a wider, friendlier, rhetorically cooler view, writing that “The separation of art from social realities threatens the survival of painting as a serious activity... Painting needs to liberate itself of all systems that place so-called interests of art above the interests of the artist’s mind. Abstract Expressionism liberated painting from the social-consciousness dogma of the Thirties; it is time now to liberate it from the ban on social consciousness. Guston... has managed to make social comment seem natural to the visual language of post-war painting.” Critical controversy over his art has pivoted ever since around that last assertion.

Some visitors to Guston’s 1966 exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum had noted figural rumblings among the dark, turbulent abstractions he presented there. Surging brushwork and a clumping refusal to settle aesthetically had supplanted the loose lattices of florid colour that the public had come to regard as Guston’s signature style. The weighty, uncontained formal incidents that define Guston’s mid-1960s paintings Storr describes “as the culmination of ambivalent meditations on cryptic forms that seemed to come from nowhere and belong nowhere”.

“You know, Philip, what your real subject is? It’s freedom!”Williem de Kooning

Guston warned admirers of his creative restlessness, declaring in 1960: “There is something miserly and ridiculous in the myth we inherit from abstract art... That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself... But painting is ‘impure’. It is the adjustment of impurities which forces painting’s continuity. We are image-makers and image-ridden.”

The paintings, first shown in 1970, and nearly all that would follow, burst with “impurities”—personal, cultural and phantasmal. Recalling the Marlborough show’s aftermath, which spelled several years’ exile from the art market, the artist would habitually mention the approval of his friend Williem de Kooning, who told him, “You know, Philip, what your real subject is? It’s freedom!”

Robert Hughes, the art critic for Time and another of the era’s loudest cultural voices, wrote that “In three minutes of film... the movie camera can disclose more of the reality that appals Guston than his whole exhibition has done. As political statement, they are all as simple-minded as the bigotry they denounce.” But art’s abject misperception by a spiritually impoverished mercantile society was part of “the reality that appals Guston”. So, too, was his guilt-ridden sense of his own moral position as a husband, father and self-destructive monster of creative obsession.

Storr’s title, A Life Spent Painting, is a reminder of this fact for those who knew Guston. Only after several years of intermittent, intense conversations did he mention, uncomfortably, to me that he had a grown daughter, Musa Mayer. (Her 1988 book, Night Studio: a Memoir of Philip Guston, is an emotionally complex and remarkably true portrait, and a source for Storr and for this review.)

Looking back at Guston’s youth and prodigious early work, Storr shows how Kramer and Hughes so elaborately misread Guston. The critics apparently knew little or nothing of Guston’s early paintings of Klansmen, based on his witness of their strike-breaking and other violent misdeeds in 1920s Los Angeles. The Klansmen resurfaced, transfigured, at the turn of the 1970s, implicating even Guston himself as he imaginatively entered their world of sullen, fiendish wickedness. “American Abstract art is a lie, a sham...” he wrote in notes, found posthumously, from the 1970s, “A lie to cover up how bad one can be... It is an escape from the true feelings we have, from the ‘raw’, primitive feelings—about the world, and us in it. In America.”

Philip Guston in his studio © Barbara C. Sproul

Writing with drive and clarity, Storr records the historical background of Guston’s art, never losing sight of “the interests of the artist’s mind”, from lifelong fascination with newspaper comics to Leftist political sympathies that stretched back to his high school days in Los Angeles and his formative stints as an assistant to the Mexican muralist, David Alfaro Siquieros, and as a Works Progress Administration artist during the 1930s. An unusually detailed and richly illustrated chronology, compiled by Amanda Renshaw, lays out links between the artist’s private and public lives.

“[He] was in constant pursuit of his true identity,” Storr writes, “or, in line with the precepts of the existentialist philosophy he gravitated toward in the 1950s, always seeking to create himself anew from the meagre, damaged legacy that he began with,” as the son of a depressed, underemployed Russian immigrant trash collector who hanged himself when the artist was 10. “To that end he was always on the lookout for a poetics hospitable to his inherently expansive, cosmopolitan, and, above all, metamorphic imagination.”

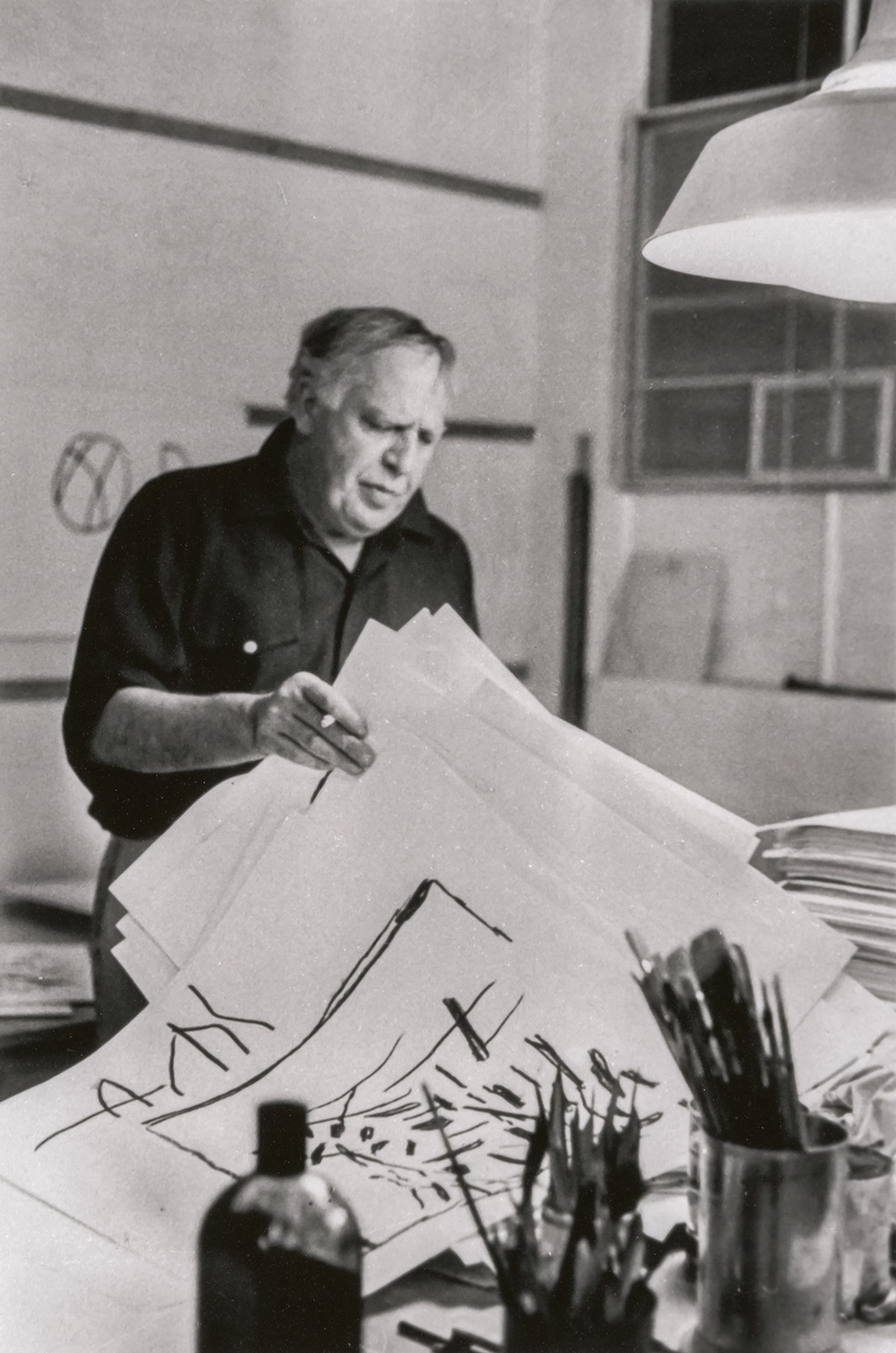

Storr gives a fine account of Guston’s prolific drawing practice as the path to the radical turn his painting took—the “metamorphic” manner that permitted a return of the unexpressed that abstraction had tamped down. “My painting comes out of drawing,” Guston told an audience of art students in 1974: “I couldn’t live without drawing.” Recent events have already overtaken Storr’s rich contextualisation, and that of every other commentator. Guston’s Klan-related imagery remains more “culturally relevant” than he could have, or would have, wished to imagine. The caustic caricatures Guston devoted to the corruption of Richard Nixon and his administration now look premonitory of recent, even cruder, political abominations. Storr gives these remarkable works, peripheral to Guston’s art in content but not in style, their proper weight in a career propelled by incessant drawing.

Storr even traces the weird dynamism of Guston’s late style to his work of the 1940s. “After years of learning from others how to make a picture,” Storr writes, “Guston began to teach himself how to unmake one—yet have it remain a painting in all the ways that count. He taught himself to conjure painterly incident, find and lose the form, inscribe and erase outlines, heed the imperatives of his medium’s materiality, and simultaneously identify and defy the intrinsic parameters of the support without there being any narrative other than that of the act of painting itself.”

As his 1970s paintings grew more inventively grotesque—and initially repellent to collectors—Guston used to say that he wanted “to make paintings you couldn’t count money in front of”. It was the heyday of US corporate art collections, whose curators favoured anodyne colour-field abstraction and photo-realist painting, a setting in which Guston was proud to appear distastefully incomprehensible.

Storr’s book shares just one shortcoming with other studies of the artist: he never tells us how to distinguish failed late Gustons from the artistically successful ones. But far from giving the impression of trying to have the last word, Storr leaves the reader wishing to sit down with him and talk more about the art.

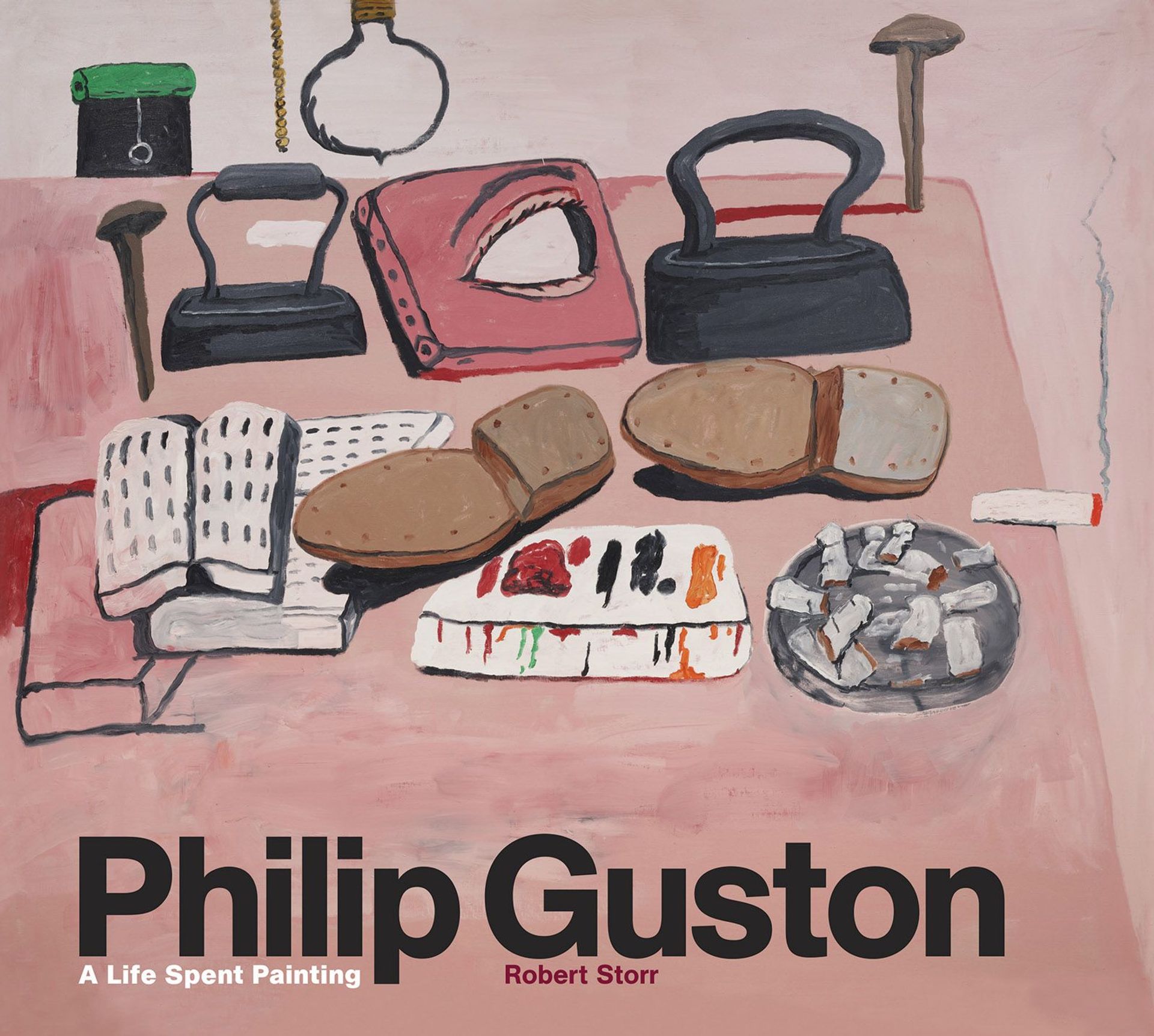

Philip Guston: a Life Spent Painting

• Philip Guston: a Life Spent Painting, Robert Storr, Laurence King, 348pp, £60 (hb)

• For an exclusive extract from the book, see Philip Guston’s fascination with the ‘funnies’ was key to developing his distinctive later style

• Kenneth Baker retired in 2015 after 30 years as the art critic of The San Francisco Chronicle. He is the author of Minimalism: Art of Circumstance (1989, 1997) and The Lightning Field (2009)