It was a hard act to follow. After Sotheby’s slick £150m Rembrandt to Richter multi-camera livestream auction the previous evening, Christie’s rounded off London’s Covid-restricted art market season on Wednesday night with a more traditional evening sale of high-end pictures and objects.

Christie’s less catchily titled Classic Art Evening Sale: Antiquity to 20th Century was, like Sotheby’s offering, a “cross category” selection that was, technically, a live auction. But only about 20 socially distanced individuals could attend in the saleroom, leaving the rest of the world to watch on a Christie’s website that at a time of accelerated digitalisation is beginning to show its age.

The major auction houses had cancelled their regular June and July evening sales in London. Christie’s chose to include the pick of its Modern and contemporary consignments in its ambitious new four-venue One auction, leaving the company’s Old Master, silver, decorative arts, prints and book specialists to cobble together the best of the pre-20th century rest for this catch-all evening event.

“Christie’s put everything into the One sale,” says Todd Levin, an art adviser based in New York, who buys both contemporary and period pieces for clients. “They were out of gas.”

But having built relationships with collectors for more than 250 years, Christie’s is always capable of pulling something exceptional out of its hat.

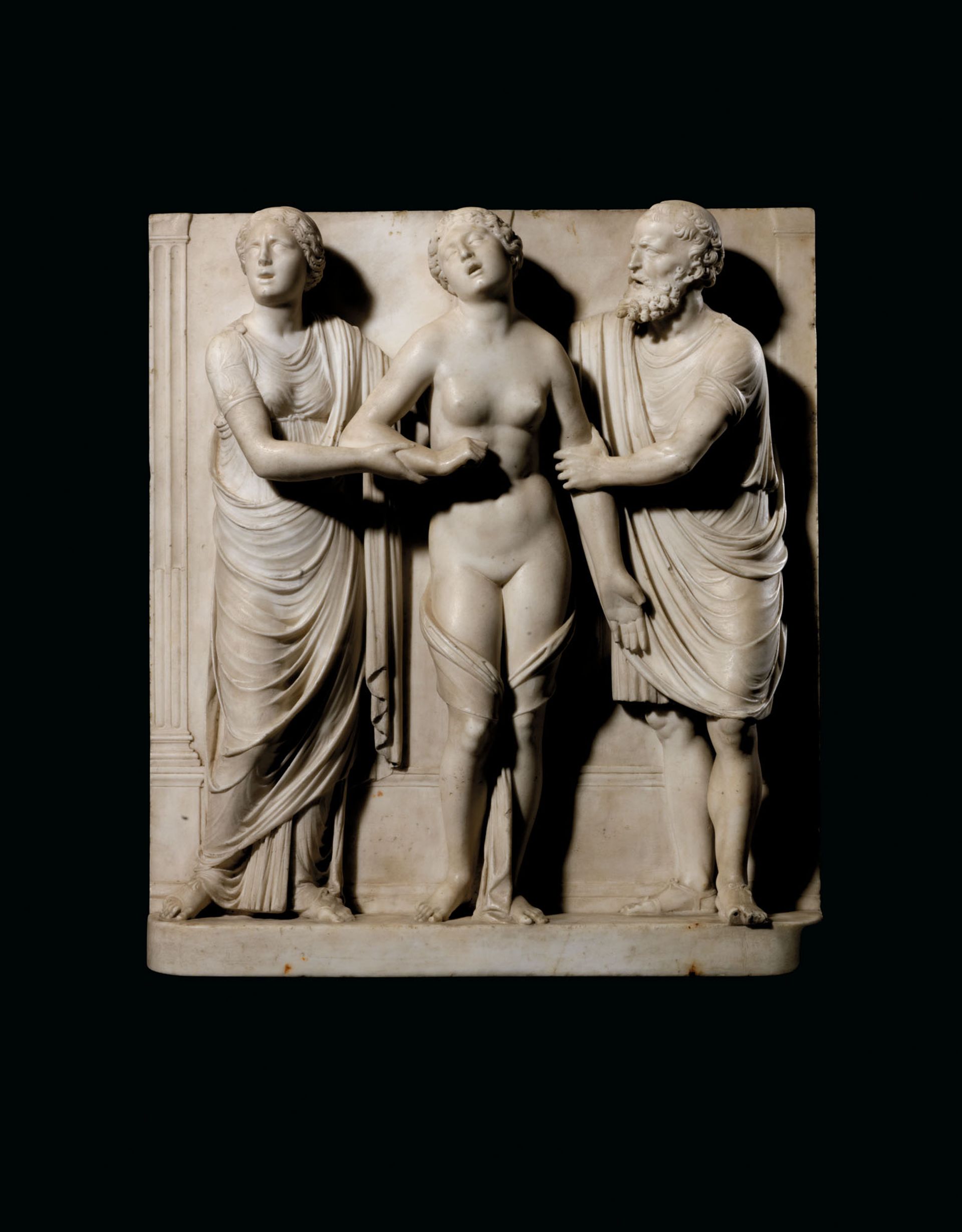

Death of Lucretia (around 1510), attributed to Antonio Lombardo © Christie's

The most magical piece in this sale was probably a superb 16th century marble relief of the Death of Lucretia, thought to be by Antonio Lombardo, a leading member of the family of artists who introduced classical sculpture in Venice during the renaissance.

Freshly discovered in a European private collection and estimated at £500,000-£800,000, the hitherto-unknown relief was thought to have been from a series of sculptures of classical heroines made in about 1510 for the Duke of Ferrara, for whom Antonio Lombardo worked as court sculptor for about a decade. The last Lombardo piece to feature on the open market was a spectacular relief of Dido, Queen of Carthage, discovered back in 1988 by the Dorset-based auctioneers Duke’s, who sold it for a record £275,000.

“Everything about it was great,” says Stuart Lochhead, a London-based sculpture dealer, of the Christie’s Lombardo. “You never see these things come on the market. The faces had a lot of emotion and it was in amazing condition. It was from the top level of that world,” adds Lochhead, who was one the socially distanced attendees in the saleroom.

The sculpture drew serious interest from at least four bidders before it was eventually knocked down to a private client on a telephone for £3.7m with fees.

Rubens’s Portrait of a young woman, half-length, holding a chain (1603-1606), painted when the young artist was either in Italy or Spain, was also billed by Christie’s as a “discovery,” but had recently been shown on long-term loan at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. At £4m to £6m, this was the most highly valued lot in the sale. For all the painting’s technical brilliance, it remained, like much of Rubens’s output, not a particularly appealing image to 21st century eyes and sold to a telephone bidder for a low estimate £4m (with fees), albeit the top price of the sale.

Rubens's Portrait of a young woman, half-length, holding a chain, sold for £4m with fees © Christie's

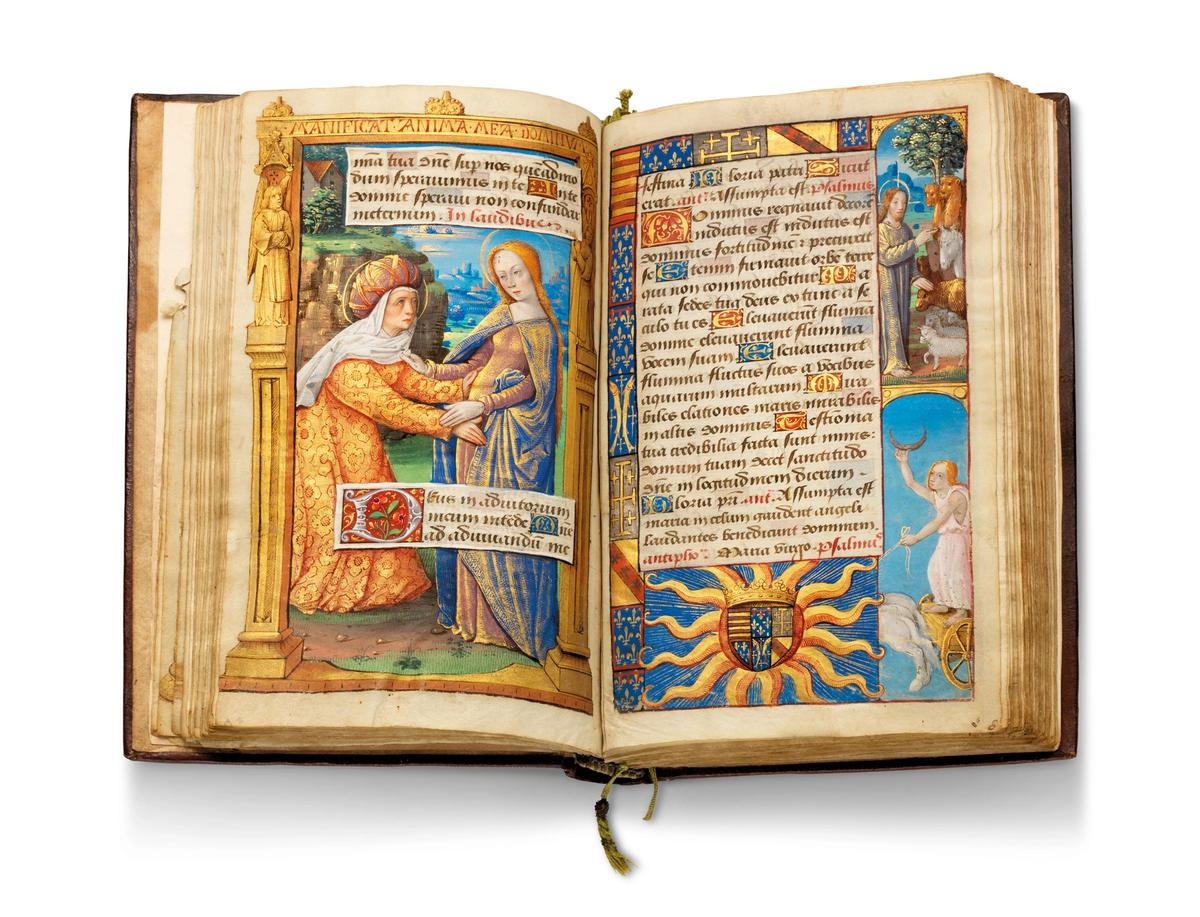

Bidders proved to be rather more excited about a sumptuously illuminated Book of Hours by the Master of the Monypenny Breviary, active in Bourges during the 1490s. Medieval illumination has, in relative terms, been one of the most underpriced areas of the art market for some time. But it burst into life here, with multiple bidders pushing this important prayer book to £1.6m (with fees), more than three times the upper estimate. It was the first time a Western illuminated manuscript had sold for more than £1m since 2015, according to Christie’s.

A similarly dated and similarly fine Burgundian School portrait on panel of an unidentified man holding a prayer book also impressed. Owned in the 18th century by Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s first prime minister, and now being sold by the Earl of Derby, this was in remarkable condition and was bought by a telephone bidder for £1.6m (with fees) against an estimate of £400,000-£600,000.

But there were also casualties. An impressive-looking ancient Egyptian mummy mask, estimated at £700,000 to £900,000, was one of 17 of the 65 offered lots that failed to sell.

“We’re at the end of July. A bit of fatigue has set in,” Levin says. “With online sales, there are auctions happening 24 hours a day. There’s an overload. It’s supposed to be great because you can do it in your jammies, but nobody’s seeing the art in real life.”

This appears to be more of an issue with pre-20th century art. Christie’s auction raised £21.2m with fees, a fraction of what Sotheby’s futuristic Rembrandt to Richter sale achieved the previous evening.

Admittedly Christie’s couldn’t bump up its total with a Miro or a Banksy. But the fact cannot be escaped that with its plush printed catalogue, old-school, connoisseurial mix of master paintings and antiques, and with auctioneer, Jussi Pylkkänen, theatrically wielding his gavel in front of a single online camera, this did feel like a sale from another century.