There were moments while watching Christie’s four hour live-streamed One sale when it was easy to become distracted by some paint drying on the wall—try as they might, this new generation of so-called "TV auctions" for our socially distanced age struggle to convey the excitement and urgency of a real-life salesroom.

The much-anticipated global relay sale of 80 lots of Impressionist, Modern, post-war and contemporary art and design totalled $361.6m ($420.9m with fees), against a low estimate of $337m, with 94% sold by lot, 97% by value—a pretty impressive result. The sale was well strapped-up with guarantees beforehand—an enormous 38 of the 80 lots were covered by a guarantee, and all but two of them were backed by third parties. Therefore, from our calculations based on low estimates, over $230m worth of the sale was essentially pre-sold. (Christie’s declines to confirm any figures relating to guarantees).

The format was an ambitious experiment—four auctioneers in Hong Kong, Paris, London and New York took it in turns to handle a portion of the sale, but all remained on the rostrum throughout the entire event, each fielding bids from the phone banks and a smattering of bidders in the room in their respective salerooms. Furthermore, each portion of the sale was held in a difference currency—Hong Kong dollars, euros, pounds sterling and US dollars. Still following?

One was intended to illustrate the global and democratic nature of the Christie’s operation and was a considerable feat to pull off. It also showed, four hours later, that democracy can be time consuming and less is often more. But, when asked in the post-sale press conference if the format would be repeated, Christie’s president and principal auctioneer for the London section Jussi Pylkkänen said: “For us it was an opportunity to invent a new language of auctioneering… I’m looking forward to when we can have full salerooms across the globe with auctioneers linked up and taking bids, with perhaps 50 carefully selected lots. Because I think we could achieve stupendous results.”

The sale started 45 minutes late, a reflection, says Christie’s technology chief Erik Jansson, not of a technical glitch (as was suspected by some) but of “Christie’s Live [bidding platform] doing what it was meant to do”—there were too many viewers, with more than 20,000 watching the sale, according to Christie’s chief executive chief executive Guillaume Cerutti.

And when the sale did start, the buyer breakdown split fairly evenly with 37% of lots going to the US, 38% to Europe, the Middle East, Russia and India and 26% to Asia.

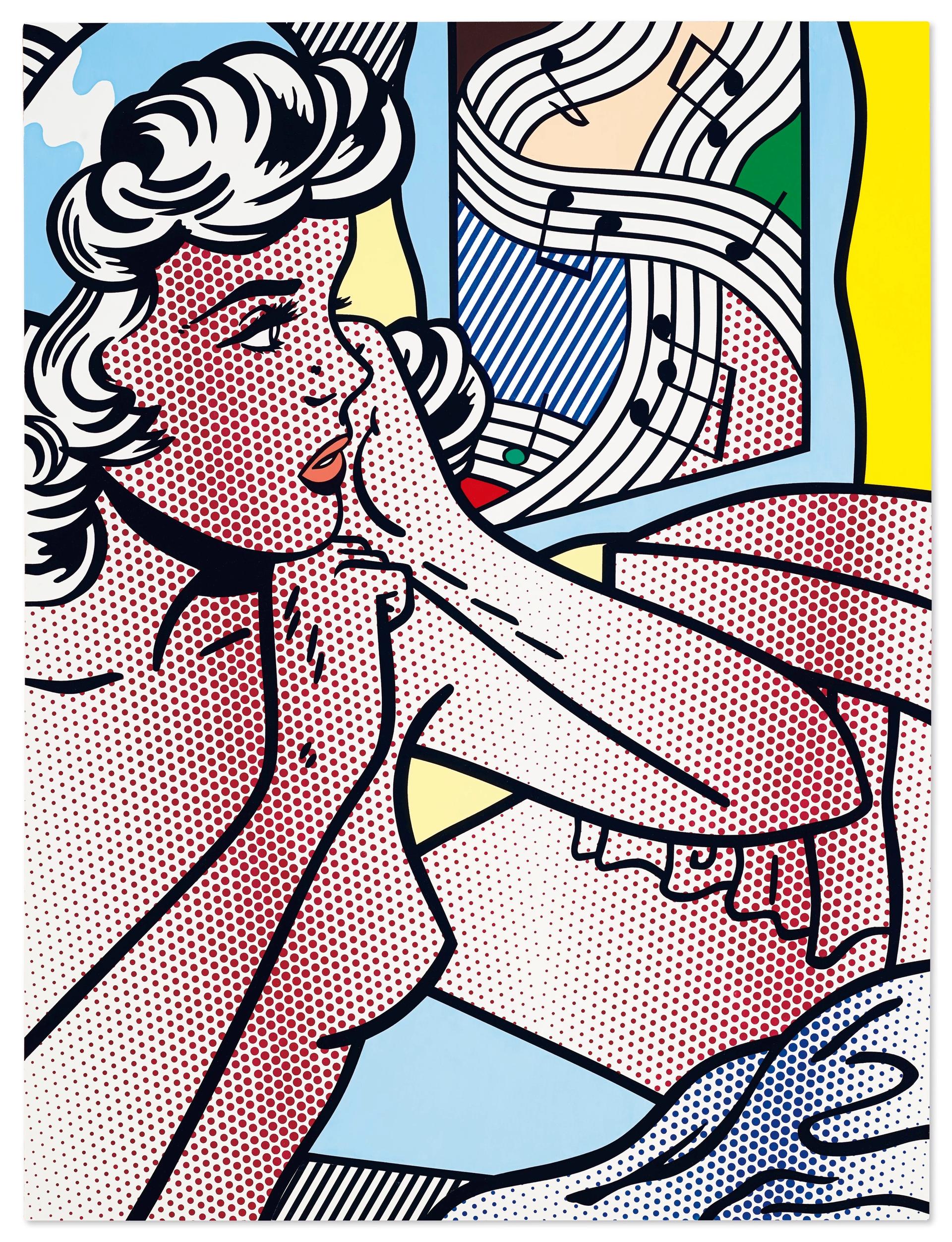

Roy Lichtenstein's Nude with Joyous Painting, (1994), sold for $46,242,500 at Christie’s One sale

The top lot of the sale was testament to the fact that Pop Art featuring naked women still sells—namely Roy Lichtenstein’s Nude with Joyous Painting, which was estimated in excess of $30m and guaranteed by a third party. After lengthy, creeping bidding, it sold for $40.5m ($46.2m with fees) in the New York section of the sale.

In joint second place were Barnett Newman’s Onement V and Brice Marden’s Complements, both of which sold just below their low estimates at $27m ($30.9m with fees), the Marden presumably to its third party guarantor. The Marden also set a new artist record. Just behind was Picasso’s Les femmes d'Alger, again guaranteed with an estimate in excess of $25m, which went for $25.5m ($29.2m with fees).

The major failure was in the opening Hong Kong segment, with a painfully long virtual silence as the sale’s cover lot, Zao Wou-Ki’s gestural abstract 21.10.63, failed to sell with an estimate in excess of $10m (one of the few big lots not shored-up by a guarantee). Christie’s also took a hit on one of the two house guarantees when a Philip Guston work failed to sell against hopes of $4m-$6m.

Pablo Picasso's Les femmes d’Alger (version ‘F’) (1955) sold for $29,217,500

The sale set a cluster of new artist records, some of them forgone conclusions due to guarantees. In the Hong Kong section, the Japanese painter Takeo Yamaguchi’s abstract Yellow Quadrangle went for HK$12.5m (HK$15.1m/US$1.9m with fees) and George Condo’s Force Field sold at HK$45m (HK$53.1m/US$6.9m). In London, the Spanish artist Manolo Millares’s oil and string on burlap work Cuadro 54 went for a record £900,000 (£1m/$1.3m with fees) while the British painter Cecily Brown’s febrile canvas Carnival and Lent went for an almost record £4.1m ($6.1m/£4.8m with fees).

Three other records were set for American artists in the New York chapter—for Ruth Asawa, whose delicate hanging sculpture went for $4.5m ($5.3m with fees), for Wayne Thiebaud, when his much-hyped Four Pinball Machines sold for $17.5m ($19.1m with fees), and—refreshingly—for a photographer, as Richard Avedon’s well-known image of Dovima with Elephants, Evening Dress by Dior, Cirque d'Hiver, Paris (1955) went for $1.5m ($1.8m with fees).

Christie’s sale inevitably drew comparisons with Sotheby’s first livestreamed evening auction on 29 June, which totalled $363.2m with fees, lower than Christie’s, which was topped by a triptych by Francis Bacon that alone sold for $84.5m (with fees). Sotheby’s chose to just have one auctioneer on the rostrum, Oliver Barker in London, fielding bids from London, Hong Kong and New York, and while still not wildly exciting to watch, the overall effect was slicker and more high-tech, thanks in part perhaps to new owner Patrick Drahi’s media, TV and telecoms credentials.

“All the auction houses have risen to the challenge over the past 10 days, some more successfully than others,” says Ben Clark, the deputy chief executive of the art advisory Gurr Johns (and formerly Christie’s deputy chairman of Asia). “Overall, they show that the market is fundamentally still ruled by supply and demand, and all the auction houses have curated sales intelligently, sourcing works they knew they could sell but only if they were at the right price—there is still some price sensitivity.”