American and British cultural institutions are facing an almighty reckoning over their colonial histories and present-day stance on racism and bias. But is reform possible, or is a full reset needed?

In the weeks since George Floyd was murdered by US police in May, spurring a wave of Black Lives Matter protests around the world, hundreds of museums, galleries and other arts organisations have been accused of tokenism, hypocrisy and fake solidarity for sharing online statements and social media posts decrying discrimination and pledging greater diversity within their walls. It has been painfully difficult for organisations to get it right: to commit to meaningful and lasting change rather than just dabbling around the edges with well-meaning sentiment.

So why is the art world, as with so many other industries, getting it wrong? “People are just tired. It cannot be constantly about black people making the case for racism and structural discrimination in society,” says the British MP David Lammy, who was culture minister between 2005 and 2007 during which time the Mayor’s Commission on African and Asian Heritage was published.

“The time for review and reflection is past. All the evidence is there. This has got to be a moment that’s far more than taking the knee or saluting Black Lives Matter. It’s now time for majority communities to act.”

Open letter season

In the US, major institutions are facing very public crises of confidence. There have been high-profile resignations—Jill Snyder stepped down as the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, after 23 years, for cancelling an exhibition by the American artist Shaun Leonardo examining police killings of black and Latino boys and men. Meanwhile, Nancy Spector, the chief curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, has taken three months’ leave following allegations of racism at the institution. The charges were outlined in a letter sent by curators on 22 June to the leaders at the Guggenheim, urging them to fix a working environment that “enables racism [and] white supremacy”. Its director Richard Armstrong says he is now “looking closely at our overall organisational culture and, crucially, how we will rebuild the trust of our staff”.

Much of their letter focused on the handling of the writer and art historian Chaédria LaBouvier’s employment as the curator of a Jean-Michel Basquiat show last year. During her tenure, LaBouvier repeatedly accused the museum of refusing to acknowledge her as the first black curator in its 80-year history. She also publicly called out Spector for excluding her from a panel discussion on Basquiat. Staff are now requesting an independent investigation; the Guggenheim declined to comment on the matter.

Similar language was evoked in an open letter sent by a coalition of current and former employees to New York’s cultural institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art on 20 June. That missive makes a number of demands including the immediate removal of “ineffective, biased” leaders, using recruitment agencies proven to hire black members of staff and the review of works thought to have been stolen from black and Indigenous communities. Further letters have since been addressed to the Met, the New Orleans Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts, among others.

The collective open letter format has become a museum call-out keystone in recent weeks precisely because these institutions have long silenced such conversations internally, in part due to a lack of black members of staff. “For over two centuries the traditional art-historical narrative in this country has remained predominantly Eurocentric and male in nearly every major museum. It follows that only 4% of the positions outside service and security in US art museums are held by black professionals,” writes Dr. Kelli Morgan, the associate curator of American art at the Indianapolis Museum of Art Galleries at Newfields, in an essay for Burnaway magazine. “What we do not speak honestly enough about are the very distinct ways in which racism and sexism are utilised to traumatise us and oftentimes undermine our work—the very work that our respective institutions claim they want—and often recruit us to do.”

Few public missives have been sent to British museums. But, according to the Victoria & Albert Museum’s director Tristram Hunt, “there is a huge amount of disquiet and frustration and also energy for reform” both among staff and among the artists and makers the V&A works with. “They want a stronger steer right across the organisation of us being an anti-racist institution,” he says. “We have to work much harder in terms of recruitment, in terms of anti-bias training, in terms of supporting diversity at board level, in terms of being more conscious as an anti-racist organisation.”

“Give back the swag”

So what about restitution—a topic that gets right to the heart of the colonial bedrock of encyclopaedic museums? The British Museum was denounced by thousands on Twitter as an imperial institution cynically engaged in a marketing ploy and was exhorted to “give back the swag” after its director Hartwig Fischer posted a statement saying the museum is “aligned with the spirit and soul of Black Lives Matter everywhere”.

In their statements, neither Fischer nor Hunt made reference to restitution—both have previously said they are bound by onerous laws that prevent national museums from deaccessioning works. Hunt, a former politician himself, says he would gladly reconsider the V&A’s position if the law changed, but he is doubtful of the political will.

“[The legislation] needs to go through both houses and would consume a lot of political time,” he says, adding that “the V&A will seek to be as active as we can under the current framework”. The museum is currently subject to one official restitution claim involving the Maqdala treasures, looted from Ethiopia in 1868.

Whereas Hunt believes France will take direct action following the 2017 Sarr-Savoy report on African art restitution by building museums in Francophone countries where they will lend national collections, the British approach will be more focused on developing “richer bilateral relationships and active programmes of exchange and display”. Recognising the V&A as born of the imperial moment, Hunt also advocates for displays that highlight the complex, layered meanings of objects.

“I have been adamant we should be totally transparent about our colonial past,” he says. “In that sense, you can’t decolonise the V&A because colonialism is so embedded within the history of the organisation.”

Symbolism or substance?

It is a different matter on the streets, however. In cities throughout the US and UK, decolonisation of a more radical nature has been taking place—dozens of Confederate and imperialist statues have been felled, beheaded and sprayed with graffiti. Others have been peacefully removed. Most recently, the American Museum of Natural History in New York agreed to evict from its steps an equestrian monument of Theodore Roosevelt flanked by a Native American and black man. At Oxford University’s Oriel College, the British imperialist Cecil Rhodes will, at last, be taken down.

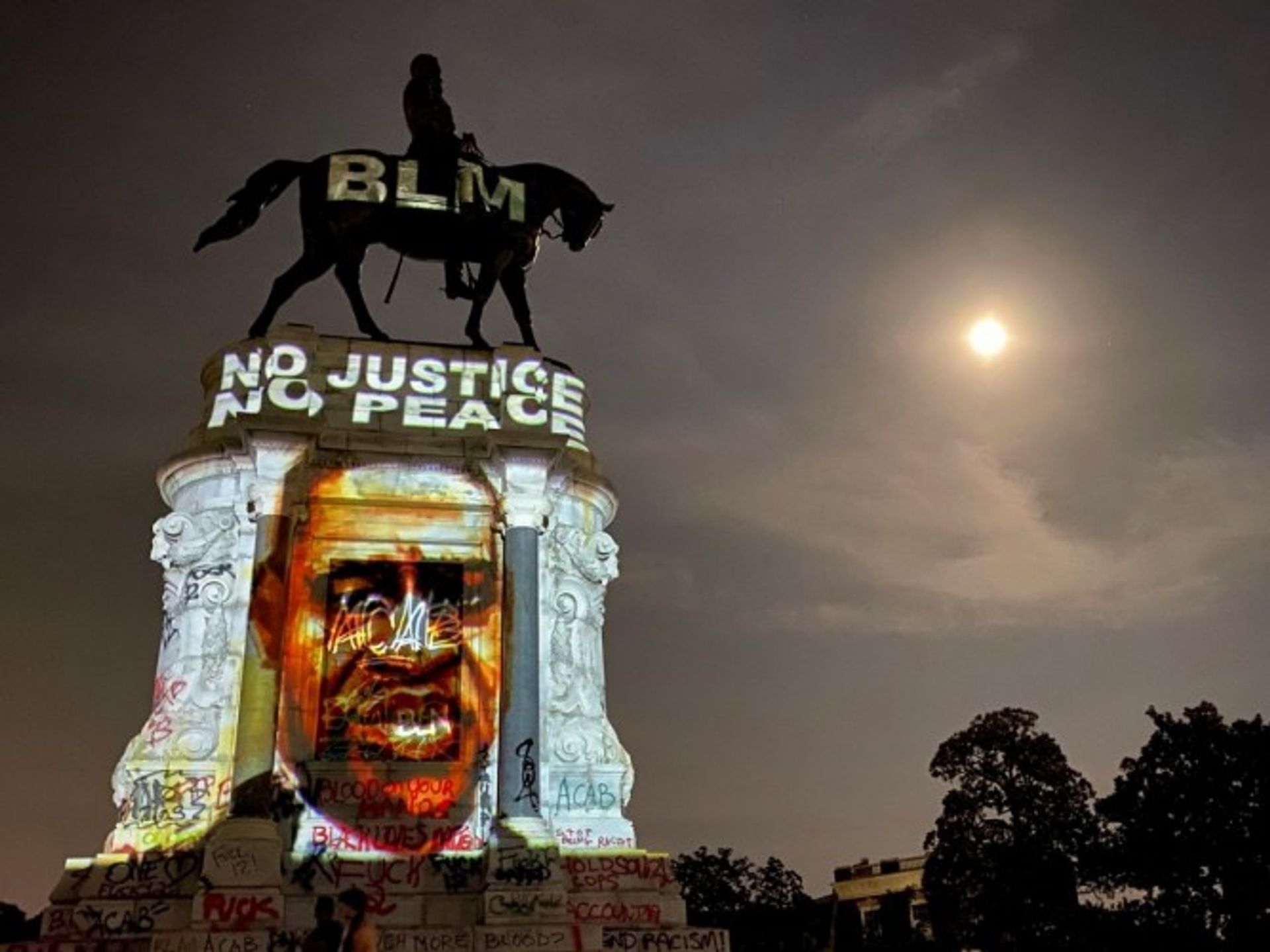

A Black Lives Matter tribute to the late George Floyd is projected onto the gratified statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia. Photo by Wendy Goodman Humble/VPM News

In Bristol, southwest England, a statue of the 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston was torn down and dumped in the harbour by protestors after decades of democratic attempts to have it removed. Colston, who made his fortune with the Royal African Company, overseeing the enslavement of an estimated 84,000 Africans, 19,000 of whom died in the most inhumane conditions on board slave ships, may now be destined for a Bristol city museum, displayed alongside Black Lives Matter placards. Lammy believes this should have happened “years ago”.

He says: “This story has been in the underbelly of that city for several decades. It’s the role of museums to put these things in context and to help communities have that debate, not to hold up these statues as hallowed individuals, when they were responsible for serious murder.”

But, as Lammy notes, while the statue debate “is emblematic” it would be “missing the point of the substance of all of this if we just focus on the symbolism”. Though, speaking on a Zoom with the British artist John Akomfrah last month, the American writer and academic Saidiya Hartman says that the “targeting and destroying” of police stations as well as statues “has been critically important in animating the energy of movements”. She adds: “It’s not just about a desire for police reform, it’s about a desire to dismantle the very apparatus of western modernity, from the ideational processes to the material and social bedrock of a racist order.”

"Reform presents us with platitudes"Zarina Muhammad, White Pube

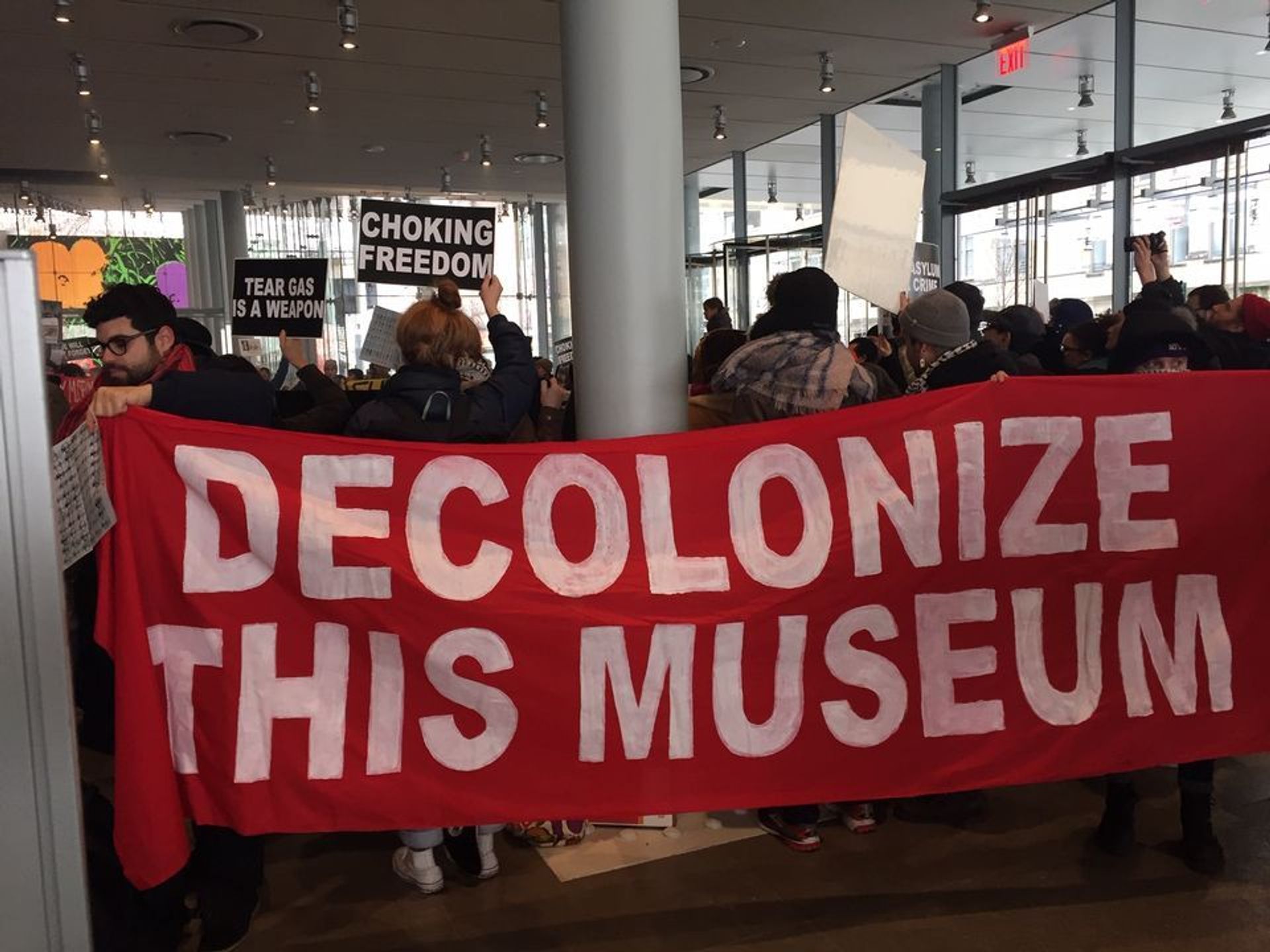

In terms of pragmatic action, museums in the city where Floyd was murdered including the Walker Art Centre and the Minneapolis Museum of Art have already ended contracts with the local police department, whom they employ as security for events. The New York activist group, Decolonize This Place, has a successful history campaigning against those who profit from the prison industry and police state. Last year, after sustained pressure from the group, Warren Kanders resigned from the board of the Whitney Museum of American Art over his firm Safariland’s use of tear gas on migrants at the US-Mexican border. It recently emerged that his chemical weapons were being used on protestors in Minneapolis, prompting Kanders to announce he is selling off his crowd-control products divisions.

Strength in numbers

Recognising what can be achieved in numbers, several new coalitions have sprung up in the past few weeks, including Art Workers for Black Lives, which advocates for police and prison abolition and slavery reparations. Patrick Jaojoco and Natalia Viera Salgado, the founders of the New York collective, say that defunding the police “is only one aspect of a larger movement for decolonisation, reparations and racial justice”. The group now boasts over 2,000 signatories and several other chapters have sprung up in cities including Boston and Philadelphia.

As with Kanders, change needs to start at very top, Jaojoco and Salgado say: “White supremacist structures are perpetuated by many of those leading and funding the art world. As arts workers, we need to identify with each other and stand up as a strong community of individuals rather than defer to a small number of institutional voices [to] apply pressure to city and state government to defund and abolish the police and invest in community arts, housing, health and other services.”

A protest against Warren Kanders led by Decolonize This Place at the Whitney Museum in New York last December. Nancy Kenney

The language—and politics—of abolition is creeping into the art world, too. Critics argue that diversity and inclusion policies only serve to deflect from the stagnation at the core of arts organisations. As the London-based writer and curator Zarina Muhammad writes on the White Pube website: “Reform presents us with platitudes, the sweet promise of action, of new people and faces, but it is fundamentally the same shape.”

The problem in the UK, according to the Karachi-born, London-based artist Rasheed Araeen, is that funding organisations such as Arts Council England champion diversity policies that encourage “divisions on the basis of ethnic differences”. Such policies, Araeen argues, “are smokescreens to hide [institutions’] inability or unwillingness to recognise the real issue—the whiteness of modernity enshrined in their colonial structures”. Araeen adds: “The Arts Council has spent millions and millions on grass-roots art organisations, not in support of art but in support of so-called cultural diversity.”

Whether reform is possible or abolition is the answer, all agree that the most significant shift now has to come from white-led cultural institutions. Hunt describes the task ahead as a “shared endeavour—that’s actually quite a big change for a lot of liberal thinkers”.

As Shaun Leonardo says: “White art institutions will never truly commit to the work, the necessary dialogue, if the individuals that make up these institutions and systems are not assessing and grappling with their own white identity. That is what is missing. Until white individuals move beyond addressing the murder of George Floyd and instead move to identify officer Derek Chauvin within themselves, their work will not bend toward anti-racism.”