The Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Centre Pompidou in Paris have each been presented with a major gift of works on paper from Giuseppe Penone, the Italian artist aligned with the Arte Povera movement who is perhaps best known for sculptures excavating the essence of trees.

The gift to the Philadelphia museum—309 works on paper and five artists’ books—spans five decades of his career beginning in the late 1960s and reflects his sweeping range of techniques, from frottage to graphite to India ink to watercolours. The donation makes the museum the most significant repository of Penone’s drawings in the US: it previously owned only two.

The artist is presenting some 350 drawings to the Pompidou that similarly embrace his entire career, in which he has delved into the connection between humans and nature by zeroing in on themes like breathing, growth and aging while using humble materials like stones, branches and leaves. The Pompidou previously had 51 works by Penone, 22 of them drawings.

In a phone interview from his home in Turin, the artist, 73, says he had kept most of the drawings he has made since the late 1960s and felt that establishing a repository in both Europe and the US would be ideal. His relationship with the Pompidou stretches back to its founding in the 1970s—“France is like my second nation,” Penone says—and was strengthened during his years teaching at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

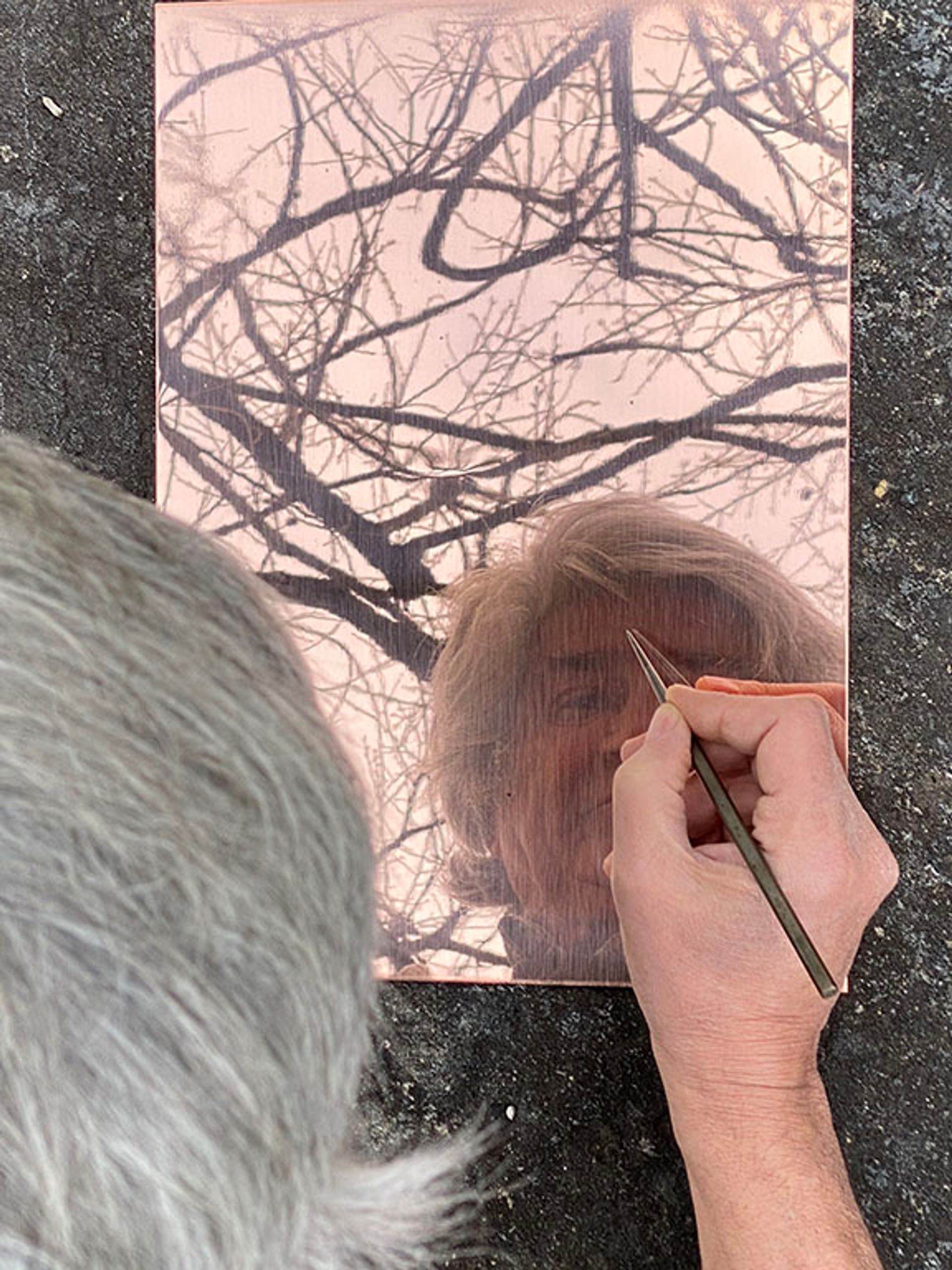

Giuseppe Penone working on an etching on a copper plate © Archivio Penone

Penone says he cemented a relationship with the Philadelphia Museum of Art while working with Carlos Basualdo, its senior curator of contemporary art, on The Inner Life of Forms, a book surveying his life’s work that was edited by Basualdo and published by Gagosian and Rizzoli in 2018. “It is a museum that has a deep relation with Europe,” he says.

“Every space has a kind of spirituality and identity,” the artist adds of the two art institutions. “I hope there will be a dialogue with the collection in each museum and between the two gifts.” Both institutions plan exhibitions of the works on paper in 2022.

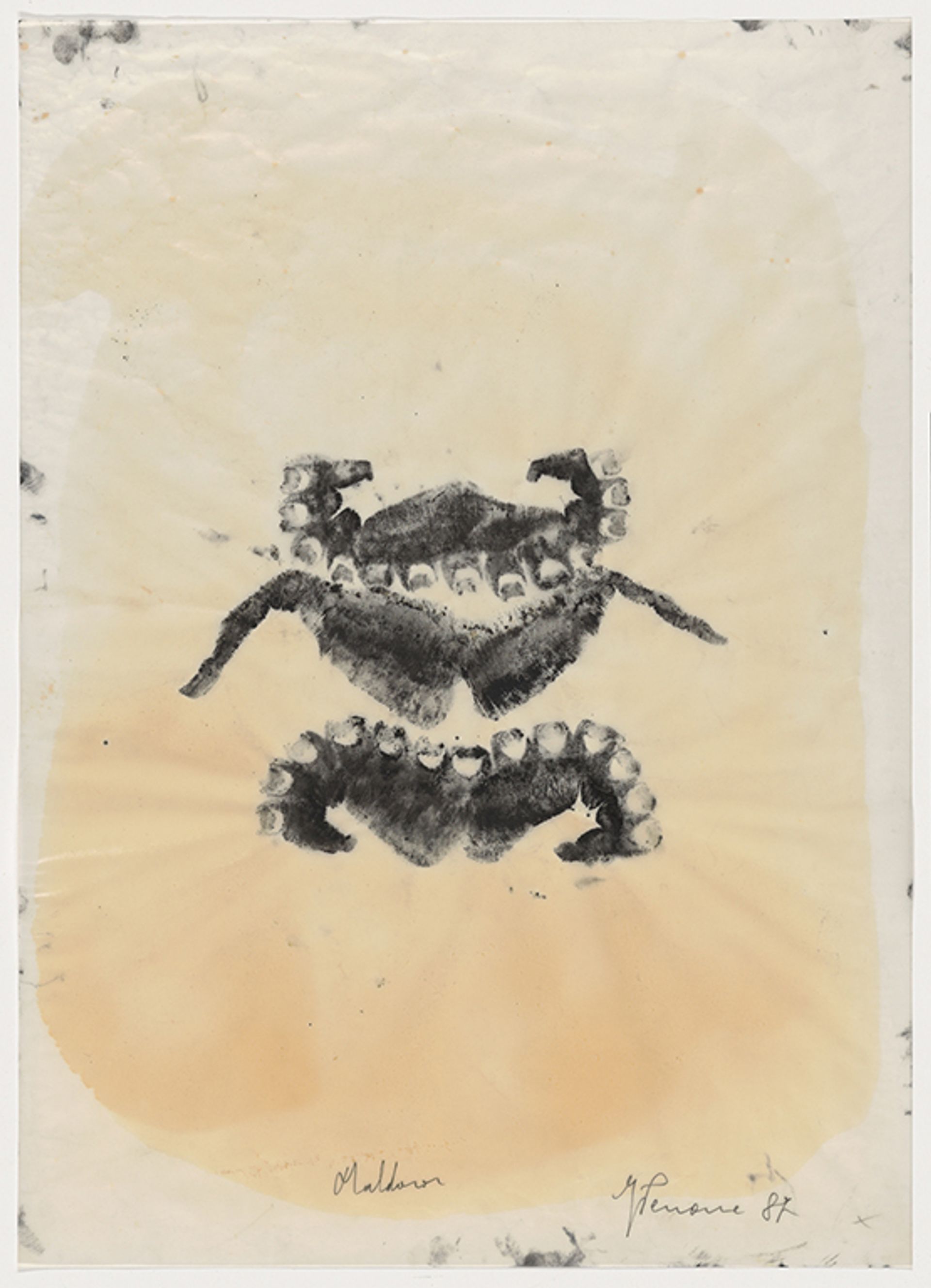

According to Basualdo, the highlights of the Philadelphia trove include some of the artist 's very first drawings, including works related to his celebrated Maritime Alps, a sculptural series staged outdoors in the late 1960s. The curator is also particularly fond of drawings from a series inspired by the 1869 French prose poem Les Chants de Maldoror in which Penone uses the imprints of his hands to create “a changing landscape of signs from which animal forms and intimations of monstrosity emerged almost magically”.

Giuseppe Penone, Maldoror (1987), black ink applied with the artist's hand on solvent-soaked translucent paper Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2020

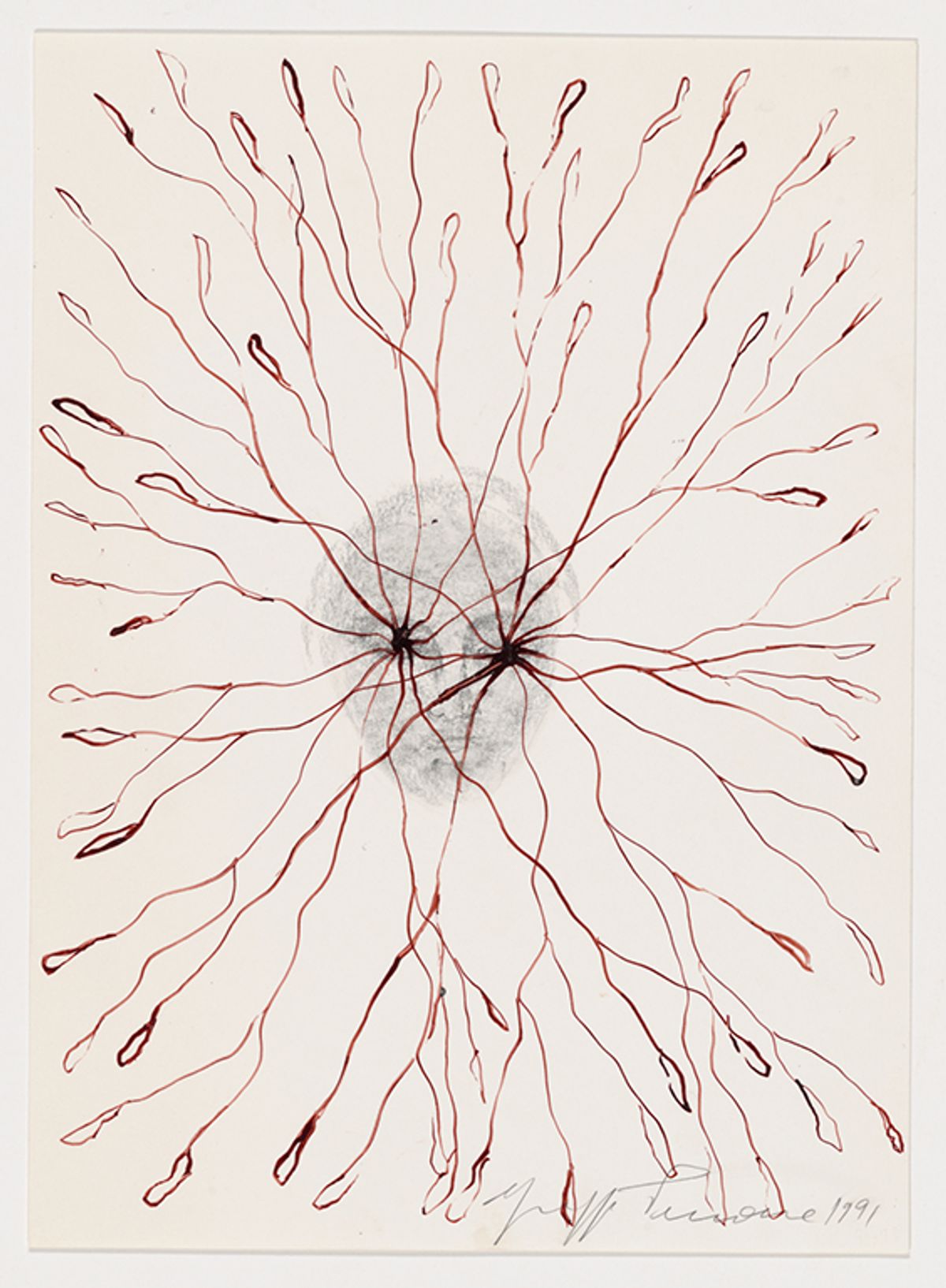

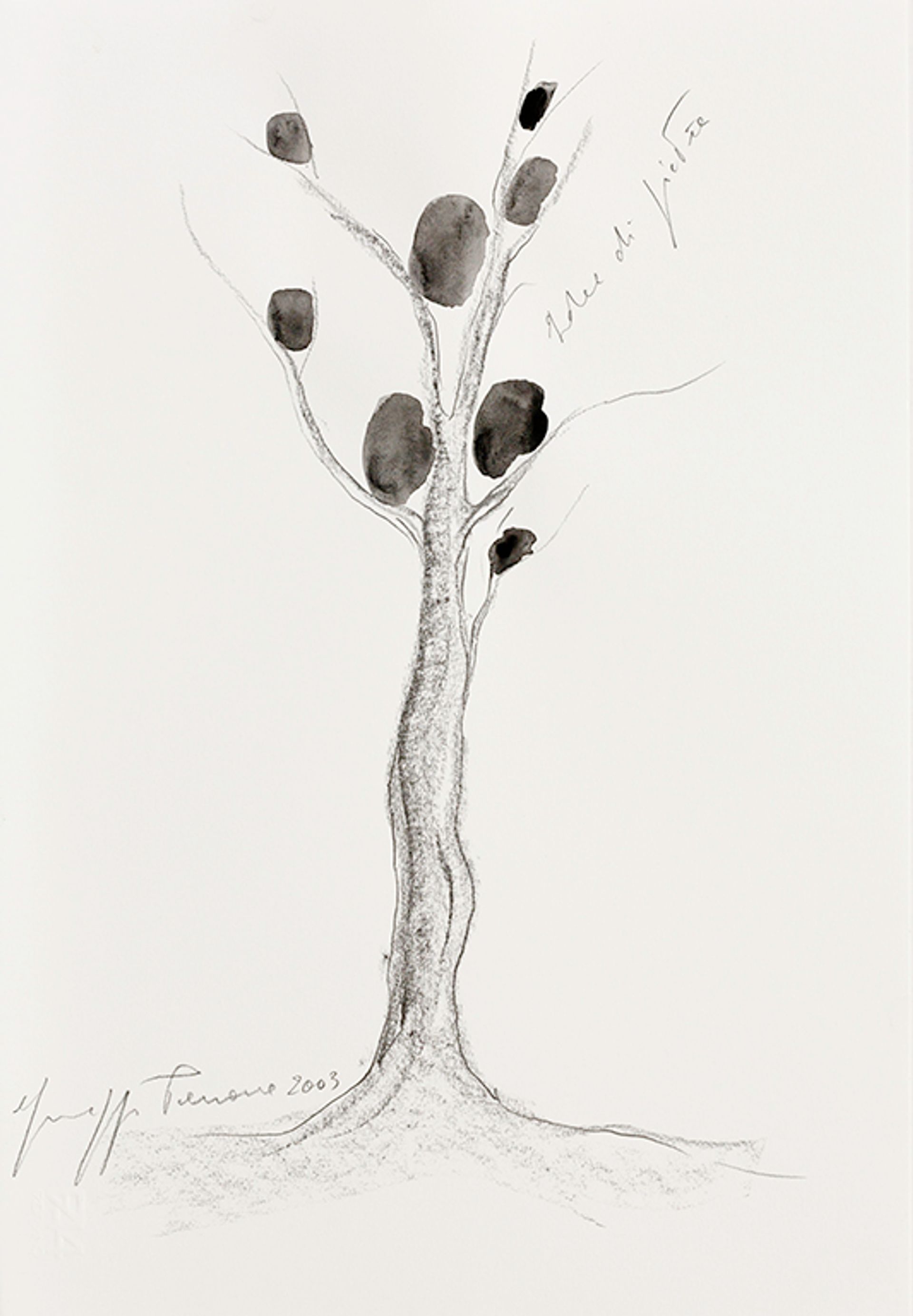

Basualdo also cited a number of drawings related to the artist’s Ideas of Stone, a series of monumental sculptures of bronze trees with large stones in their branches, and a group of drawings made between 1977 and 1980 for his poetic Breath series, molded forms in terra cotta that evoke myths about infusing humankind with the breath of life.

Giuseppe Penone, Ideas of Stone (2003), pencil, graphite and watercolour on paper © Archivio Penone

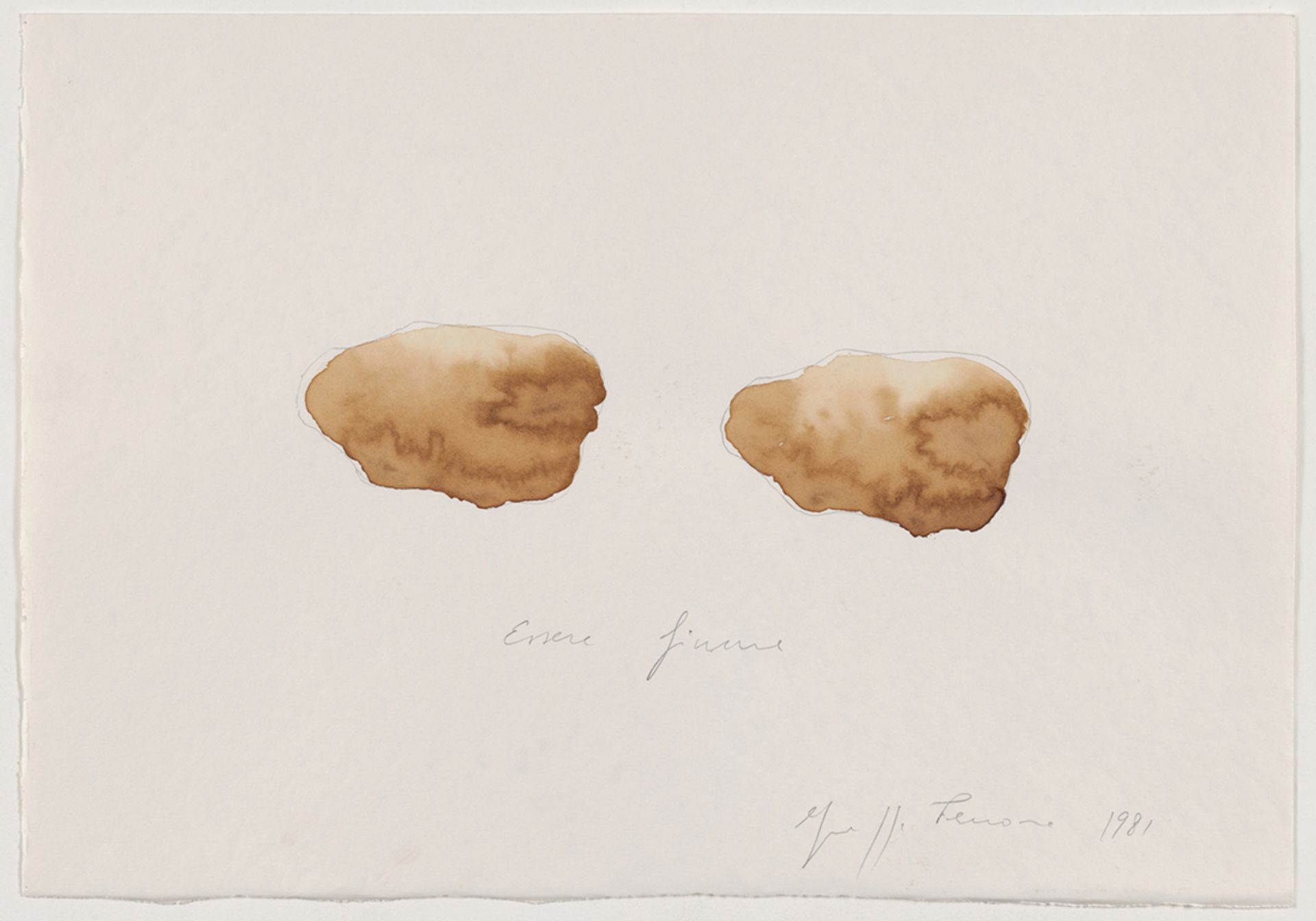

Another highlight is a group of works on paper related to To Be a River, in which Penone retrieved a stone from a river in his native Piedmont region and then sculpted another one from a quarry to exactly replicate the first one. Some of those works reproduce the two stones using different techniques (pencil and coffee on paper, watercolour and pencil on paper, pencil on paper and graphite on paper) while others simply spring from a similar inspiration.

Giuseppe Penone, To Be a River (1981), pencil and coffee on paper Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2020

“He thinks through drawing, there’s no doubt about it,” Basualdo says. ‘’The drawings are absolutely indispensable, a founding element in his work. He conjures a world of resonances between the animal kingdom and humans and the vegetal and nature in general.”

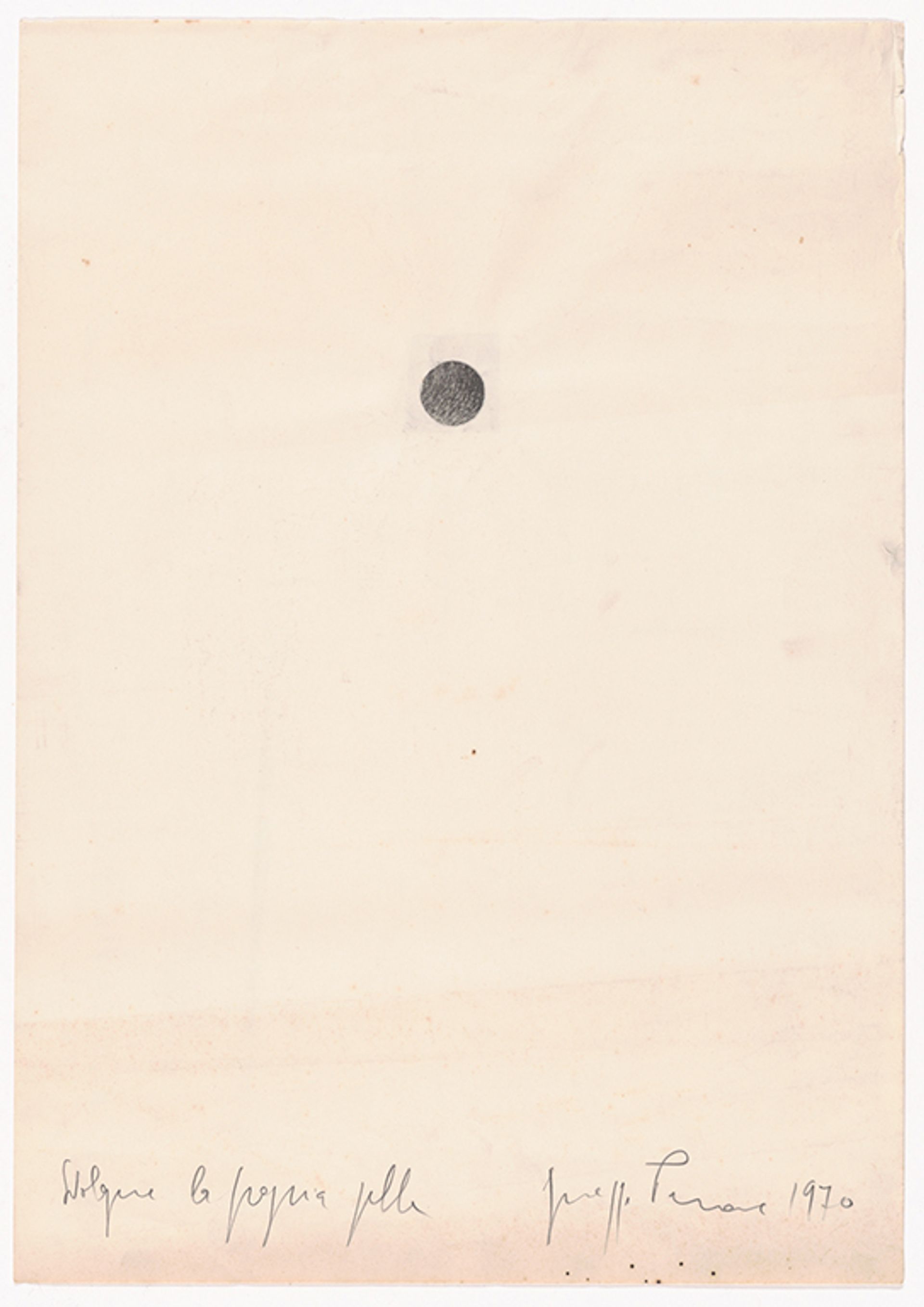

The curator also pointed to drawings related to Penone’s “To Unroll One’s Skin” from 1970-71, a series of works in which the artist draws a correspondence between the surfaces of human bodies and the surface of stone or marble. In those works, the artist captured the patterns of rock and bark, skin and hair, through frottage, or rubbings on sheets of paper, and well as by pressing his body into surfaces.

Giuseppe Penone, To Unroll One's Skin (1970), collage of graphite rubbing on wove paper adhered behind cut-out in wove paper Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2020

“Drawing is an unaltered means of expression, beyond the specificity of language—drawing is a language out of time,” Penone says. “From the ancient works found on the walls of caves, to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it transcends the culture and language of each era.”

“There’s a kind of freedom in the drawing that you cannot have in the [sculptural] work itself, a synthesis,” the artist adds. “And I can enrich the understanding of the work by writing down ideas,” from instructions to literary quotations, on the paper.

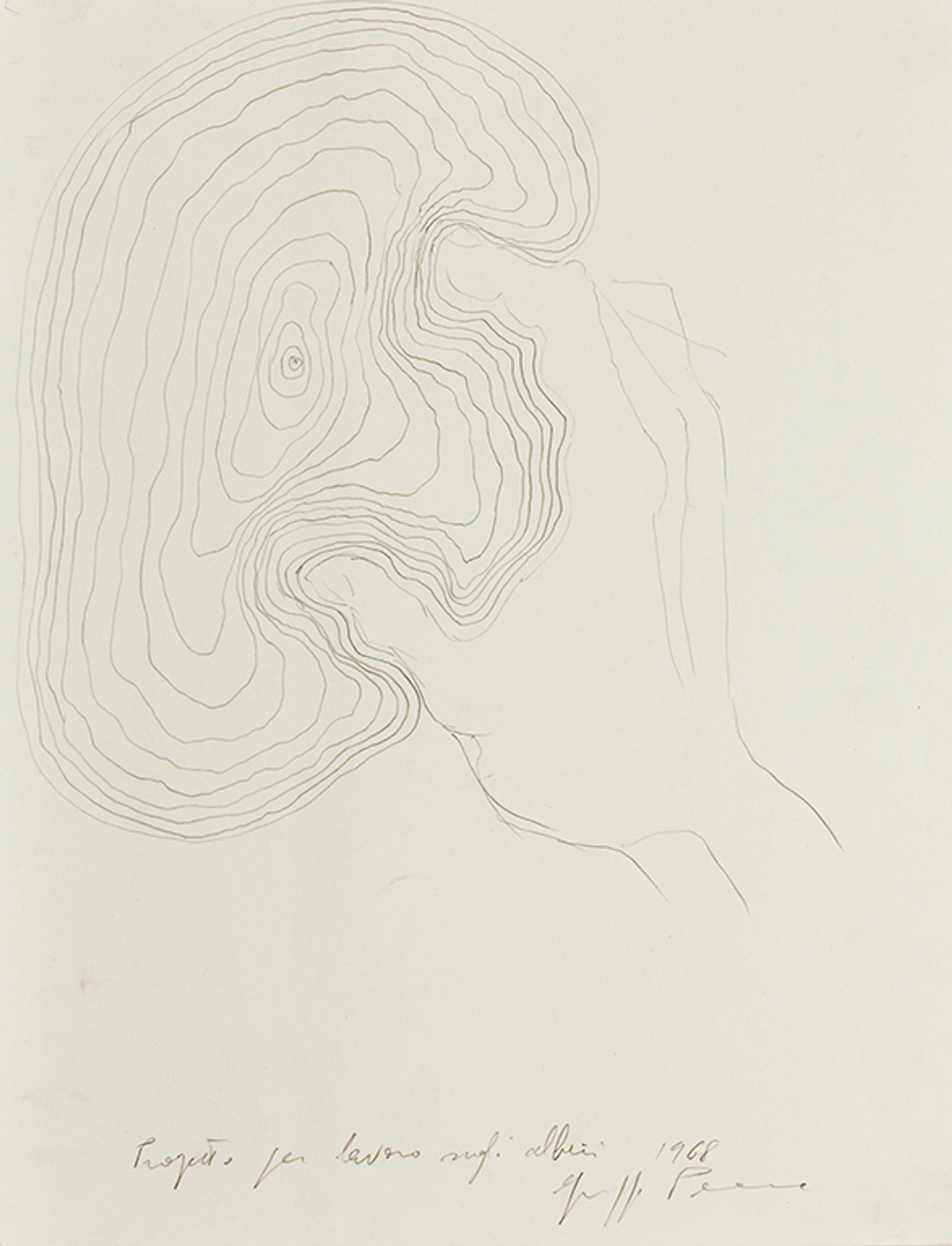

Among the most striking works donated to the Pompidou are three drawings related to Working Project on Trees (1968), dating from when Penone first launched his exploration of that subject, says Jonas Storsve, keeper of drawings and prints in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the museum. The works are linked to a sculptural piece in which a bronze cast of the artist’s hand is attached to a tree, illustrating the idea that, “It (the tree) continues to grow except at this spot.”

Giuseppe Penone, Working Project on Trees (1968), graphite on paper © Archivio Penone

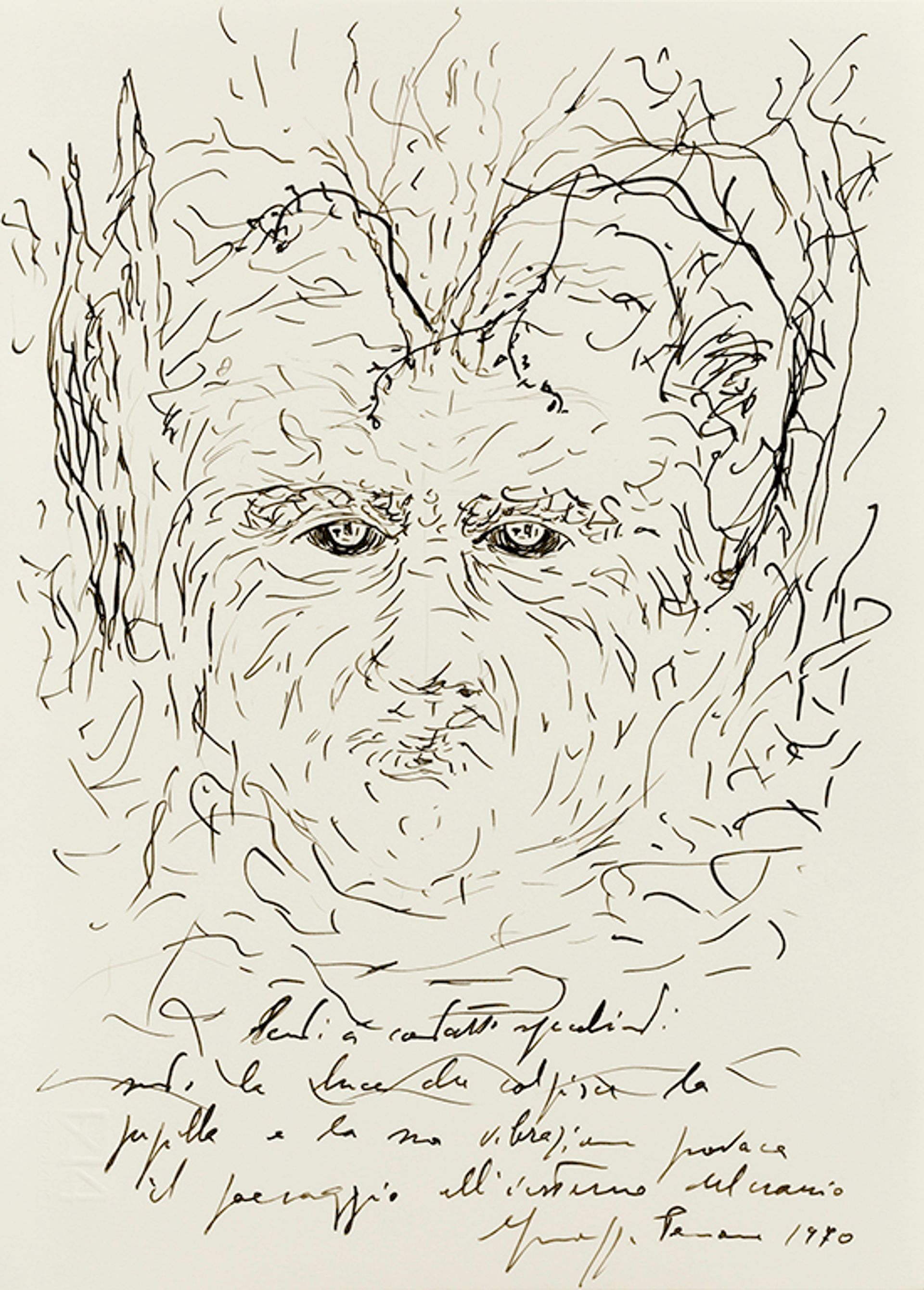

Storsve also cites Mirrored Contact Lenses (1970), an ink drawing based on a now-famous project in which Penone donned mirrored contact lenses that reflect the surrounding landscape but render the wearer blind.

Giuseppe Penone, Mirrored Contact Lenses (1970), India ink on paper © Archivio Penone

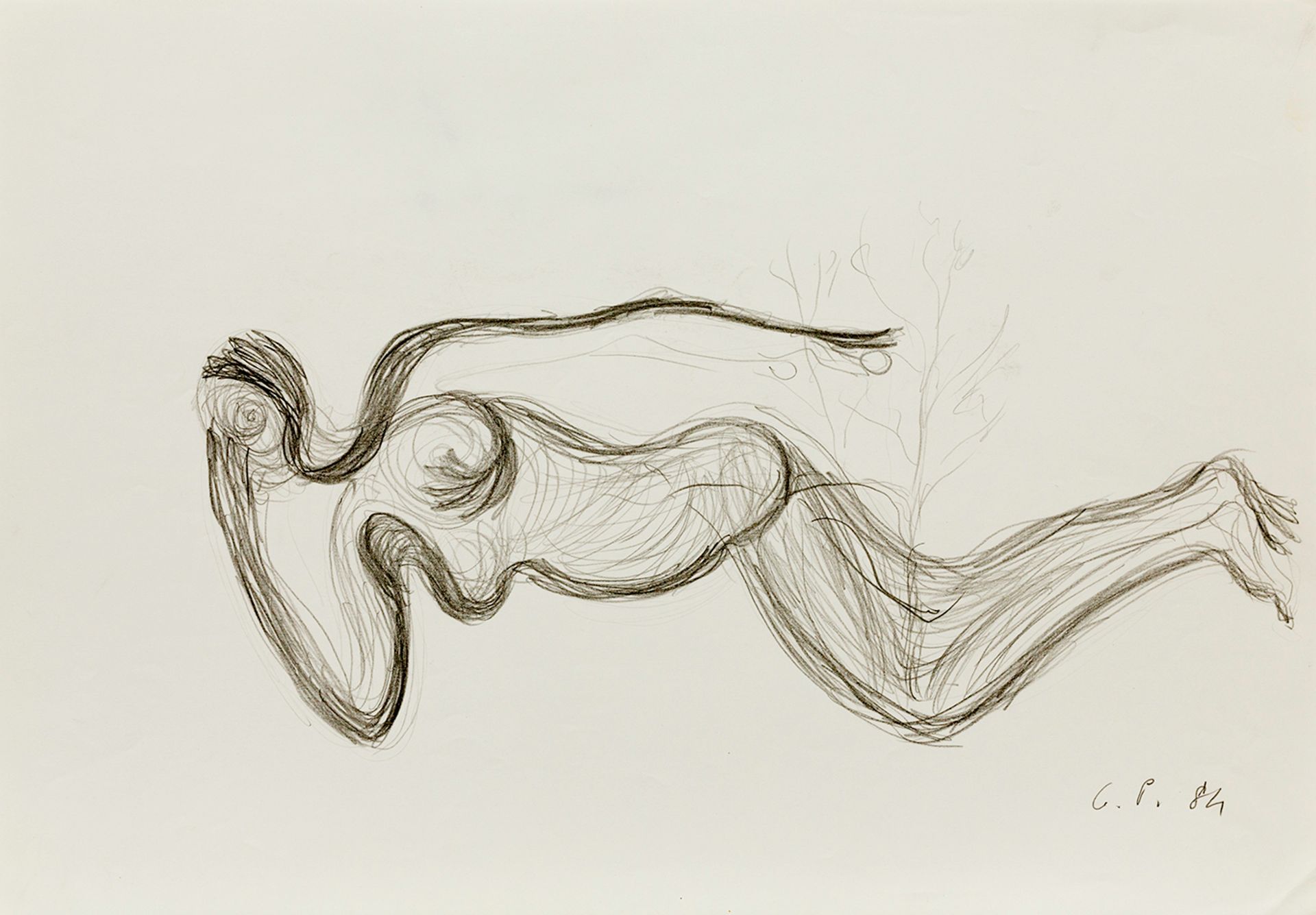

And he points to five untitled works in ink and graphite on paper linked to the artist’s so-called “vegetal gestures” in bronze, sculptures that he installed outdoors in connection with bushes or trees or indoors in connection with plants in pots. The drawings depict a reclining Eve based on a well-known French Romanesque statue, and “stress the importance of the serial aspect in Penone the draughtsman,” Storsve notes.

An untitled 1984 work by Giuseppe Penone in graphite on paper, evoking his "vegetal gestures" in bronze inspired by a French Romanesque sculpture of Eve made for the Cathedral of Autun © Archivio Penone

Penone says he wants the gifts to foster a sense of “participation and belonging” among museum visitors. “My hope is that the public will be able to feel and share this energy,” he says.