While closed by the UK’s Covid-19 lockdown, the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich has finalised the acquisition of 29 sculptures, drawings and prints by the British sculptor Elisabeth Frink, following the wishes of her son Lin Jammet. This “significant body of work” will enable the museum, which is part of the University of East Anglia, to become a permanent “study centre” for the artist, says its head of collections, Calvin Winner. The acquisition heralds a wave of works from the Frink estate that are being dispersed across public collections in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Together, the 29 works offer a “cross-section” of Frink’s artistic career, Winner says. Among them are the expressionistic early sculpture Vulture (around 1952), depictions of male figures inspired by the 1960s space race and lantern-jawed large heads from the “sinister” Goggle Heads series and more “philosophical” Tribute Heads. A selection of works on paper reveal Frink’s “great draughtsmanship”, he says, including three 1992 screenprints of the Green Man, the medieval symbol of rebirth, made “when she had been diagnosed with cancer but was still determined to work”.

Frink made Vulture (around 1952) as a young graduate of the Chelsea College of Arts Photo: Pete Huggins

Two “rather playful” long-legged bird forms in bronze, Mirage I and Mirage II (1969), which Frink identified with flamingos she saw in France’s Camargue region, are already on view beside the lake in the Sainsbury Centre’s 350-acre sculpture park. Although the museum is closed until at least 4 July under the UK government’s lockdown restrictions, the outdoor sculptures on the university campus are freely accessible to “the students that remain on site but also the local community” in times of social distancing, Winner says. A “focused display to celebrate the acquisition” is planned for the museum’s project space after reopening, he says.

All of the newly acquired works were previously shown in the Sainsbury Centre’s major 2018-19 exhibition, Elisabeth Frink: Humans and Other Animals, curated by Winner and Tania Moore. The largest show dedicated to Frink since her death in 1993, it focused on her preoccupation with the relationship between humans and animals, from her student days in the early 1950s to her final works.

Tribute Heads in the Sainsbury Centre's 2018-19 Frink exhibition, the largest show of her work in 25 years Photo: Andy Crouch

The aim was to “remind people that she was a major British artist of the second half of the 20th century who was slightly in danger of falling off the radar,” Winner says. Frink came to prominence as a young graduate of the Chelsea College of Art, with the Tate buying an early bird sculpture in 1953 and including her in its 1965 sculpture survey. But as Britain’s “New Generation” of geometric abstract sculpture gained currency in the 1960s, Frink’s figurative bronzes fell from favour.

Although the artist later achieved popular success with a host of public commissions, “she wasn’t getting the shows that her male counterparts were getting” and there was “a lack of critical writing about her work” during her lifetime, Winner says. The Sainsbury Centre exhibition sought to re-assess her reputation by exploring social and political “themes that perhaps she had been reticent to talk about personally”, he says. “Self-publicity wasn’t her style.”

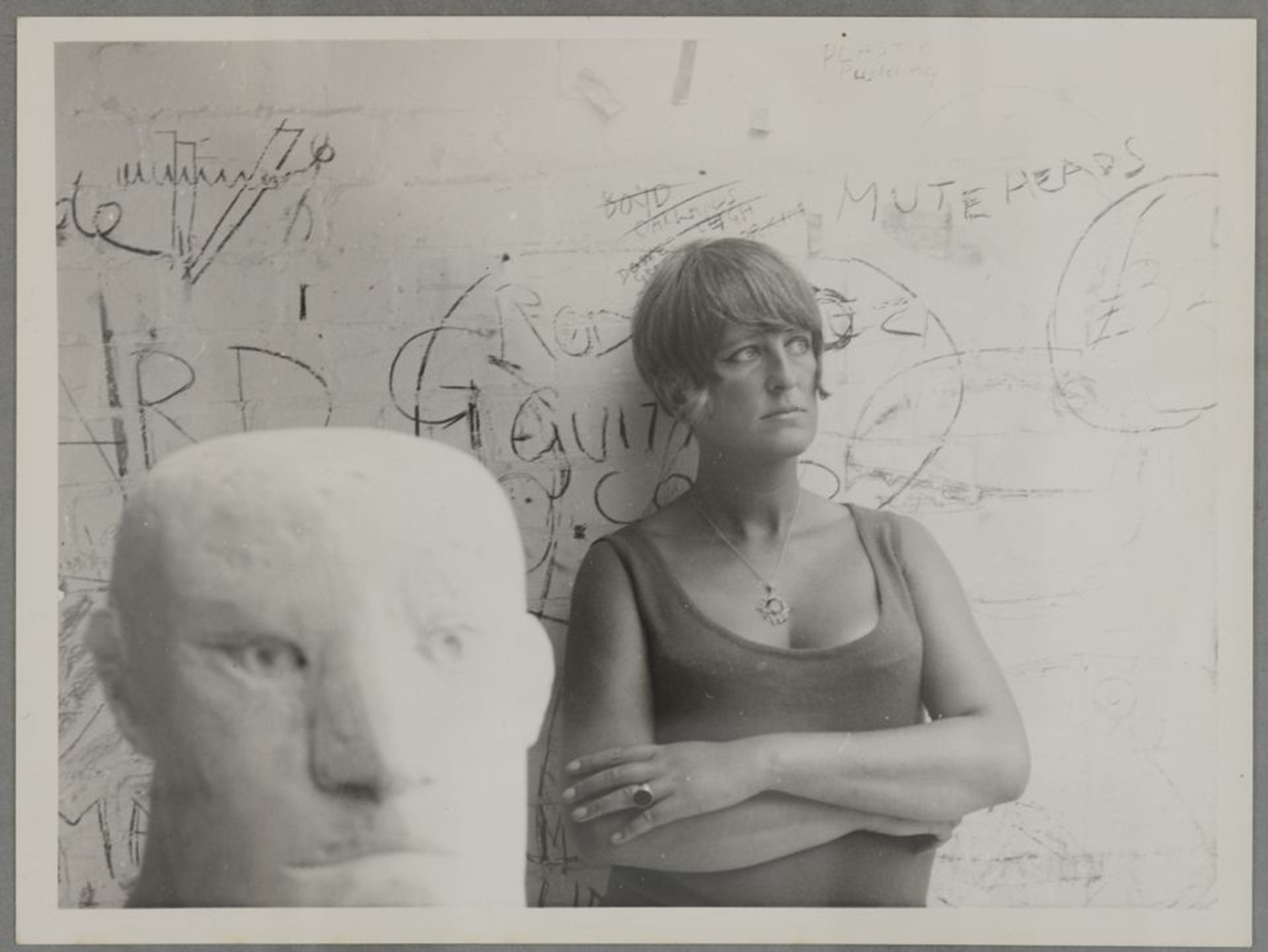

Frink photographed by Edward Pool (around 1964-65) © Frink Estate and Archive; Dorset History Centre

The acquisition was conceived as a lasting legacy of the show in collaboration with Jammet, who oversaw his mother’s estate until his death in 2017. “He was very public spirited,” Winner says, leaving instructions for the estate to be dispersed between various UK public collections. The Sainsbury Centre was chosen in part to commemorate Frink’s connection to East Anglia—she was born in Thurlow, Suffolk—while the archive was bequeathed to the Dorset History Centre, near her former home and studio at Woolland. The studio building was bought and restored for public display by Messums Wiltshire gallery and arts centre, which is planning an exhibition later this year.

Winner believes the acquisitions, which at the Sainsbury Centre join a strong collection of sculptures dating back to antiquity, will reinforce the achievements of an artist who was at risk of being forgotten. “Thankfully, we’re in a period now where public collections are looking again at artists who were overlooked because of gender, and Frink is in that category,” he says. “If works aren’t shown they disappear. This acquisition is a way to [safeguard against] that. After Barbara Hepworth, it’s Frink.”