After saving it from rack and ruin last year, Messums Wiltshire is to reconstruct the studio of the British sculptor Elisabeth Frink within its 13th-century tithe barn near the town of Tisbury.

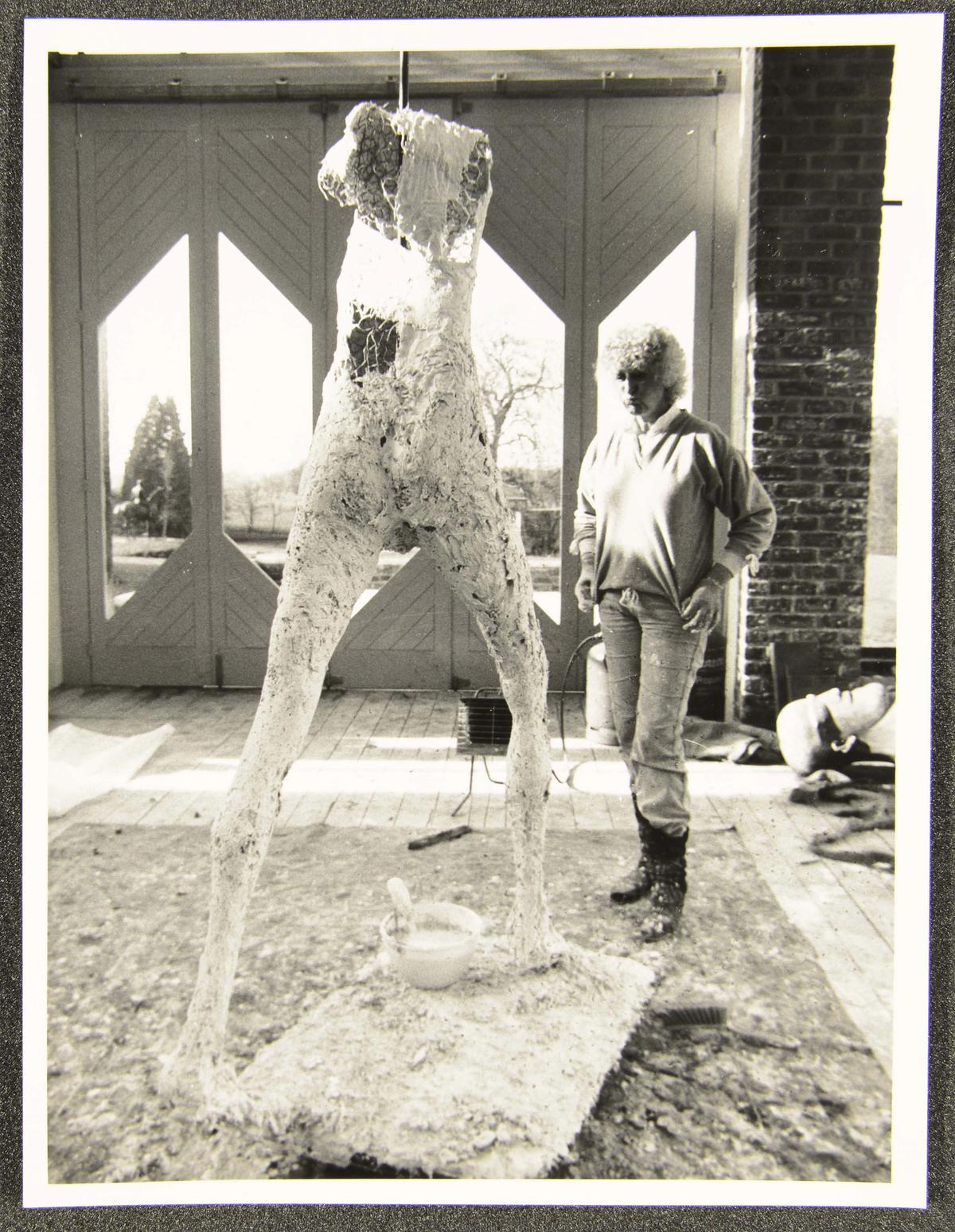

The studio, which has cost a total of £100,000 to buy and restore, will form the exhibition space for A Place Apart—Saving Elisabeth Frink’s Studio (25 April to 28 June), which will feature archival photographs of Frink at work in the studio alongside some of her original plasters, tools and objects all salvaged from her former home at Woolland in Dorset, where Frink lived from 1977 until her death in 1993. Central to the exhibition is a collection of photographs by Ian Chapman, titled White Out of Dark—Saving Frink’s plasters, a record of recovering over 80 original plasters that had been removed from her studio and held in storage between 2017 and 2019.

“I bought the studio because it would otherwise have been lost," says Johnny Messum of his decision to buy the building. "Where and how things are made is a helpful way to better understand a work of art and I particularly like Frink’s work.” The show takes its title from a quote by Frink: “I could not work without a place where I am able to shut myself off...This is the place where I work, I have to keep it apart from everything else.”

Messums has employed the architects Stiff + Trevillion to resurrect the studio, which narrowly fits under the rafters of the cavernous barn, and the gallery plans a programme, dubbed Dialogues, of film screenings, talks, panel discussions, performance and an architectural installation, all exploring the idea of studios and creative spaces.

Frink's studio in its original setting at her Dorset home © Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England

The building will also act as a recording studio as, in collaboration with Dorset History Centre, Messums plans to create a sound archive of those who knew Frink talking about their memories of her.

Annette Ratuszniak, the former curator of the Elisabeth Frink Estate and Archive, writes in the catalogue introduction that after Frink’s son,Lin Jammet, sold Woolland, and the works of art, archive papers, studio contents and chattels went off to storage. But the studio, left in Woolland’s grounds, gradually fell into disrepair.

In 2017, dying of cancer, Jammet said he wished that his mother’s works and archive be given to the nation. “By the autumn of 2019, his wishes were fulfilled,” Ratuszniak says. “The art-store and warehouse had been unpacked and assessed. Museums and galleries across England, Scotland and Northern Ireland became beneficiaries of Frink artworks, archive material, original plasters and studio contents. Now, for the first time, there is the opportunity to see the scale and breadth of her work.”