Without knowing it, or certainly asking for it, we have all become part of a giant social science experiment: can digital platforms offer a satisfactory alternative to experiencing art in the real world? Museums have created points of access to collection databases—some more easily navigable than others—allowing online visitors to look at and learn about specific objects of interest, as well as read blog postings from curators about current exhibitions or about pieces in the permanent collection and follow the institution on social media platforms, using the online world and virtual reality technology to replace or reproduce the feeling of viewing art and other objects in person. This is a process that has been developing at US museums for 20 years, although it has taken on greater significance as the Covid-19 outbreak has closed these institutions to the public for an indefinite period of time.

Michael Neault, the executive creative director for experience design at the Art Institute of Chicago, says that the museum is in the process of “launching a new interactive feature for online users of highly visual narratives about objects in the collection. We will be releasing several of these each week over the coming weeks.” These features will be two to three minutes in length and include 360-degree photography. One of the first of these focuses on El Greco’s 1577-79 painting The Assumption of the Virgin, a featured work in the museum’s El Greco: Ambition and Defiance exhibition that opened on 7 March and was to continue until 21 June, but is now in limbo as the institution is closed to the public.

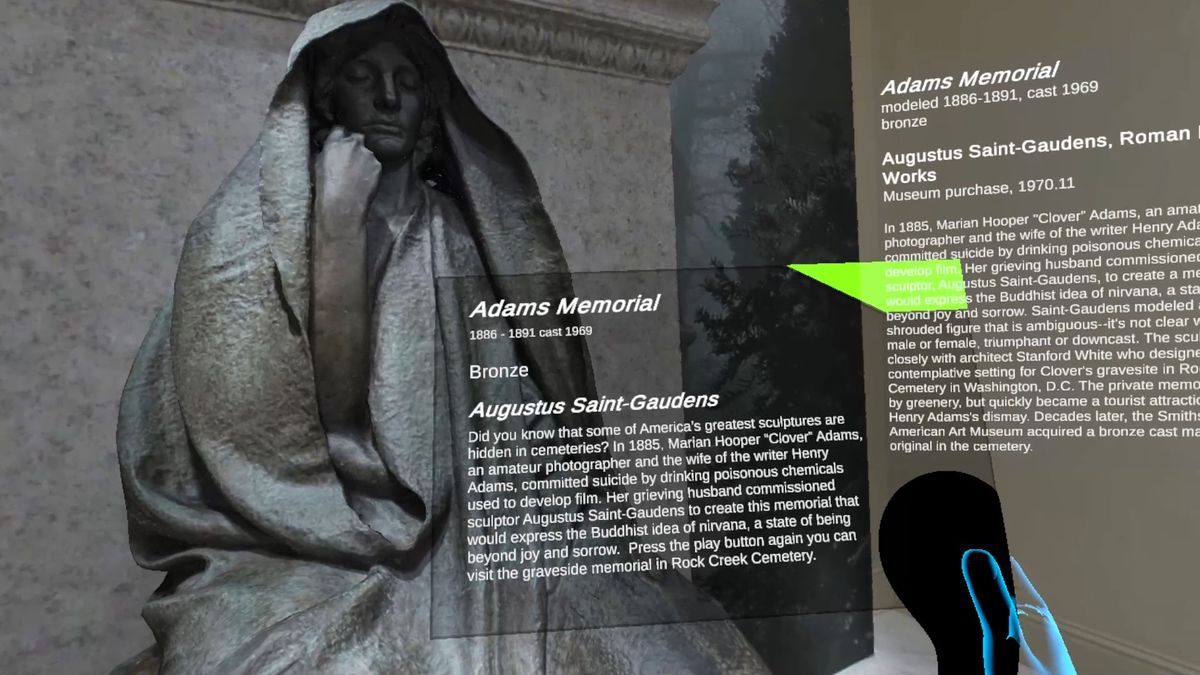

The Smithsonian Museum of American Art has created several digital tours of its the facility, from a standalone exhibition that can be viewed in 360-degrees via an app, to a fully immersive virtual reality experience, that includes art historical information on the works in the collection. And the Salvador Dalí Museum in St Petersburg, Florida, which is currently closed, offers a sometimes dizzying virtual tour of the entire museum, including the bookstore, exterior, fascinating staircase and the art in the collection, which is kept in a hermetically sealable third floor gallery in case of hurricane flooding.

But the experience of museums with their online platforms has been mixed. Neault says that when the Art Institute had a relaunch of its website in 2019, which included making more than 50,000 works in the permanent collection whose images were in the public domain available for free downloading, “there was a massive increase” in traffic. Most visitors to the website were not seeking to copy images of artworks, however, but largely looking for information about admissions prices, hours, if there is a food service and what is on display.

“Museum databases, historically, have been used by researchers, scholars and students who are looking up specific information,” says Susie Wilkening, a museum consultant in Seattle, Washington. “The general public has not made much use of them so far—but that may change.”

Paul Orselli, a museum consultant in Baldwin, New York, notes that museums “are not just about the stuff they have on display. They are meant to be social gathering places,” adding that the aim of many of the accessible databases and virtual reality systems is to “recreate that feeling of being in this place along with other people. People want to be there.”