Kettle's Yard in Cambridge is one of Britain’s best loved art spaces. The intimate rooms of these four knocked-through cottages have been meticulously preserved as a shrine to the Modernist taste of the former Tate curator Howard Stanley "Jim" Ede, who lived here with his wife Helen between 1957 and 1972. Yet while Kettle's Yard is always associated with the aesthetic of Jim Ede, rarely does Helen get a mention. The unique look of the place is often credited to Ede’s determination to create “a living environment” for his collection. Works by his artist friends such as Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Alfred Wallis, Henry Moore, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska fill the space, all carefully arranged in the studiedly domestic setting amongst furniture, glass and ceramics and quirky arrangements of shells, stones and found objects.

The only room outside Ede’s curatorial jurisdiction was his wife’s small bedroom, which was also strictly off-limits to the guests attending the open house afternoons that were hosted by her husband every day during university term time. Now this bedroom sanctuary and its enigmatic occupant have been brought into the foreground by the artist Linder, whose first UK survey fills every part of Kettle's Yard with sights, smells and sounds under the umbrella title of "Linderism".

Channelling and championing invisible female figures from the past is an important part of Linder’s practice, whether they're the forgotten porn stars in her photomontages or elaborate performances revolving around Barbara Hepworth and the Surrealist artist Ithell Colquhoun. Linder’s film The Bower of Bliss (2018) made at the stately home Chatsworth House invoked the presence of Mary Queen of Scots, and at Kettle's Yard Helen Ede is the latest protagonist in this quest to give new power to women who have been overlooked or underrated.

A Naum Gabo sculpture is shown alongside Linder's sculptures Courtesy of Louisa Buck

“Helen’s room feels to me very much like a bower of bliss, a pleasurable and safe place for women,” says Linder, adding, “I wanted to amplify that pleasure.” To this end, all manner of special sensory interventions have been made into this small, sparse room, which previously had no trace of Helen. A cast-glass bowl full of potpourri based on Jim Ede’s own special recipe perfumes the air and in a glass-fronted cupboard a Naum Gabo sculpture keeps odd company with Linder’s sculptures of gloves and shoes sprouting curling cascades of artificial hair. These are all named after hairy female saints and martyrs, including Saint Uncumber—who is, appropriately, the patron saint of difficult marriages.

Especially intriguing for Linder was the discovery of a small hatch set into the room's skirting board at floor level. Connecting directly down to Jim’s separate bedroom below, it was apparently used by Mrs Ede to communicate with her husband. This secret cavity now contains a specially commissioned sound work composed by Linder’s son Maxwell Sterling. Set to a string accompaniment, the piece features women’s voices gently intoning the names for female sexual organs in a variety of languages ranging from Urdu and Turkish to French and Old English. "The Bower of Bliss is also a euphemism for the womb, the birthplace, the vagina," Linder is keen to point out. The artist was also very happy to discover that another Old English term for female genitalia is "Kettle". This soothingly subversive sound work was also performed live by Sterling downstairs at Kettle’s Yard house on the opening night of the exhibition.

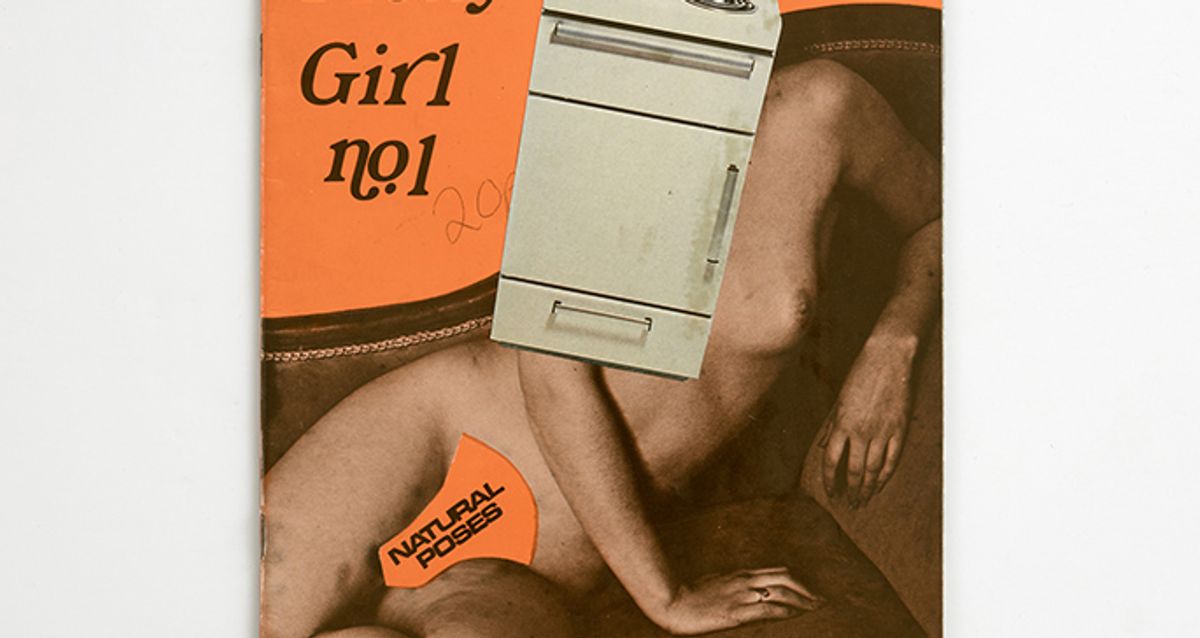

Linder’s trademark photomontages, which she has been making since she was an art student in the late 1970s, are comprehensively represented in her survey in Kettle’s Yard’s new Jamie Foberts-designed temporary exhibition spaces. But one series has also made its way on to the walls of Helen’s bedroom. Here, cavorting models from 1970s Vogue are fused with and also pinned down by images of Modernist furniture and household goods cut out of other magazines from the same era. These fixtures and furnishings deliberately recall the stacked forms and space play of Barbara Hepworth, another female presence in the Kettle's Yard house. The timing is another crucial factor. “Barbara Hepworth broke her thighbone in 1970 and so her mobility was constricted. Fashion photographers show women striding out in the world, but the adverts that tether the women to the home were telling a very different narrative,” Linder says.

The Helen-ified giftshop at Kettle's Yard Courtesy of Louisa Buck

Whether saints or sculptors, the channelling of historical women in a richly sensory environment is one of the many means used by Linder to revive the absent Helen. However, the most public way in which the late Mrs Ede is re-instated as the mistress of Kettle's Yard is in the gallery gift shop. Here, Linder has created an entire House of Helen line of products, including bath salts, makeup mirrors and a range of jewellery based on the letter "H" on the hot tap in her bathroom sink. More subversively Linder has staged a takeover of the Kettle's Yard website, where Helen’s name now comprehensively replaces that of Jim’s and the pronoun “her” takes the place of "his". Then there’s a new limited edition print which features a 1920s portrait of Helen but with her face entirely obscured by a cluster of red roses. One feels that Mrs Ede would have heartily approved.

Linderism, Kettle's Yard, until 26 April