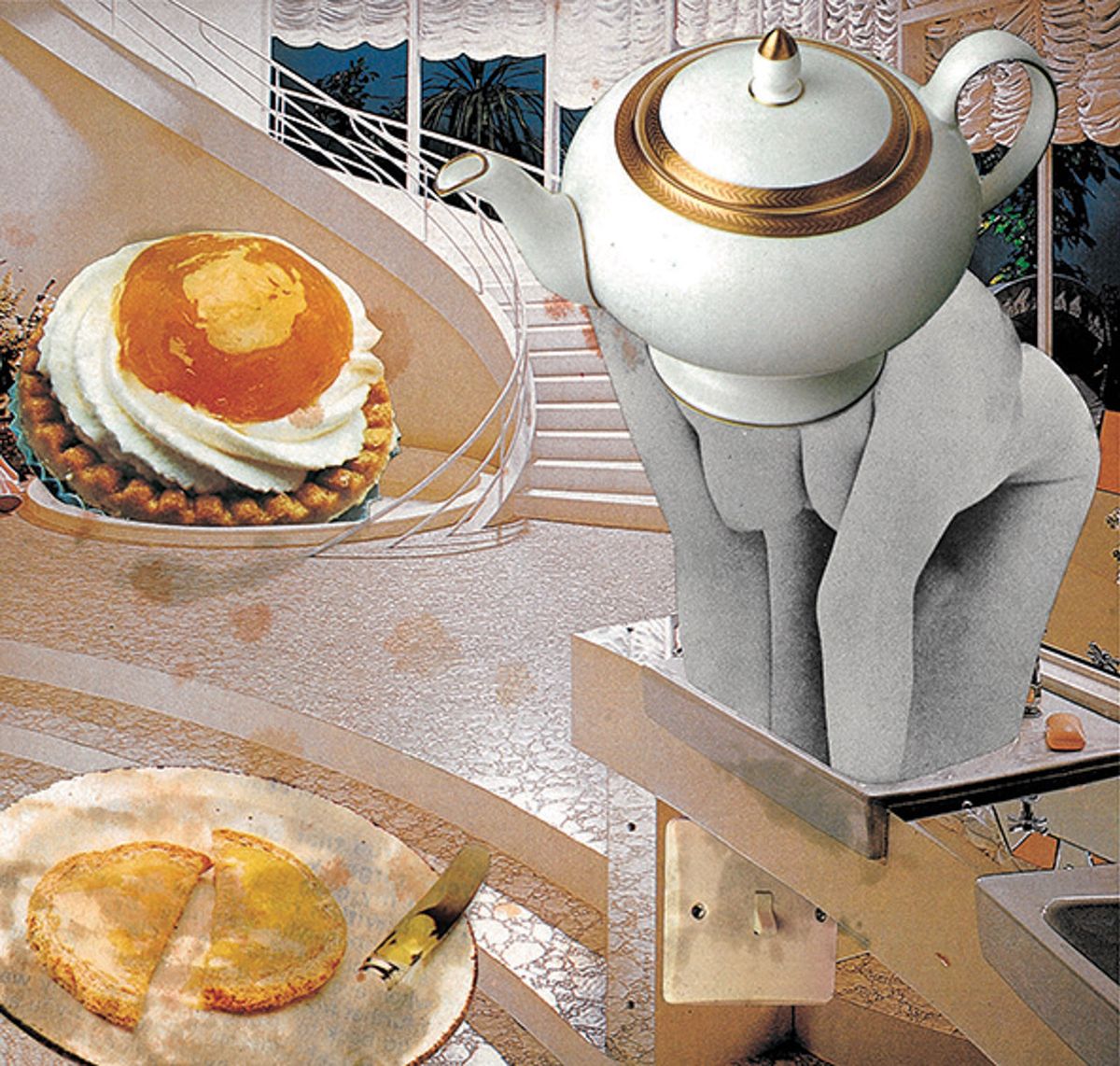

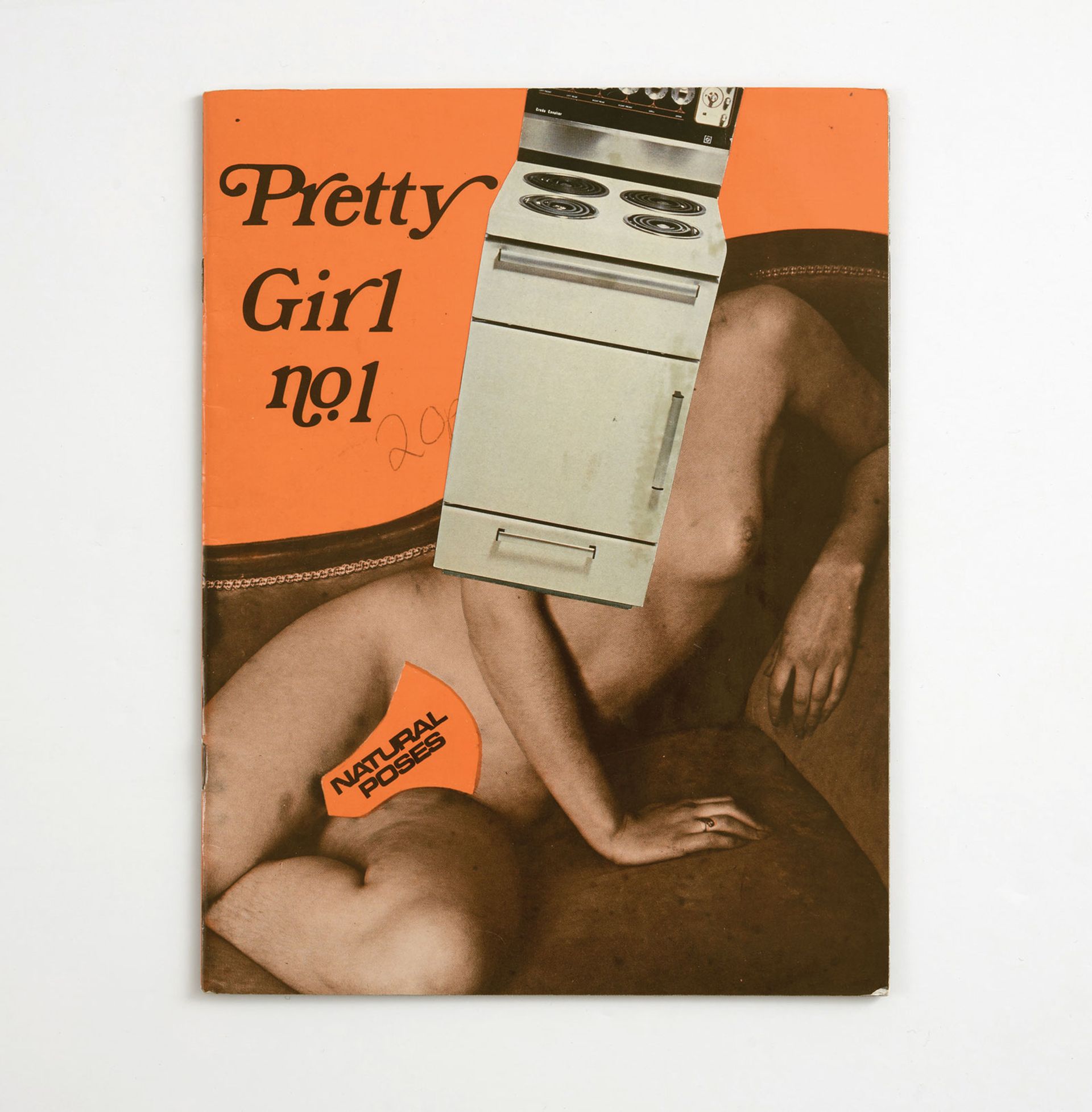

A nude woman leans forward seductively with a teapot for a head, another lingerie-clad figure stretches behind a cleaning appliance, while an oven covers the face of a naked model reclining on the cover of Pretty Girl erotica magazine. This provocative combination of female form and inanimate object is the early 1970s work of photomontage master Linder. Along with five decades of sculpture, photography and several new commissions, these photocollages appear in the retrospective, Linderism, which opens this month at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge.

“I think Linder approaches the sites and archives she engages with in a similar way as she does print media,” says the exhibition’s curator Amy Tobin. The artist’s interventions in the museum will include special staff uniforms and café menu, in a manner not too dissimilar to the precise splicing and sticking of collage making. “There are latent stories, untold, or parallel histories, excluded in the construction of any space, or image,” Tobin says. “Linder was certainly interested in these aspects of Kettle’s Yard, particularly in Helen Ede’s absence from the space.”

Helen Ede was the wife of Jim Ede, who was a curator at the Tate before they made their home at Kettle’s Yard, playing host to tours of their private art collection, which has been kept more or less how it was when they moved out in the early 1970s after leaving the house to the University of Cambridge. Despite both living in the space for 15 years, Helen’s presence is a lot more elusive—her bedroom was the only room not to be preserved when the University originally took over the house.

Linder's Pretty Girl No.1 (1977) © Linder Sterling

Intrigued by a hatch the Edes used to converse between their bedrooms, Linder has developed her own channel of communication with a sound work (produced with her son Maxwell Sterling) to haunt Helen’s room and address her silence and erasure. Linder has also created a new photomontage using a photographic portrait of Helen that “will be available as part of a series of new “products” sold in the Kettle’s Yard shop under the fictional brand House of Helen”, explains Tobin. “Borrowing the language of a fashion house is a means to playfully state Helen’s claim on Kettle’s Yard.”

Linderism is an in-depth appraisal of both Linder’s practice and the history of Kettle’s Yard. “It is always important to reflect on what we think we know, particularly at Kettle’s Yard, which, with its static hang, is a sealed-off historical space,” Tobin says. “Linder’s interventions respond to current cultural circumstances where obscured lives are becoming newly visible, but Linder also reminds us of the terms of its erasure in the first place. Nothing can be totally recovered.”

• Linderism, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, 15 February-26 April