There was little by way of the Modern at Phillips’s subdued sale in London last night where almost 60% of works were created after 2000. The auction, which fielded just four lots over £1m, failed to meet its low estimate, making just £17.5m (£20.7m with fees)—down 44% on 2019.

In recent years, Phillips’s roster has grown to incorporate more early- and mid-20th-century material, but difficulties consigning masterpieces has also dogged Sotheby's and Christie's this week, leading the firms to promote newer pieces that might usually be more at home in a day sale.

Indeed, you could smell the paint drying on the first two lots at Phillips, although this only seemed to spur on bidding. Appetite was voracious for the Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo, who went from auction debut to top ten in a matter of minutes. Driven up by an online bidder from Hong Kong, The Lemon Bathing Suit (2019), a gestural portrait of a black woman floating on a lilo in a pool, eventually went on the phone for £550,000 (£675,000 with fees), more than ten times the high estimate.

As Bloomberg first reported, the painting was consigned by the US entrepreneur and art adviser Stefan Simchowitz, much to the dismay of the artist. Less than three months ago, Boafo’s canvases were being sold at Art Basel in Miami Beach for between $30,000 and $45,000.

When asked about such flipping practices, Phillips’s chief executive Ed Dolman said after the sale: “We try hard not to ride the wave when it comes to pushing the market.” He noted that the auction house’s record last night for rising star Tschabalala Self’s Princess (2017), which fetched £350,000 (£435,000 with fees), comes on the heels of a steady growth in her prices at auction.

However, without continued nurturing, such peaks can become temporary fads. The London dealer Omer Tiroche, who himself put in an “opportunistic” bid, as he put it, on a work by Julie Curtiss, another of this week’s millennial high performers, says fewer new collections are being built with long-term vision and direction.

“Every other speculator, or even new collector, has a list of 10-15 names and is only looking for the best possible examples by those hot, young artists. It’s so boring,” he says. “For flippers buying these artists, it’s a bid to make a quick buck, and for actual collectors it’s a status symbol of being able to boast that they were high enough on the galleries’ waiting lists to be awarded the privilege of buying them primary.”

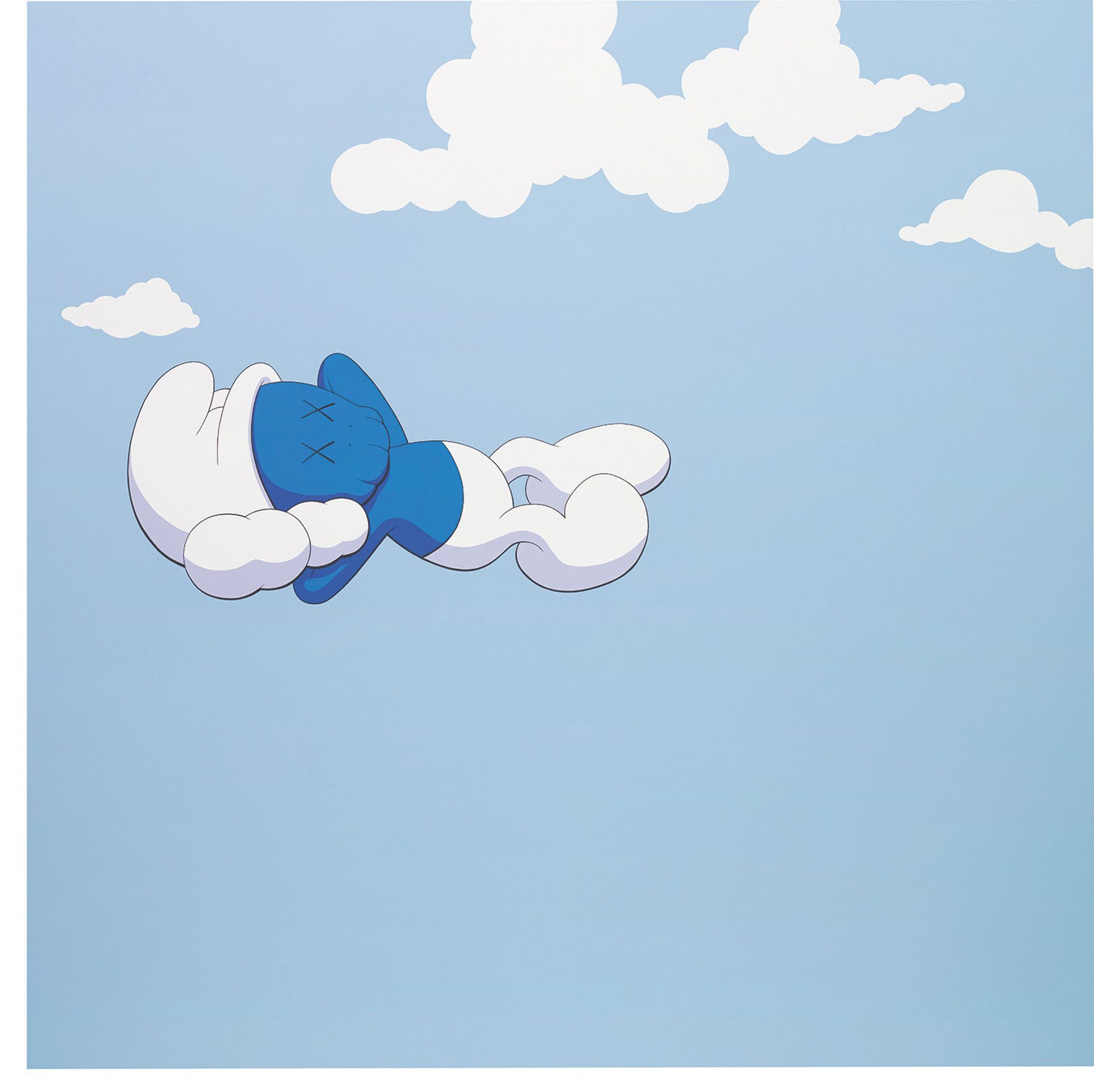

KAWS, Far Away Friends (2009) Courtesy of Phillips

One artist whose market appears to be fading as fast as it exploded is KAWS. His 2014 wooden sculpture, Final Days (est £700,000-£900,000), was one of four lots withdrawn right before the sale due to a lack of interest. Another grey canvas, On Time (2011) failed to sell at £300,000-£400,000, while a vacuous powder blue painting of a floating Smurf, guaranteed by a third party, sold below estimate for £750,00 (£900,000 with fees).

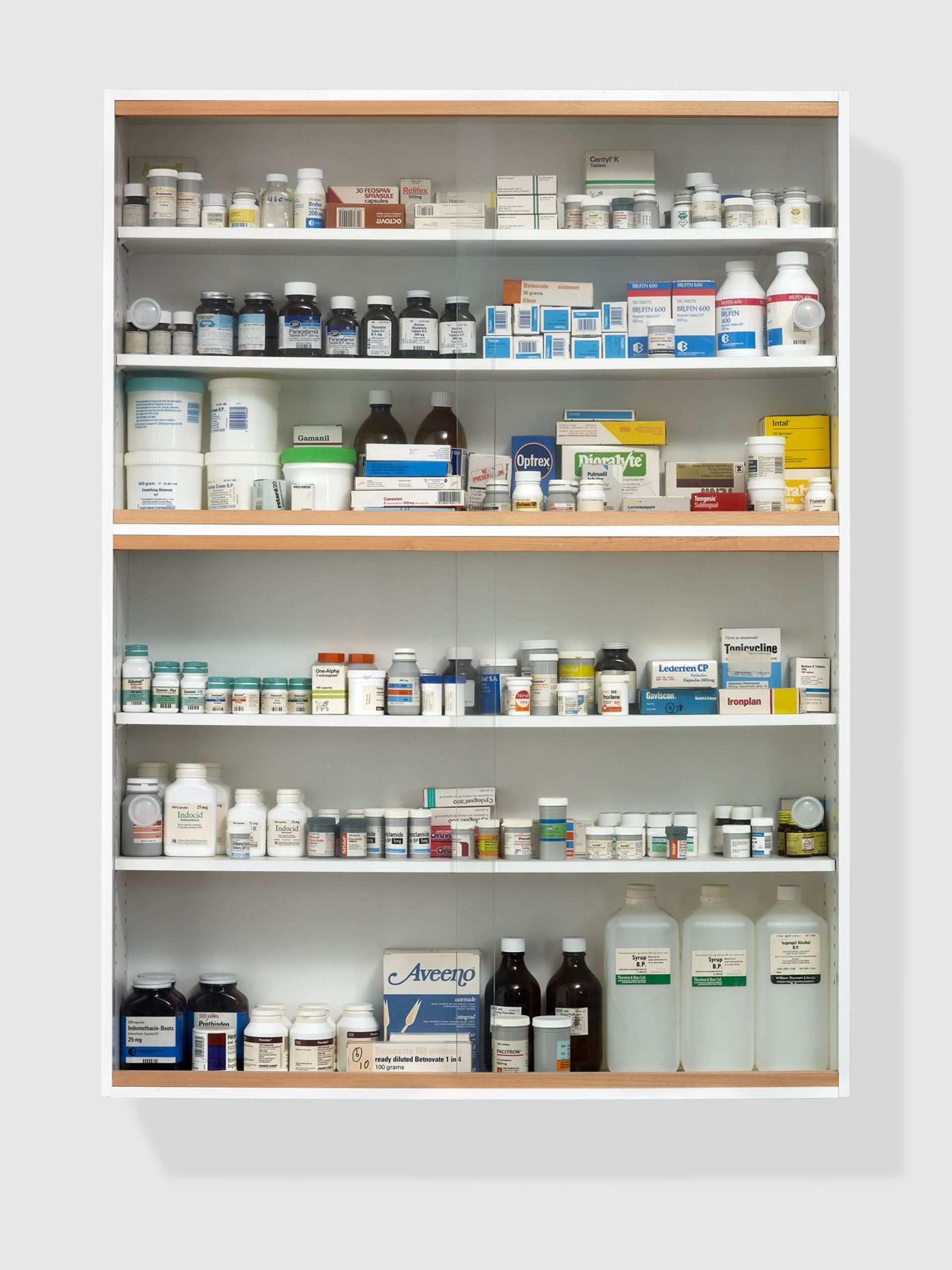

A masterclass in art history, albeit chiefly from the 1990s, came courtesy of the collection of the London bond salesman Robert Tibbles, who amassed around 30 works by the Young British Artists between 1988 and 2004 and was one of the first to buy a work by Damien Hirst.

In 1989, for a mere £600, Tibbles bought Hirst’s Bodies, one of the first medicine cabinets the artist created for his degree show at Goldsmiths College that year. Last night, it sold for its low estimate of £1.2m (£1.4m with fees). Hirst revealed before the sale that he bought all the elements from B&Q and collected the medicine bottles and boxes from his local hospital in Greenwich. “It was before I had assistants and so I made it myself in my kitchen,” Hirst said on Instagram.

Damien Hirst, Bodies (1989) Courtesy of Phillips

Four works by Hirst were guaranteed by a third party, including the medicine cabinet and an early and rare hand-painted spot painting from 1994, which achieved £1.05m (£1.3m with fees; est £900,000-£1.2m). A further four lots were backed by third parties.

Hirst said he was not at all sad for Tibbles to sell his collection, which brought in £3.8m against a £2.8m low estimate. “He believed in me when no one did. Not many people bought my work in those days and the ones that did, sold it pretty quickly,” the artist said.

Since those early days, Hirst’s work has gone supersized. His latest commission, according to Instagram, is a chapel in the south of France, at the Chateau Lacoste, for which he is creating a spire consisting of a huge bronze arm “pointing to god”.

With the evening and day sales expected to be down by almost a quarter this week, the auction houses will be praying for a miracle when it comes to consigning for the June season. For now, it seems London is at “low tide”, as Tiroche puts it.

And while many have cited Brexit and the election as making consigning brutally difficult, Tiroche suggests the political instability is being used “as an easy scapegoat”. He says: “British business—both consignors and buyers—accounts for a very small portion of the London auction market. Ultimately, a lot of sellers prefer to consign to New York or even Hong Kong for top notch Western material.”