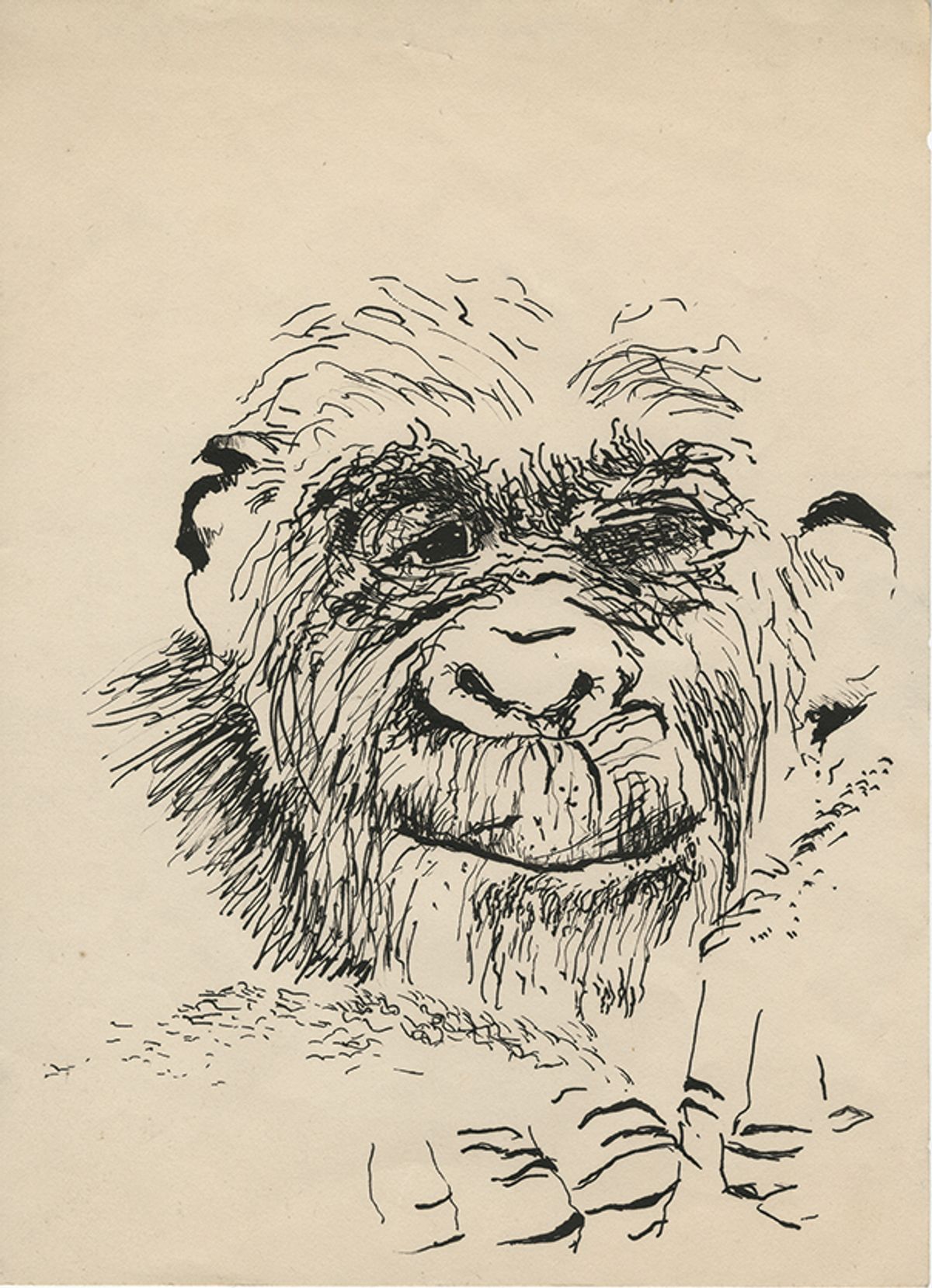

In 1963, while still a high school student in Salt Lake City, Paul McCarthy did an ink drawing of a smiling, wizened chimpanzee. He called it Self-Portrait, and—to his apparent bemusement—it has become the lead image for a retrospective of McCarthy’s drawings at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Co-curated by Aram Moshayedi and Connie Butler, Paul McCarthy: Head Space, Drawings 1963—2019 does a compelling job of tracing through-lines from the 74-year-old artist’s earliest work to his latest gargantuan multi-media productions melding performance, film and installation. “Drawing becomes a way of understanding the breadth and depth of McCarthy’s artistic process,” says Moshayedi. “It grounds almost everything he has made over the past five decades.”

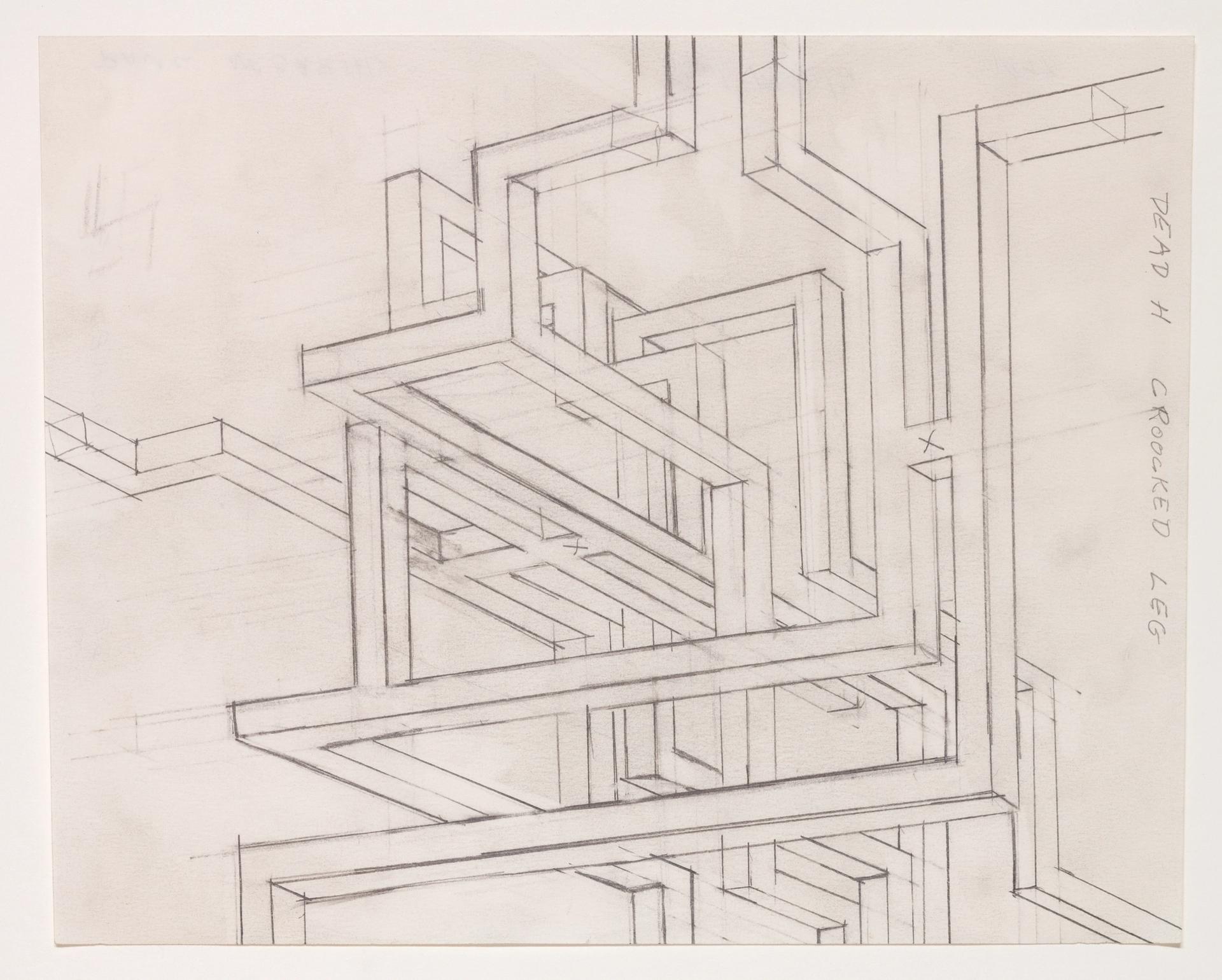

McCarthy's Dead H Crooked Leg Maze (1979) Photo: Fredrik Nilsen: courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Walking through the partly hung exhibition a week before its opening, McCarthy expresses gratified surprise at how prescient many of his early experiments were. “It’s crazy how some of these works became really important later on,” he says, looking at a framed grid of Stoned Blue Drawings (1968–69), made before he gave up drugs in the 1970s. Among grotesque caricatures and abstracted genitalia is a smiling Santa. “How many Santa Clauses did I make?” he muses.

Other works from the 1960s include typed instruction pieces (“Pile dirt on your desk and leave it”), proposals for Minimalist sculptures such as Dead H Drawing (1968) and drawings of mummies from a Salt Lake City museum. Piles, stacks and boxes have all recurred throughout McCarthy’s oeuvre. (Even that chimp reappeared in a 1980 performance, Monkey Man, not in the exhibition.)

Airplane Painting (1965-66), a violent, expressive painting on paper with collaged elements depicting fighter aircraft, is uncannily congruent with the huge drawings from the 2000s that viewers encounter in the final room of the broadly chronological show.

Magazines, too, have long featured in McCarthy’s work. For an animation class at the University of Southern California, McCarthy recalls, “I just tore pages from magazines, put them under a crane camera and filmed them. I would zoom in, I could move the camera, but not move the image.” The project did not go down well at the traditional film school, but in this exhibition the eight framed magazine pages, Film of Desire (1970–71), highlight McCarthy’s ongoing use of appropriation.

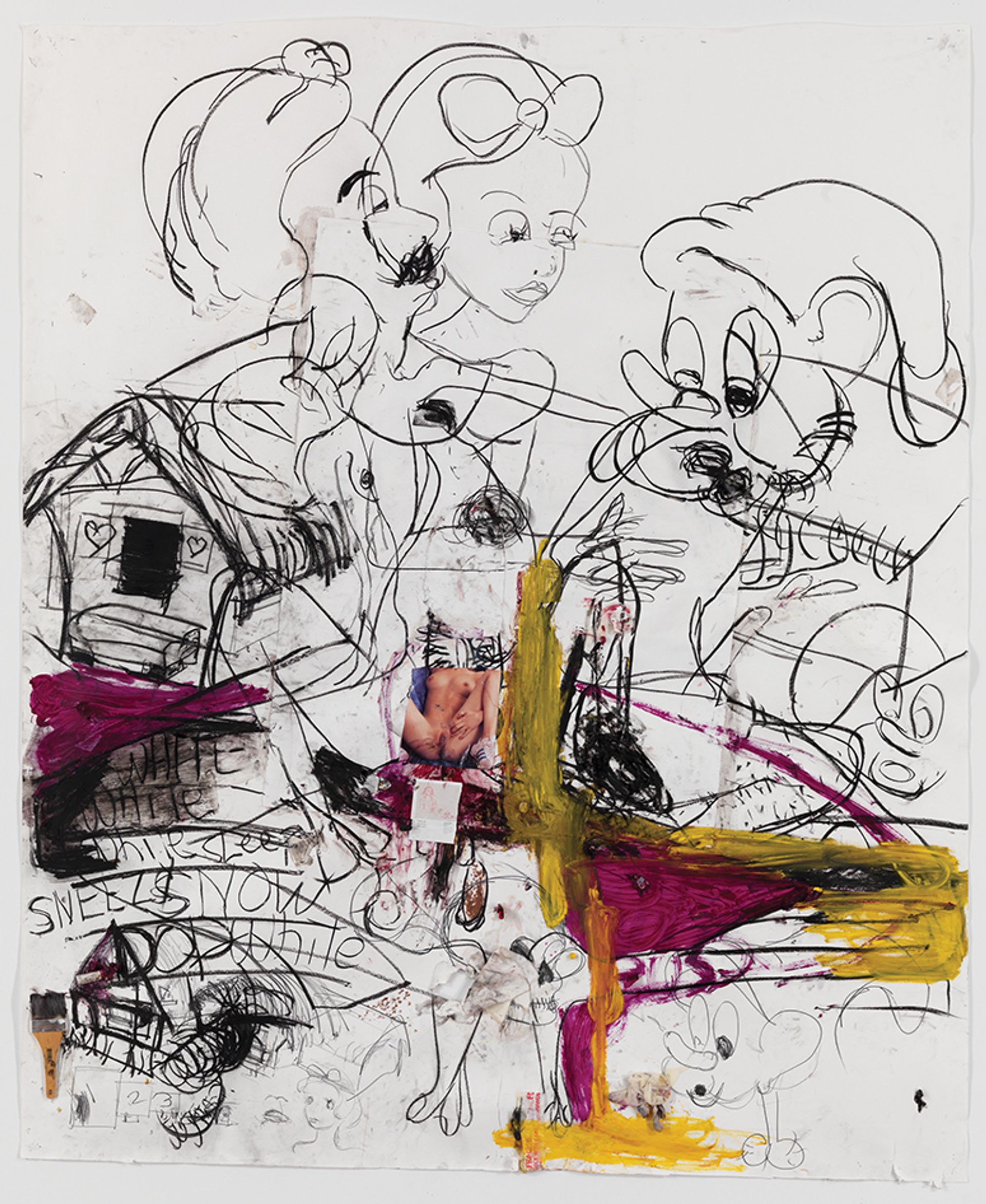

Paul McCarthy, Dopwhite, WS (2009) Hauser & Wirth Collection, Switzerland

Many works from this period have been lost. “Moving around, we just left things all the time. I wasn’t saving work,” he says. And presumably, I suggest, he didn’t have much of a market for his work back then. “I think, before 1991, I sold one work of art!” he answers.

McCarthy’s drawings really took off, in terms of scale and ambition, in the early 1980s. For an exhibition in 1982 at the now-closed Exile Gallery, in downtown Los Angeles, McCarthy redrew five small drawings related to his earlier performance, Sailor’s Meat (1975). He made the new drawings in the gallery, alone, in charcoal on giant pieces of paper up to 22ft high.

Two years later, McCarthy produced another monumentally scaled drawing, Baby World (1984), which combined sometimes frenzied mark-making with cartoonish faces, testicles and vulvas. “They were big enough that I had to be on top of them,” he explains of these large works. “I did them on the ground—kind of like the drawing was an arena.” Up close, it was hard to judge proportions, so the process yielded unpredictable results. For McCarthy, bigger was not necessarily better, however. “I don’t think the scale of these drawings has to do with wanting to dominate a viewer, or dominate a space. It was about wanting to be in something,” he says.

The period was a turning point, as McCarthy began to recognise the performative potential in drawing—even if, at first, his drawing sessions were performed for an audience of only one. By the end of this exhibition, drawing occupies various distinct roles in his process. Frenetic, information-packed storyboards, made in pre-production for projects such as CSSC Coach Stage Stage Coach (2017), hang opposite drawings from White Snow Walt Paul Life Drawing, Drawing Sessions (2013), done on set and in character as “Walt Paul”—a perverted amalgam of Walt Disney and himself—of (and with) McCarthy’s collaborator, the actor Elyse Poppers, who plays “White Snow”. As with so much of McCarthy’s output, it is impossible in these works to discern where persona ends and so-called reality begins.

• Paul McCarthy: Head Space, Drawings 1963-2019, Hammer Museum, until 10 May